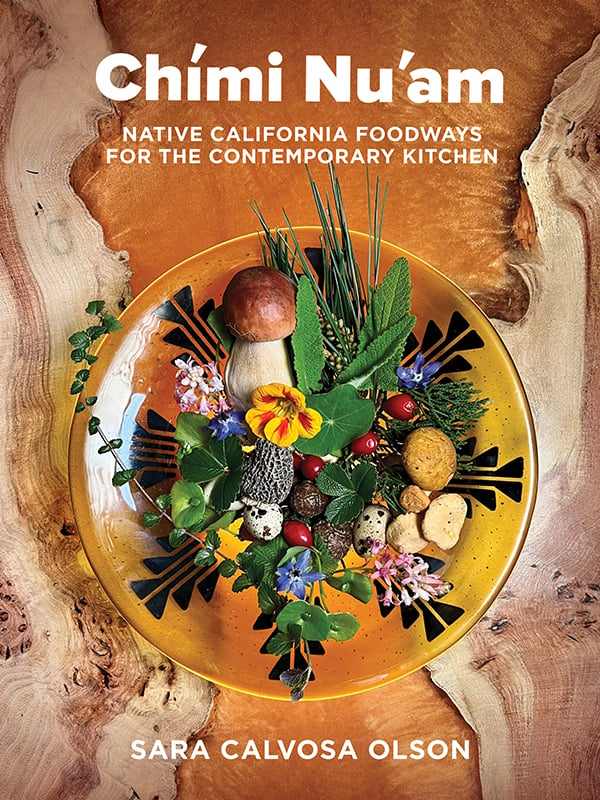

Book Review: Chími Nu’am: Native California Foodways for the Contemporary Kitchen

Contributor

- Topics: Nature is Good For You

Fall 2023

Before I begin with my review, let me first say that I am not a chef—even to say I’m a home cook is a bit of a stretch—which is why this is an uncritical review as far as recipes go. What drew me to this book was its focus on Native California foodways because of my work with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. During my time working with the tribe, I have had the pleasure of trying some Native foods, like bay nuts (Umbellularia californica), acorn (Quercus spp.), native hazelnuts (Corylus cornuta), and grass seeds.

Indigenous cuisine is not just about a plant or an animal, or an ingredient or recipe in this case. It is also about the relationship we create with our plant and animal kin. Native scholar Enrique Salmón, Rarámuri (Tarahumara), describes this relationship as “kincentric ecology,” which is an understanding that Indigenous peoples view themselves as part of an extended ecological family that shares ancestry and therefore care for all things, including plants and animals, because they are kindred relations.

It was no surprise that the author, Sara Calvosa Olson (Karuk), wrote a cookbook (foregrounded as an act of resilience and resistance to cultural genocide) that “requires a connection to nature and food gathering that you will need to nurture,” thus bringing kincentric ecology and relationships with wild food to our table. Olson encourages us to understand growth cycles, the environment in which the food grows, the ways in which Native peoples steward and prepare the food—and to give to the Native Elders in our communities first. Readers should not skip the introduction and head straight to the recipes.

Once you’ve read the introduction, you’ll find discussions of equipment and specialty foods, then a section about protein and stocks. From there, Olson lists recipes by season. While this cookbook is centered around Native foodways, health food stores carry many—but not all—ingredients. Though there can be some seasonal difference in timing depending on where you are located in California, a few general rules apply to harvesting wild foods. Spring is the time to gather greens and edible geophytes (underground parts—like bulbs, corms, and tubers). Summer is the time for berries and seeds. Fall is the time for nuts, like acorns. Fall and winter are the time to collect mushrooms, harvest shellfish at low tides, and hunt certain animals. For proteins, rabbit, and quail are used often in the recipes, but you will also find recipes with deer, elk, and fish.

The cookbook begins with fall. Before you get to the recipes, you will read about the importance of Indigenous burning to ensure a healthy ecosystem and the quality and abundance of culturally important plants, the effects of the prohibition on cultural fires and its relevance to climate change, and ethical gathering practices. Since fall is the time for collecting acorns (and other nuts), many of the recipes contain this ingredient. If you are concerned about how to prepare acorn and make a flour, Olson guides you through this process (you will need a blender and a food dehydrator).

Next, we move into winter and some thoughts about food security and the importance of community, taking care of each other, sharing, and winter preserving. Since winter is the time for hunting certain animals and harvesting shellfish, you will find recipes for quail, rabbit, elk, and mussels, in addition to recipes for stews and soups. This section also features some desserts!

Spring begins with what we all know and love: wildflowers! Wildflower seeds are an important part of Native diets and Indigenous communities intentionally managed coastal prairies and grasslands through the use of fire and sustainable harvesting techniques. Seeds, like redmaids (Calandrinia), are full of protein and fats and are useful in cakes. Because our regional wildflower displays are dependent on water, Olson reminds us of the harmful impacts of modern agricultural practices on biodiversity and ecosystem health, and that fighting for fresh, clean water should be at the forefront of our minds because the survival of our food systems depends on it. Since spring is a great time to gather greens, herbs, and flowers, this section also has a great discussion about safe and ethical gathering practices, as well as methods for dehydrating certain foods as well as producing decoctions, infusions, compresses, and poultices. The recipes from this season are filled with the bounty of spring and I’m particularly looking forward to trying some wildflower spring rolls and bigleaf maple blossom fritters.

Read Rick Flores’ Plant Recommendations from Pacific Plant People here.

Finally, we enter summer, a section that once again treats readers to a thoughtful discussion. This time, Olson talks about her own personal journey and the hopes that her cookbook will reach anyone who needs to find strength and healing, to nurture community, or simply to make some dietary changes—and that she hopes we know that we are not alone when we embark down the road of creating healthier relationships with ourselves and the food we choose to put into our bodies. Since summer is the time for berries, fruits, and vegetables, you’ll find tasty recipes like watermelon salad, three sisters summer salad, and blackberry smoothie bowl with hazelnut granola.

For those of you who think the recipes you will find in this book are too intimidating, Olson reassures us that this book is for everyone, even beginners, and that the recipes are “just north of Betty Crocker.”

To my readers who were hoping for a critical review of the recipes, I apologize. Again, I am not qualified to judge a recipe. Flavor is in the taste buds of the eater after all and it should be up to you to judge. I am looking forward to doing my best to try—to try to eat better, so that I can feel better, and to try to create healthier, more meaningful relationships with my environment and with the food I eat. Chími Nu’am is a wonderful cookbook that reminds us that Native Californians have been stewarding these lands for millennia and have developed deep relationships with the bounty California has to offer. Olson is inviting us all to be a part of that relationship, too.

To purchase your own copy of Chími Nu’am from our publishing partner, Heyday Books, please click here.

Responses