Protecting Invertebrates from Pesticides with Garden Futurist Aaron Anderson

Contributor

- Topics: Garden Futurist

Winter 2024

Listen to the podcast here.

Invertebrates do so many important things. But beyond the benefits they provide to ecosystems, they’re fascinating creatures. When you look at them closely, bees are all sorts of metallic colors. There is a beautiful diversity of butterflies. Parasitoid wasps have amazing antenna that are branching in different directions. A lot of us just aren’t aware of them when we’re out in a garden or going for a walk, because so many of them are so small. The more people appreciate how cool they are and how important they are, hopefully the more interested they’ll be in conserving them and protecting them.

Aaron Anderson, Pesticide Program Specialist, Towns and Cities Lead, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

This episode was sponsored by:

Sarah Beck: You’re listening to Garden Futurist. I’m Sarah Beck, here with Adrienne St. Clair. Hi, Adrienne.

Adrienne St. Clair: Hi, Sarah.

Sarah Beck: I’m really glad that this conversation, which I think is a need-to-know conversation, was with Aaron Anderson, who is about the most fun person to talk to.

Adrienne St. Clair: He can balance the tragic news with the interest and beauty and amazement all at the same time.

Sarah Beck: Totally. It’s really cool to have an opportunity to talk to Aaron, because the work he’s doing is so specifically urban.

He’s just using a perspective on the garden experience, it’s so specialized. It’s really great for us to get to hear this angle. I think very few of us as horticulture people have as broad a knowledge of the invertebrates that are garden related.

Adrienne St. Clair: This is one of the things I enjoy most about this podcast is that there’s so many aspects of horticulture that I am interested in, but I can’t be the official person to talk to. I can’t be the professional on this one. And so here’s another aspect of something that’s so fascinating, but takes so much time to fully understand.

Sarah Beck: What was your prior knowledge on some of this pesticide toxicity question? I’m curious what your baseline on this was.

Adrienne St. Clair: It’s not something I research on my own, so I haven’t done a lot of the reading that makes me confident in talking about it.

So what I hear are just these snippets that make me concerned about learning more. I’ll hear snippets about glyphosate killing off soil bacteria and thinking about soil health.

Aaron talks about the microbes in the gut flora of insects and affecting gut flora and microbes. I think that this is one of those questions that cascades from the level of soil microbes to insect gut microbes to human gut microbes, and just there’s so many layers to think about. I think that we’re going to see that developing as we learn more and more about these chemicals and how they persist in our system.

Sarah Beck: Our guest today is Aaron Anderson, Pesticide Program Specialist, Towns and Cities Lead, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Sarah Beck: I did want to ask you—invertebrates, that is a really big term, and I’m assuming you’re not actually conserving every invertebrate. Can you just give a little bit of the area of concentration of the organization of Xerces Society and just to cue us up to this?

Aaron Anderson: So, Xerces has been around since 1971 working to protect wildlife through the conservation of invertebrates in their habitats. Our name is a reference to the Xerces blue butterfly which is believed to be the first American butterfly to go extinct due to human development and actually lived close to where you are, in the coastal sand dunes around San Francisco.

Our area of interest are basically all invertebrates. So these are animals without backbones, but a lot of our work is insect conservation in particular pollinators like bees—native bees in particular—butterflies, but we also have people working on things like freshwater mussel conservation. We have a firefly program working to protect fireflies, and we work in agriculture areas, wildland areas, urban areas, really across the board.

So I think a lot of our species-specific work obviously, like you said, invertebrates are a really broad group. So we can’t be monitoring and intentionally trying to conserve every single one, but a lot of the work we do—the broader like habitat protection, pesticide reduction—does benefit this really broad group of animals that are so important to us and to ecosystems.

Sarah Beck: I was thinking, this is very on the spot, can you do a “5 Minutes and You’ll Love Invertebrates”?

Aaron Anderson: I don’t know if I can do five minutes, but at least a minute-long pitch about invertebrates.

Sarah Beck: It doesn’t have to be the typical charismatic species.

Aaron Anderson: So what I think is so cool about invertebrates is that we don’t notice so many of them. Especially different types of insects are so small, or they might just live places that we don’t go typically, like when you’re talking about aquatic species or nocturnal species that we just don’t see.

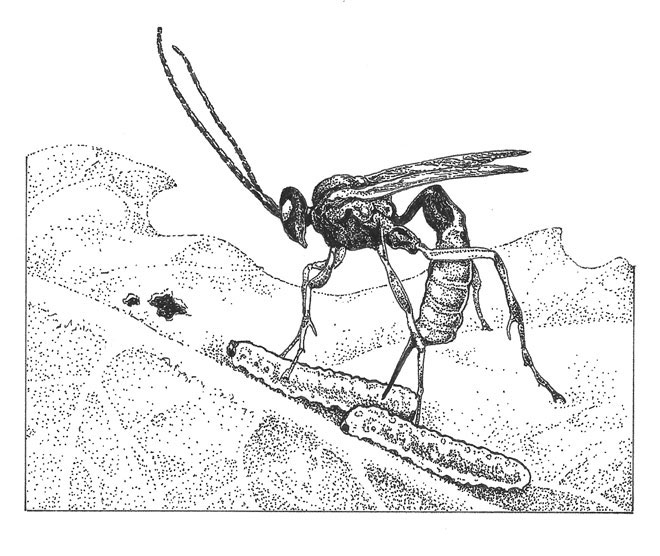

They do so many important things. For us, you think about pollination, you think about pest control, nutrient cycling, but beyond the ecosystem services and the benefits they provide to ecosystems as well, they’re just fascinating creatures. When you look at them closely, you have bees that are all sorts of different metallic colors. You have just a beautiful diversity of butterflies. You start looking at things like flies or parasitoid wasps, they have this cool morphology, like amazing antenna that are branching in different directions.

They’re just this really, really cool group of animals and a lot of us just aren’t aware of them when we’re out in a garden or going for a walk, because so many of them are so small. Unless you’re really intentionally looking for them, and you have an idea of what to look for, it’s really easy to miss them.

One of the really cool things that I get to do in my work is when I’m doing outreach, opening people’s eyes to the wonder of these creatures. I think that’s something that the more people appreciate how cool they are, how beautiful they are, how important they are the more yeah, hopefully the more willing they will be and more interested they’ll be in conserving them and protecting them.

Sarah Beck: I was thinking about the parasitic wasps. I mean, some of those are absolutely fascinating and a lot of them are pretty teeny tiny, right?

Aaron Anderson: Some of them are just, you almost need a microscope to really see them, yeah.

I think the cool thing about parasitoid wasps is that they’re an incredibly diverse group of insects. I think every insect on Earth, scientists think there’s at least one parasitoid wasp species that will parasitize it.

Sarah Beck: What!

Aaron Anderson: It’s an incredible diversity and hundreds of thousands of species. So many that scientists haven’t even described yet. But yeah, they can’t sting you. So instead of a stinger, they have an ovipositor, which is an egg-laying structure at the base of the abdomen.

Sarah Beck: So don’t be freaked out when you see that.

Aaron Anderson: Don’t be freaked out. Exactly. Yeah. So they’re going around your garden and in agricultural areas and natural areas and they’re laying their eggs in or on different insects and they hatch, emerge and consume the insects. And they play incredibly important roles in pest control both yeah, at home and in agricultural systems.

Sarah Beck: Let me just ask you a little bit more about your specific work, because your role at Xerces is the pesticide program specialist towns and cities lead, and I think the towns and cities piece is especially relevant and interesting. We’ve talked a lot about urban ecology recently at Pacific Horticulture, and I’m curious if you could explain what that important city town component is.

Aaron Anderson:, So I work primarily, as you were saying, in residential and urban areas, encouraging both private individuals as well as municipalities to reduce or eliminate pesticide use in order to protect invertebrates and encourage alternative pest control measures and pollinator friendly gardening practices when it comes to home gardeners.

I guess taking a step back, I’m guessing most of our listeners are likely aware of this, but there’s many recent studies that are documenting declines in insect populations and communities worldwide. In particular, many pollinators, including bees and butterflies, are imperiled.

That data is patchy since many insects—in fact, most insects—aren’t carefully monitored, but the data we do have almost all points to decreases in populations, and we know enough to know that it’s essential to take action to conserve pollinators and these other insects we care about. One of the leading causes of insect declines that scientists agree on is pesticide use or exposure to pesticides.

So despite that doom and gloom about insect declines I just mentioned, our residential landscape—so where we live, where we work, where we play—these landscapes can support beneficial insects like pollinators and, in fact, urban areas can actually support a surprisingly abundant and relatively intact bee communities depending on the location. Largely because we provide flowering resources from spring into fall, when bees are out flying in the form of flowering plants in our yards and in our parks. There’s some studies that suggests that some urban areas can also have a lower pesticide exposure than surrounding areas if they’re heavily agricultural, for example, so they can potentially serve as refuges as well.

So because of this, residential areas really do have a high conservation potential for invertebrates which is something I find really exciting, working in these spaces. I think that potential is even greater if we were designing and managing these spaces, thinking about the needs of these insects.

So when we’re gardening for habitat, invertebrates need food. they need shelter, and then there’s a final piece, which is protection from pesticides.

Sarah Beck: Right. So just to get into this the scope and the seriousness of the pesticide issue, can you give us a sense of just how much of an impact this has?

You mentioned the insect apocalypse conversation, and I think you’re right that I think a lot of gardeners are aware of this. But when we think about the climate change impacts and other issues. It sounds like you’re saying that the pesticide piece of this is a really big piece of our concerns about invertebrates.

For More on Parasitic Wasps

Garden Allies: Ichneumonid Wasps

Ichneumonid (ick – new – mon – id) wasps are harmless hymenopterans, nonaggressive garden residents, and enormously beneficial garden allies—yet few know them by name. Gardeners encountering ichneumonids will find them walking about on plants with a characteristic staccato movement. With their long antennae in constant motion, they go in search of a suitable host insect in which to lay an egg. Ophion species adults, fluttering around lights in the evening, are familiar to both gardeners and non-gardeners. While many species may visit gardens, few are truly common; many species can only be seen in their wild habitat. >>Read Article

Aaron Anderson: So of those major causes, habitat loss and fragmentation is the leading one, but then also, yeah, pesticide exposure like you were saying, climate change, different pests and pathogens. These are all contributors. It’s hard to disentangle all of these because they’re all interacting at once.

Insecticides are highly toxic to pollinators, not just pests. Some insecticides are more targeted than others in the groups of insects that they impact, but many tend to be very broad. They’ll kill the target pests, but also everything else.

So when they’re used in a residential area, in a garden, in a park, it’s not just going to impact the pest. These beneficial insects, pollinators, that are exposed to these chemicals will also be impacted. Modern insecticides are very potent and newer ones—you may have heard of neonicotinoids or neonics—that have been made to replace older chemicals, aren’t more friendly to bees and are often more concerning.

I guess I wanted to emphasize that we’re concerned about more than just insecticides. In particular, there are both fungicides and herbicides that have been shown to have some negative impacts on pollinators and other insects. Fungicides are often classified as practically nontoxic but some have been linked with some subtle yet still harmful effects.

One concern is that there’s some types of fungicides that will actually interact synergistically with certain insecticides, meaning they increase the toxicity when they’re present together. There’s worries about of some of these chemicals across the board, not just insecticides.

I should mention herbicides, too. The main impact of herbicides is that they remove flowering plants from the landscape. These flowering plants are what provide the pollen and nectar that bees and other insects rely on for food, but there’s also some studies that suggest that there can be some direct impacts as well.

One in particular suggests that glyphosate might impact honey bees’ abilities to navigate and potentially interfere with their gut microbiome, which might make them more susceptible to disease. These are called sublethal effects. So there are things that might not directly kill a bee, but if their navigation’s impaired and they’re not able to find food as efficiently and make it back to their nest as quickly, these little things can over time add up at the population level.

Sarah Beck: That is so sad to think about. It’s really tragic. I mean we think so much about how we want to build resilience generally within a garden and create all of the components to help support the complete ecosystem.

I know you probably also have some information on drift, or if you’re not the one applying some of these chemicals, but someone else nearby is, I’m sure there are concerns there as well.

I really would love for you to talk a little bit just about, how you and other researchers have done some investigation of the impacts of pesticides. I’m just very curious how scientists are even coming to understand some of these things. What you’re talking about is so complex.

Aaron Anderson: I can speak in more detail to some of the limited research that we’ve actually been doing at the Xerces Society. Even though we’re not primarily a research organization, we do dabble in some research, which is really great.

So I think on one hand you have, “Okay, what’s the toxicity of this particular chemical?” I think the other part of what you’re asking is also, “Out in the environment, what are these insects being exposed to? Where’s the contamination coming from? What is the actual risk?”

Over the last couple of years, we’ve been doing some pesticide residue sampling, because often we don’t really know what’s out there. How much contamination is there and what chemicals are there and where are they?

Before I started, there were a couple sampling projects that Xerces did with partners. One was looking at pesticide residues on milkweed (Asclepias) at sites up and down the Central Valley of California in a variety of different landscapes.

Another one was looking at pesticide residues on milkweeds from nurseries, actually, at 15 different states across the country to get a sense of when somebody is buying a pollinator planting for monarch (Danaus plexippus) habitat, what’s the risk of pesticide exposure?

So then I’ve been involved in two research projects that we’ve been doing. So in 2022, we sampled pesticide residues on butterfly host plants in Sacramento and in Albuquerque to get a sense of, in these urban areas, on these butterfly host plants those butterflies are relying on, what’s the background level of pesticide contamination that’s out there? I should note, we just got the results back from the lab for that. So stay tuned, hopefully coming up in 2024, we’ll have some publications from that.

In this past summer I led a sampling project looking at residues from residential mosquito sprays in Georgia, Massachusetts, and in Iowa to try to get a sense of the amount of drift that those sprays are producing and the risk those sprays pose to habitat, both in sprayed yards and in neighboring yards. You know, “I’m trying to create this pollinator habitat in my yard, but my neighbor’s spraying. What’s the risk?” So we’re trying to get at that a little bit.

Read more from Aaron Anderson on Pacific Horticulture

I Did My Graduate Research in a Garden Ecology Lab, This is What Gardeners Want to Know

There is surging interest in gardening for pollinators. Ideally, garden habitat would consist of a diverse suite of native flowering plants that provide resources for not just pollinators, but also the myriad of other beneficial insects that thrive in gardens. But people often only have small spaces available for planting or are overwhelmed by choosing from dozens of plants. In these cases, how do gardeners know the best plants for pollinators? I did my graduate research at Oregon State University (OSU) in the Garden Ecology Lab, and this is the type of information our audience—gardeners throughout Oregon—wanted. In the Pacific Northwest, there had been no comparative study of the attractiveness of plants to pollinators. Because of this, I decided to study top Pacific Northwest bee plants for gardens and other urban greenspaces. >>Read Article

See Aaron Anderson’s Plant Recommendations here.

Sarah Beck: I’m curious if there are some specific to the Pacific region issues. Certainly, we’ve been watching the story about the western monarchs. I’m curious if you want to talk a little bit about the monarchs or anything else that’s specific to the West.

Aaron Anderson: What I would say is taking a step back when it comes to monarchs, any type of butterfly or moth when you’re thinking about both providing habitat for them and then also protecting them from pesticides, there’s a little bit of a dual consideration because not only are they using the flowers for nectar and food as adults, but they’re also obviously feeding on the foliage.

So that increases their potential exposure to some of these chemicals because if a monarch is sprayed and the caterpillars are out there munching away on the milkweed leaves, then that’s obviously an exposure route that’s of concern, similarly as the adults are nectaring on the flowers.

So I think it’s just one of those things. When you’re thinking about any species of concern that you’re particularly interested in conserving, it’s important to think about the entire life cycle of that organism and all the different places that they might be at risk, whether it’s from pesticides or something else. And also the resources that they need and all of those different life cycles.

Sarah Beck: I actually think we might have skipped something that’s really, in the category of “5 Minutes to Love Invertebrates,” invertebrates are really weird creatures because they don’t have the same physical existence their entire life, right?

Aaron Anderson: I think that is one of the things that’s so cool about insects is the fact that—invertebrates—you’ll start off with an egg and then potentially a larva or a nymph. It’ll pupate, turn into the adult.

I think it’s something that’s really important to do is, yeah, when you’re interested in learning more about an insect that’s in your yard, do some research. Figure out what it looks like at all of those different life stages and where it might be hanging out, where it might be overwintering. I think overwintering sites are one of the really critical determinations of insect populations in your yard.

So it’s important to keep leaf litter because so many of our native insect species will overwinter as eggs or pupae that are underneath that leaf litter, even adults sometimes. And then sometimes those are the first ones that emerge in the spring because they’re ready to go because they’ve overwintered as an adult. We call it diapause, but it’s essentially insect hibernation.

You think of cavity nesting bees, these are small bees that will nest in something like the center of a plant stem with a pithy center that they can chew their little nest in and lay their eggs there.

So you might have some roses or caneberries, asters, that are in your yard, and you have those dead-looking stems, but actually you’ve got bee larvae inside that are going to pupate and turn into adults and emerge. So there’s all of these cool places in your yards where you have insects hanging out that you might not realize when you first look.

Turning it back around to the pest control issues, because we encourage home gardeners to reduce or hopefully eliminate pesticide use in their yards. When you’re thinking about alternative management, one of the most important things to do is to understand the life cycle of the pest that you’re trying to control, because then you can break that cycle either by interrupting the pest itself, physically or eliminating the conditions and resources that the pest needs to thrive.

So this isn’t just for conserving the insects you want, it also will help you get rid of some of those insects that you don’t want.

Sarah Beck: The power of understanding that life cycle.

I know we’ve talked before about leaving stems and the dead growth, letting that overwinter. I know, Aaron, I think you had told us before, be cautious not to go clean that up too quickly because those bees need a chance to emerge again, right, in the spring?

Aaron Anderson: Right, exactly. Especially when you’re thinking about stems. So if you have a plant stem that was a live plant that just died back, a bee’s not going to be able to use it that year because they would have. So you have to let that stem wait until the next summer when it’s a dry stem that a bee can actually chew its way into, and then you have to leave that all the way until the next year by the time the bees actually emerge and some bees do emerge earlier in the years, but some of them will emerge later in the summer. They’re not all emerging at the same time.

One of our recommendations is that, for those stems, just leave them up until they just start decomposing on their own. Don’t even worry about cutting them back. Because once the plant, if it’s an aster for example, puts up its new foliage, you’re not even going to see those older stems.

But yeah, you have to leave them for a couple winters, if that makes sense.

Sarah Beck: You need to slack off on being too fastidious.

Aaron Anderson: Yeah, exactly.

Sarah Beck: I keep wanting to ask designers to give us some, some tips on this. I think there could be a whole interesting design course on how you, how you camouflage.

Aaron Anderson: That would be a really cool conversation, honestly, to have somebody with those design skills talk about how they would incorporate habitat.

Sarah Beck: Or find a way to make it add texture somewhere, where it’s adding interesting dimension, where it’s not just going to look like, “Oh, there’s a dead thing next to a green thing.”

Aaron Anderson: Totally. And one of the things we tell people, too, is sometimes people want to have that more conventional manicured garden aesthetic, right? But you can have sections of your yard, maybe, that are less visible, but you can let be a little bit more wild and provide habitat.

There’s a lot of different ways to do it, which is cool.

Sarah Beck: As I always like to say, brown is a color.

Aaron Anderson: It is, exactly.

Sarah Beck: You have said that a very small percentage of insects in our gardens are actually causing any type of harm. I’m just wondering if you can give us a little perspective on that. Because I think one of the easiest approaches to some of these pest issues is sometimes, are you sure something needs to actually be done?

Aaron Anderson: You hit the nail on the head there. So the statistic that I’ve heard is that, when you’re thinking about pests and insects, only about 2 percent of described insect species are what we would consider pests, and the other 98 percent are directly beneficial to us or they’re otherwise foundational to ecosystems.

So the odds are overwhelmingly, when you’re looking and you see something small crawling in your garden, it’s doing something helpful. When you’re considering, “Oh, do I have to worry about this?”

Just because something is eating your plant doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a pest. Herbivores exist, they’re okay. Most hardy plants will be resistant to a good amount of herbivory. They’re part of that food chain, right? And then beneficial insects like predators and parasitoids will be feeding on those herbivores. You want those in your garden because those will help keep a pest outbreak from actually exploding.

So having this healthy ecosystem, having a little herbivory on your plants is a good thing, especially if you’re hoping to provide habitat because you need to have butterflies and moths, they need to eat plants as caterpillars.

Sarah Beck: When you’re starting with plants that are doing really well, those plants can handle a few munches on some leaves.

Let’s say you are suspicious as a gardener that there is a very real pest situation. Do you recommend taking a closer look when you want to figure out, “Hey, is this a pest?”

Aaron Anderson: Yeah, if something does seem out of balance, because problems do arise even in a really well-planned garden, then—like you were saying—the question is then when and how to intervene. Sometimes intervening with a nonchemical method is needed when something seems out of balance, or the damage is potentially a threat to the survival of the plant.

As home gardeners can tolerate more damage to plants than farmers can, for example, but at a certain point you’re like, okay, this plant looks like it’s really at risk. Or maybe the pest is eliminating the flowers that you wanted to provide for pollinators or something.

The first step is to get a firm identification of what that pest is, because then that’s the only way you can really understand the life cycle and how you might be able to take care of it. Smartphones are a really great gardening tool because you can take photos. So taking notes of whether you see leaf curling or browning or skeletonizing of leaf veins, things like that. Yeah, knowing exactly what you’re dealing with before you make any decisions about management is really important.

Next recommendation would be to contact your local extension service or master gardener hotline which often have a diagnostic lab or can otherwise identify or diagnose those issues.

Sarah Beck: Don’t shoot first.

Aaron Anderson: Yeah, no, you’ve got to understand what’s there. I think you were mentioning this earlier on, Sarah, is that the first foundation is prevention. Making sure you’re planting the right plant in the right place, it has the correct resource for it to survive, appropriate watering, things like that, because stressed plants have a much harder time mustering defenses to insect infestation or to disease. That prevention stage is super important for pest control.

Still at the stepped back level, we really encourage planting a diverse suite of plants, in particular including some native plantings to bolster populations of natural enemies. These are predators and parasitoids that will attack the pest insects.

These diverse plantings have been shown to increase the abundance and diversity of these predators and parasitoids, and that’s really the foundation of good nonchemical pest control, having that diverse suite of natural enemies.

Beyond that, for many diseases and certain larval infestations, just sanitation. So just removing that infested plant material is a really good choice to reduce the level of damage and break that development cycle of that pest or disease. You can cut infested flowers or other plant materials and throw it away. You don’t want to compost it cause you want to take it off site.

Sarah Beck: That is such a great point. In fact, that’s such a simple action, especially if when you’re seeing something, the damage is really concentrated in one spot. It could just be gone.

Some of these insects, you can just come up and be the aggressor yourself as the big, powerful human that you are.

Aaron Anderson: That is a great way to put it. That was actually going to be my next point. For a lot of insect outbreaks, handpicking or squishing them, knocking them off with water, for example, can be a really good first step. It can be a little bit tedious, but I’ve definitely done this in the garden with caterpillars, things like that. You just go out there, look for them, pluck them off.

And it’s deliberate, it’s cautious and it helps save other wildlife from harm. You have aphids, a quick blast of water can knock those off. There’s a lot of simple mechanical ways to deal with those pests.

Sarah Beck: I had a friend whose grandmother used to say, in relation to squishing insects in the garden, “You can wash your hands.”

Aaron Anderson: I love it.

Sarah Beck: You’ll be fine.

Aaron Anderson: That’s a great perspective. I love that.

Sarah Beck: I’m just wondering if you have some suggestions for gardeners who really care about this issue and maybe it’s a concentric circle thing. Are there some things within your neighborhood, within your neighbors, that there’s a role to play? Is there perhaps a community role to play in tracking this issue and supporting?

Aaron Anderson: It works on all levels. At the individual level, stopping pesticide use at home is something that’s really important and easy that you can do, obviously in your own yard, but then scaling up, like you were saying, at the community level.

Talking to your friends and neighbors, if you have a rapport with them. Tell them why you garden the way you do and your goals, and see if you can get an understanding of where they’re coming from and some of their concerns, maybe why they’re using some of these chemicals if they are. Then you can potentially provide information. I think that meeting people where they’re at thing is really important.

We have the Bee City USA program, is an arm of Xerces. One of the things that you have to pledge when you become a Bee City affiliate is to reduce pesticide use and to have an integrated pest management (IPM) plan.

If people are interested, I’d 100 percent encourage people to see if they can get a groundswell of support and make their community or campus—because there’s also Bee Campus USA—make their city or campus a Bee City.

I think one practice that ties into the home garden that’s worth talking about is the risk of pesticide exposure from plants purchased at nurseries. At Xerces with partners, we sampled those milkweed plants at nurseries in, I think it was 15 different states. We found that milkweed samples from that study had an average of 12 pesticides present, including plants that were labeled “bee friendly” and “we don’t spray neonics.”

The demand from nursery plants to be aesthetically appealing and pest-free and damage-free is really high. Yeah, so that’s definitely something to be concerned about, both when you’re buying a plant to put into your yard but also in a general sense, like okay, these pesticides are out there.

We’ve produced two fact sheets. One is “Buying Bee-Safe Plants” and the other is “Offering Bee-Safe Plants.”

I think the three basic steps as the consumer you can take are to ask for organic plants, avoid plants treated with those long-lived highly toxic systemic insecticides like neonics, and try to get to know nursery practices to see if they’re using pollinator-friendly production.

A lot of the nurseries might not know the answer because they’re buying them from growers and they might not know all of the particulars, but I think asking those questions will demonstrate consumer demand for bee-safe plants. Hopefully if more and more people are aware of the issue, it can potentially shift what some of the nurseries are offering,

I guess this is where I can dive and talk a little bit about neonics. Neonics are a hot topic insecticide when it comes to bee conservation because they’re highly toxic, and the other issue with them is that they’re systemic, which means the plant uptakes these chemicals and expresses them throughout the plant.

So the leaves, but then also the pollen and the nectar will all be contaminated with the pesticide.

Sarah Beck: So if you’re munching the plant or if you’re pollinating the plant.

Aaron Anderson: Exactly. You’re still going to be exposed to neonics. They’re highly toxic and many of them can be quite persistent, particularly in woody plants. They can stay for, in some cases, years. But for even an herbaceous plant, if you purchased a plant at a nursery that’s contaminated with neonics or has been treated with neonics for that first growing season, there’s likely going to be measurable amounts of neonics.

If you have a plant and you’re not sure whether it’s been contaminated with neonics, you can still plant it, but you can net it with like a fine mesh for that first growing season so that pollinators and other beneficial insects can’t actually access it, that risk of exposure is lessened. You can also try to knock some of the soil off of the roots. Sometimes these pesticides are applied as soil drenches, for the plant’s roots to uptake.

Sarah Beck: That’s shocking. I just had this assumption, you get a nursery plant, you bring it home, it’s got a very minimal amount of soil with it. And my assumption would have been that a short quarantine and these things dissipate. It sounds to me like the neonics are, like you said, persistent, which is very concerning and I think that raises enough of an alarm bell to say when you’re purchasing plants, you need to be asking those questions.

I do appreciate that you mentioned your resources. I want to say that we are going to include along with the transcript we’ll have a whole list of links and resources, fact sheets.

It’s so fun talking about invertebrates, even though it’s very tragic and sad. And I wish you hadn’t told me about the origin of the name Xerces. I knew that it was a butterfly, but I didn’t realize that it was tragically lost butterfly that was right near my homeland.

Aaron Anderson: I do want to stress, despite the doom and gloom about insect declines and the impacts that pesticides have, the fact that insects are really able to use these small habitat patches, yards, parks, things like that, which is amazing.

Sarah Beck: What does it look like when we design our urban spaces and our towns and landscapes within those to be without the harmful chemicals? That can happen. We can that future, right?

Aaron Anderson: Homeowners, renters, people who are managing our urban spaces, like parks, schools, all of these green spaces and urban areas are reducing or limiting pesticide use and using a lot of these other resources.

There’s a lot of cool organizations doing really neat stuff, trying to promote athletic fields being managed without pesticides. We have golf courses, places like that. The connectivity that would provide for habitat really does scale up to that landscape level and we can provide this connected habitat for invertebrates, but other animals and organisms as well across the landscape and provide connectivity to extant habitat on the outside of cities.

I’m having this mental image of this interconnected, green, wonderful urban space. I think that potential is there. We just have to make the conscious decision to do that.

Sarah Beck: I think I was not taking seriously enough the potential danger of bringing home a plant to my garden that I didn’t necessarily have a full origin trace on. There’s only so far you can take this information because it sounds like Xerces Society has discovered some instances, at least in some cases, of plants that were labeled as non-sprayed, that clearly had residue on them. This idea that bringing something home and letting it sit for a while or brushing off some soil, some of these chemicals are sticking around and the fact that they might still impact an insect, what, months later?

Adrienne St. Clair: I think that this is another place where we can have that back and forth with consumers and producers to kind of push the edge a little bit more. And sometimes producers push the edge in good ways. And sometimes we can push the edge in good ways. Have this evolving line of best practices when it comes to stuff that we’re bringing into our home.

Sarah Beck: On the positive side, Pacific Horticulture interacts all the time with some very reputable nurseries, and there are so many of them. There are many people in this industry who are alert to these issues and who are doing very careful practice around sourcing plants, tracking where those plants are from.

I just don’t think I had looked closely at the science, and some of the science is really new and some of this research is really new and it isn’t extensive yet, either, but it’s certainly enough to be alarming.

Adrienne St. Clair: I loved that idea that Aaron brought up of our gardens being able to be refuges from the greater community of spraying. So if you’re living in a more rural area with agriculture around you, your garden can actually be an insect refuge for those invertebrates that are in your area.

I had this 200-foot-level perspective of imagining all these gardens in an urban or suburban setting, linking up and being this refugia for invertebrates.

Sarah Beck: This is one of our favorite ideas.

There’s another element of this, which he really gently brings up, like that sort of nosy neighbor component, where we get to think about building our relationships with the other people who garden nearby. This isn’t about being aggressively confrontational.

This is where Aaron and Xerces really have a gift to share, which is, how do you have these conversations? Perhaps having a conversation with someone that might be using pesticides or herbicides in your neighborhood. Maybe there is an opportunity. There’s a lot of really nice entry points for, “Hey, if I think there’s an issue in my garden, if I think I’m having a pest issue, how do I really assess that?” Maybe there’s not even such a big problem.

For more from Aaron Anderson, you can check out his very popular article from last year, “I did my graduate research in a garden ecology lab, and this is what gardeners want to know.” That article can be found at pacifichorticulture.org.

Resources

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

Code, Aimée and Sarah Hoyle. 2019. Smarter Pest Management: Protecting Pollinators At Home. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

May, Emily. “8 Pesticide Myths Every Gardener Should Know.” Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, August 23, 2023.

Selvaggio, Sharon and Aimée Code. 2021. Buying Bee-Safe Plants. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. 2020. “Harmful Pesticides Found In Milkweeds Critical For Western Monarchs,” news release, June 8, 2020.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. 2022. “Harmful Pesticides Found In Milkweeds From Retail Nurseries,” news release, August 31, 2022.

Responses