Early California Gardens

Contributor

Serendipity keeps on happening by chance, as Yogi Berra might have said. In the course of research for my first book, The Olive in California: history of an immigrant tree, I came across an unpublished manuscript by Harry Butterfield, which forms the core of a new book, from which this article is adapted.

Harry M Butterfield spent his entire professional life in the Agriculture Extension Service of the University of California at Berkeley. He was born in Nebraska in 1887 to a pioneering farm family that moved ever westward. They finally stopped when they reached the Pacific coast and settled in Orange County. He was the second of eleven children. To show how hard things were then, it took him and his next eldest brother two years to complete the last stage of high school. One of them would work and the other attend school. Harry was the first member of his family to go to college.

After a few apprentice years, he joined the university extension service. His task was to be the interface between the science of the academy and the person in the garden. Butterfield wrote numerous pamphlets and lectured widely on the best ways to grow flowers and vegetables. During the Second World War his advice was invaluable, as more and more people turned to growing their own food.

It is not clear when he became interested in the history of California horticulture. It could be said that Butterfield almost created the discipline. He contributed many articles and papers to the literature on pioneer California nurseries and the horticulture of the past. Many scholars value his compilation of the dates that exotic plants were introduced into California. Upon retirement, he pulled all the material together in the form of a manuscript, which he called California’s Gardens of Memory. Butterfield died in 1970 before he could get the book published. In developing a book from his original manuscript, I chose a different title, as “gardens of memory” brought to mind images of cemeteries, which was not at all the focus of the book.

Tustin

Butterfield attended grammar school in Tustin, in Orange County, when he was six. The town had been founded by Columbus Tustin in 1867 on the San Joaquin Rancho of Andres Sepulveda. It had the most beautiful gardens when Butterfield was a boy.

In 1890, Gustav Eisen wrote about how the street car in Tustin “winds its way under shady lanes on either side, bordered by large and graceful pepper trees covered with spice and fragrant blossoms. . . . On one side are old graceful trees with drooping limbs, on the other are well-kept cypress hedges trimmed square or even, or long natural barriers of ever-blooming geraniums [Pelargonium] in numerous varieties, of every favorite shade of color from crimson to palest pink. Over the hedges we look into bluegrass lawns, green and well-kept and exceedingly attractive.”

Butterfield remembered the cypress tree from which switches were cut. He recalled the grevillea (Grevillea robusta), its flowers of golden silk and the seed pods that, in a child’s mind, resembled the outline of an ostrich. There was also a green rose from China which a San Francisco nurseryman exhibited in 1854.

Butterfield wrote: “Once again my thoughts turn back to a boyhood garden on a farm not far from the Santa Ana River near the West End School. I can still picture the fancy-leaved border geranium, [Pelargonium domesticum] ‘Madame Salleron’, and nearby Salvia greggii in the base planting, green foliage contrasted with scarlet flowers. On another farm was a Seven Sisters rose over the doorway. The swaying branches of a weeping willow tree made a soft sound which lulled me to sleep as a child.”

“While I was at Santa Ana High School, I liked to ride into the hills of Santiago Canyon, not far from the home of Mme. Mojeska. Matilija poppies [Romney coulteri] grew there, white faces uplifted, and speckled trout swam in the stream beside me.“

The scene had changed by 1940. The mountain, old Saddle Back, was still there, and Orange County Park lay at the entrance to Santiago Canyon, but the grape vines which had festooned the trees were gone, having lost their water supply from the brook.

The pepper trees still grew in Tustin, El Modina, Orange, and Santa Ana, but some were beginning to show signs of age. The grevilleas, the elm, and the umbrella tree (Genus species) were there just as in his boyhood, yet the former simplicity of the open spaces was lacking.

Modern Tustin, however, has taken good care of its horticultural heritage. In 1997, Carol H Jordan, a staunch member of the historical society, published a small monograph on the landmark street trees of Tustin. The “official “ tree of Tustin is the scarlet-flowering gum (Eucalyptus ficifolia).

Ventura County

Theodosia Burr Shepherd was a frail woman of twenty-eight when she arrived in Ventura-by-the-sea with her husband and children in 1873. Her husband, a lawyer by training, became editor of the Ventura Signal, and Edith, her fourth child, was born there on August 5, 1876.

Because of family difficulties, Theodosia had married Will Shepherd, a good but impractical man, at an early age. The family had no money except for the pittance from the newspaper. It was essential for Theodosia to earn some money herself. Her children needed clothes and some amusements, even if only very meager ones; they also needed books for their education. Feeling rather desperate, she inserted a notice in the “exchange column” of Harper’s Young People offering to exchange pepper tree berries, sea mosses, shells, and pressed California wild flowers in return for fancy work for her children.

Mrs Shepherd always managed to have some sort of flower garden wherever they lived, and even in fly-blown Ventura, achieved considerable renown for her skill. The response to her exchange activities gradually became overwhelming. She pressed all her children into service, making the floral ornaments, and working extremely hard to grow the seeds.

In 1882, she sent a package of California curiosities and several types of flower seeds to Peter Henderson in New York. He wrote to her in return, “I am certain that California before fifty years will be the great seed and bulb-growing country of the world. You have the exact conditions of climate necessary to grow seeds, and I would advise you to at once begin systematically.” (Henderson had opened up commercial horticulture by writing several important textbooks for the public.)

After two years of exchanging seeds and plants, her collection had outgrown her grounds. She coaxed her husband into buying an adjoining two acres. By 1886, she issued her first catalog and then a wholesale catalog the year following. Between then and 1892, she issued three more.

In 1892, before the Sixteenth Fruit Growers Convention, Mrs Shepherd predicted “California will, in the very near future, be the seed and bulb-producing country of the world, and be the great nursery of the world as well.”

Mrs Shepherd planted named selections of petunia (Petunia hybrida grandiflora), such as ‘Prince and Princess of Wurtenburg’ in 1890, and spent much time hybridizing these flowers. One morning, she showed her neighbor, Mrs Gould, how to do this and proposed that she specialize in this flower. The next year, Mrs Gould delivered about twenty flowers to Mrs Shepherd, no two alike and “all perfect in form and color and giants in size.”

A night-blooming cereus (probably Nyctocereus serpentinum) was thirty-five feet high, and the tree begonias were ten feet tall. There were papyrus, cyclamens, bouvardias, and costly novelties. She grew heliotrope (Heliotrope arborescens) along her two-hundred-foot frontage on Main Street; one can only imagine the enticing fragrance that arose from that planting.

Any appraisal of Mrs Shepherd‘s introductions should include begonias, cosmos, California poppies, small geraniums, petunias, heliotrope, and rare succulents. Her catalogs dealt in superlatives, but she was probably justified. No one else had anything close to her selections.

Begonias such as ‘Marjorie Daw’ were probably among her favorites. Of the tall cane begonias, she had ‘Sylvia’ and ‘Dearest Mae’, plus ‘Pink Rubra’ and ‘Rubra Bamboo’. Her single selections of Begonia semperflorens were listed as ‘Sea Shell’, ‘Couldlet’, and ‘Brilliant’. In the Rex group, she grew ‘Silver Cloud’, ‘Amethyst’, and others. Dr Dimmick, of Santa Barbara, supplied her with B. odorata alba, B. edmondsi, and B. evansiana, forerunners of some modern tuberous begonias.

Mrs Shepherd died on September 6, 1906. She will always be remembered for her Ventura gardens. Harry Butterfield’s first recollection of a nursery catalog was one of hers. His father received it from her in about 1900. Her influence on others has been immense.

Marin County

Butterfield was thorough but some sections of his book had less material than did others. One such section was Marin County. Butterfield was travelling and writing about Marin County for some time before the Golden Gate Bridge was built. He and his wife probably took the ferry from the East Bay to Marin. There were far fewer people living in Marin County then; it was still rural and the gardens were grand and spacious. (In preparing the chapter on Marin County, I have been helped by Margaret Kittle Boyd’s charming booklet, Reminiscences of Early Marin County Gardens, pulbished in 1938.)

[sidebar]

Olompali State Park Today

The only casualty of California’s Bear Flag revolt took place at Olompali in 1846—a melancholy piece of history that must be acknowledged. The property, 8,900 acres, presumably still belonged to the Ynitia family at the time.

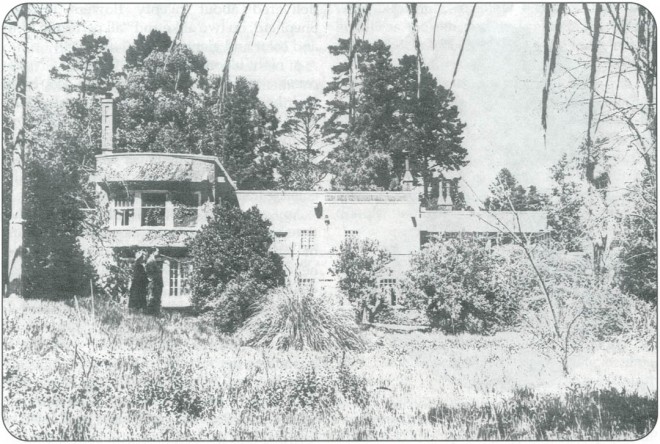

The Burdells moved there in 1862 and added extensively to the old Ynitia Adobe, ending up with a mansion of twenty-six rooms. The accompanying picture shows its rambling style.

After the Burdells died, the house became a Jesuit retreat, part of the University of San Francisco. Though the order was not lavish, the property was reasonably well maintained.

Later, it deteriorated badly. In 1966, the “Grateful Dead” used it as a summer home. Next, a commune called “The Chosen Family” took it over. When that group moved away, Olompali was abandoned to the elements. Part of the house burned down in 1969 and the outbuildings were all in very bad repair. The well-known greenhouse simply disintegrated.

The State of California purchased the estate in 1977 and opened it as a state historical park in 1990. Various plans were promoted to restore the house and garden, but everything came to a halt when it was realized that the original construction contained asbestos. The buildings were covered with protective sheeting, but the budget has not yet permitted definitive removal. No one is allowed to enter the house.

The garden was neglected throughout all of these vicissitudes and rapidly became wild. The park service began the process of restoring the garden and a skeleton can still be seen, but the funds to complete the restoration have not been released.

At present, one devoted ranger, Fred Lew, and some volunteer docents lead tours on Saturdays and Sundays, and dedicated walkers enjoy Olompali’s hiking trails. The park is three miles north of Novato but is only accessible from southbound lanes of Hwy 101, about 2.5 miles south of San Antonio Road exit. For information, phone 415/893-1580.

[/sidebar]

The earliest known residential garden in Marin County was at Olompali Ranch. In 1776, a group of Spaniards was travelling north and stopped at a native rancheria (a small settlement) next to a spring. They camped there for a few days and were made welcome by the native people. In return for this hospitality, the Spaniards taught the natives how to make and build with adobe bricks.

Camillo Ynitia’s father, the last chief of the Olompali tribe, built himself an adobe house using this new skill. This was the first private dwelling built north of San Francisco. Later, Camillo’s son built another house, encompassing the first one. James Black acquired the property and gave it to his daughter upon her marriage to Dr Burdell, a dentist. The original adobe was incorporated in a larger house built by the Burdells when they moved there in 1863.

When the adobe house was torn down years later, the adobe bricks sprouted many plants and unexpected weeds. (The same phenomenon was noted in several places, such as Lompoc and Napa.) The Olompali bricks produced “wild” oats, filaree grass, and burr clover. Alice Eastwood, curator of the Herbarium at the California Academy of Sciences, believed that the oats had come with a European immigrant, since oats were not indigenous to California.

Mrs Burdell laid out a magnificent garden. She understood perspective, grading extensively in front of the house with long graceful terraces leading down to the bay. From their wedding trip to Japan, she brought back numerous Asian plants for her garden. She did not copy Japanese garden design, but stuck to the usual plans of the period. A formal, central bed had brick paths radiating out from it, ending in a larger circular bed, making a giant “wheel.”

The plantings, however, were completely unconventional for the time. Japanese maples, magnolias, oleanders, and camellias survived until the 1930s, when Margaret Boyd was writing. The avenue approaching from the road consisted of handsome eucalyptus and pines, with amaryllis in the understory. In the center of the round flowerbed, a tall spiral palm was dominant. Next to the front entrance of the house, there were four additional tall palms.

Margaret Boyd drew her reader’s attention to two large specimen trees in the garden. One was an old oak (Quercus) with a cross that had been carved in its bark to commemorate the only person to die in the Bear Flag revolt of 18XX. The other was a redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), grown from a seed found in the crop of a quail killed at Fort Ross on the Sonoma coast. Another handsome feature of this garden was a rich hedge of pomegranate (Punica granatum).

While Mrs Burdell had the resources to make her garden unusual, the rest of the ranch gardens from that period were in much the same style: a long avenue of cypress with eucalyptus and a wide circular bed with a solitary palm in its center. Almost nothing of these gardens remained at the time Boyd was writing. Occasionally, a few roses could be seen, but almost all the old orchards had disappeared. Once in a while, Boyd found an isolated, misshapen old pear or apple tree, without any connection to a house.

Mrs Boyd was writing almost seventy years ago. Olompali Ranch is now a state park in Novato and close to the Sonoma County line. The gardens have fallen into decline but there is talk of reviving them.

Gardeners abounded, but the best people did not employ just any gardener. Gardeners were not interchangeable in the way a housemaid might be. Only cooks had the same latitude. Gardeners (and cooks) might be surly and ornery, but the employer bit his/her tongue and tolerated them for the sake of their reputation in the social and horticultural stakes. There was, for instance, a not-so-subtle rivalry among all these society ladies as to who had the best roses, the greatest variety of rhododendrons, the earliest strawberries, and most abundant peaches.

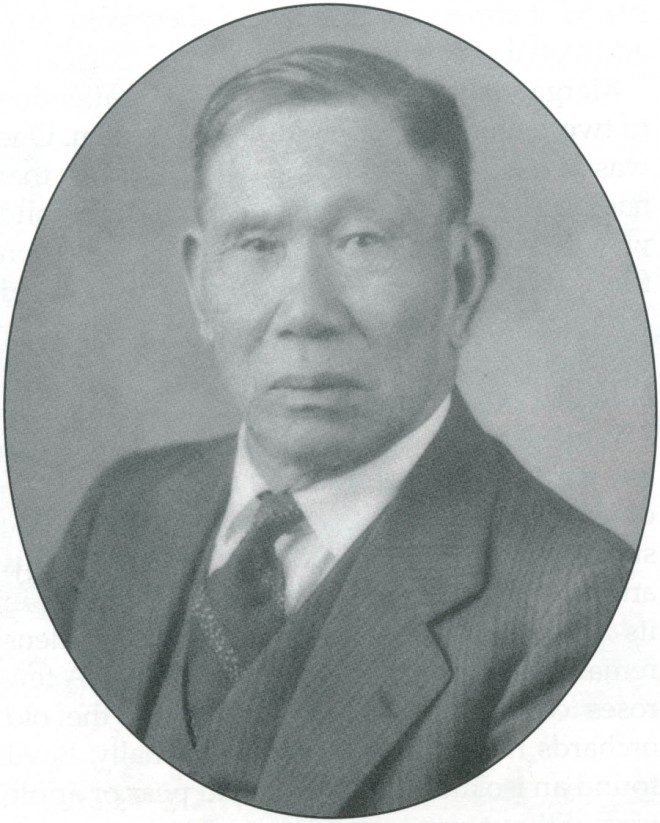

One of the more colorful characters among the gardeners of the period was Ah Sing, Louise Boyd’s Chinese gardener at Falkirk. He was a virtual tyrant for fifty years, from 1885 to 1935, allowing no one else to make any decisions about what was grown and how—not even his employer. Only gardeners could tell their employer home truths and get away with it. In an age when servants were invisible and anonymous, Ah Sing stood out. As a thank you upon his retirement, Louise Boyd arranged through her friends, the Dollars, owners of a shipping line, for Ah Sing to sail back to China, so that he could live his remaining years in his native land, according to the demands of his religion. Her garden was never the same.

In the town of Ross was a garden that Margaret Boyd believed was the finest in Marin county at that time. Albert Dibblee bought a large part of the older Ross estate in 1870, and built a typical “New York Hudson River” style of house with a fourteen-foot veranda across the entire front. Roses abounded: Lady Banks (Rosa banksiae) covered two sides of the house and R. ‘Marechal Niel’ grew along its southern exposure. Dibblee had moved to Marin from New York, and named his new home “Fernhill.” It is now the site of the private Branson School.

Trees dotted the lawns and there were immense beds of “old fashioned” flowers: asters, cannas, wall flowers, chrysanthemums, marigold, and stocks. Planted in the 1870s and 1880s, these flowers are timeless and continue to be grown and cherished today.

Dibblee was passionate about trees. He planted many of them in the streets of Ross. Some survived until the mid-twentieth century. In his own garden, there were dozens of trees that had been obtained for him in China, Korea, and Japan by his friend Admiral Shufeldt. The admiral had “opened” Korea and was the first American ambassador there under President Grant. Other trees and plants had been sent from nurseries in New York and various parts of the United States.

The inventory of the trees and plants in his garden is long. It included American elms (Ulmus americana), linden (Tilia species), horsechestnuts (Aesculus hippocastanea), hickory (Carya species), and an astonishingly tall tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera). His daughter, Nellie, had visited Yosemite and, in keeping with the custom of young ladies at that time, had brought back a handful of sequoia seed wrapped in her handkerchief. One of these seeds grew into an large and healthy Sierran redwood (Sequoia gigantea).

It is interesting that Dibblee planting his trees as individual specimens or small groups in his lawn. He may have seen this is his travels, perhaps to England, where many estates were influenced by the work of the eighteenth century landscape designer “Capability” Brown; or he may have, consciously or unconsciously, been reflecting the appearance of Marin county’s wild landscape with its oak savannas.

Dibblee also planted an orchard. The trees were still actively producing fruit fifty years later. He had ‘Bellflower’, ‘Newtown pippin’, and little ‘Christmas’ apples, plus pears, cherries, quince, walnut, pomegranate, persimmons, figs, and olives. Like Louise Boyd and other landowners, Dibblee employed several Chinese gardeners.

After Albert Dibblee’s death in 1895, his widow built a new house on Upper Road in Ross. It was intended for her daughter one day, but the daughter, an artist, preferred to live more simply. Eventually Dibblee’s son Benjamin inherited his father’s house.

In its heyday, the garden had occupied seven acres, densely filled with rare plants. There were many formal beds and elegant shrubs. The camellia walk, with camellias on both sides and ending at a seat, and the “little garden” outside the dining room were both designed by the Olmsted Brothers of Massachusetts. The house and garden looked toward Mount Tamalpais—an incomparable “borrowed landscape.”

Benjamin Dibblee was an inveterate hands-on gardener, vigorously digging, fertilizing and planting together with the hired staff. He could be touchy about his treasures. One relative coveted some of his exceptional blue pansies, but he did not want to share them with her. She was resourceful, cajoling the gardener in the greenhouse. When he found out, he was said to be extremely irate. Thomas Dibblee’s sister, verified this story. She had heard it from the culprit, Mrs Harrison Dibblee, her grandmother.

Adapted from the forthcoming book, Tangible Memories: Californians and their gardens 1800 –1950, by Judith M Taylor MD and the late Harry M Butterfield (San Francisco, California, Hort Historia Press), soon to be available from Xlibris.com.

[sidebar]

References

Boyd, Margaret Kittle. 1934. Reminiscences of Early Marin County Gardens. San Francisco, California: San Francisco Garden Club. (Re-issued by the Marin County Historical society, no date)

Duflot de Mofras,M. 1844. Exploration du territoire de l’Oregon, des Californies et de la mer Vermeille executée pendant les années 1840, 1841 et 1842. Paris: A Bertrand.

[/sidebar]

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses