Stalking the Crop Wild Relatives with Garden Futurists Colin Khoury and Michael Kantar

Contributor

- Topics: Garden Futurist

Fall 2023

Listen to the podcast here.

There is a very cool set of native plants that are related to the plants we eat. You can likely find these Crop Wild Relatives in areas around where you live. These plants can help us better understand how familiar plants evolved, while they hold keys to helping us adapt in the future. Meet two scientists who are passionate about maximizing biodiversity on our plates, while racing against time to conserve plants that are critical to our cultural and agricultural future.

Garden Futurist talks to Dr. Colin Khoury, Senior Director of Science and Conservation at San Diego Botanic Garden, and Dr. Michael Kantar, Associate Professor at the University of Hawai`i at Manoa.

This episode was sponsored by:

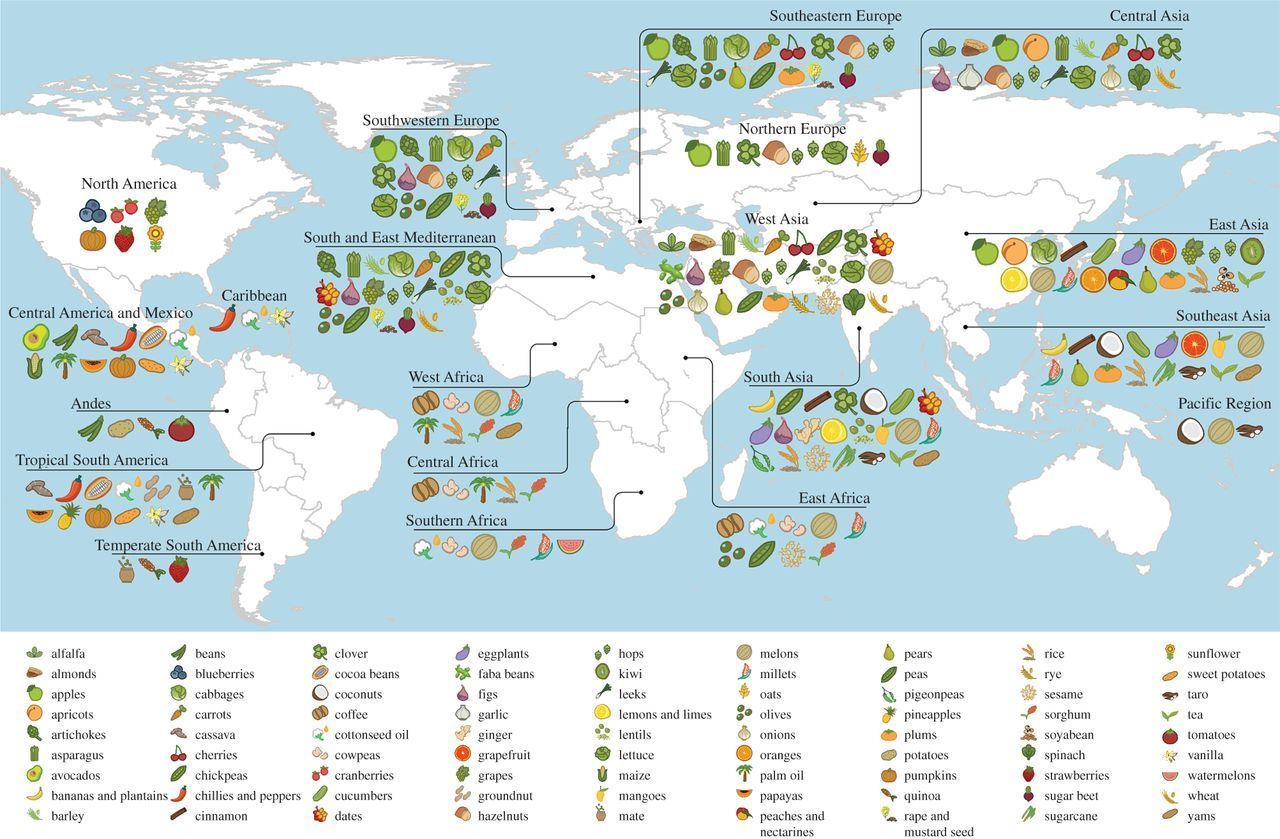

Image Credits: Published by the Royal Society @ 2016, by Colin K. Khoury, et. al.

View Article: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2016.0792

Sarah Beck: You’re listening to Garden Futurist. I’m Sarah Beck, here with Adrienne St Clair. Hi, Adrienne.

Adrienne St. Clair: Hi, Sarah.

Sarah Beck: We’re going to talk about wild plants that are related to the plants we eat. It takes us into some incredibly interesting periods of our history as humans, but it also takes us to really incredible places in terms of our future and our future resilience.

Adrienne St. Clair: I think crop wild relatives, one of the tricky things to think about is just how global our food is. All of us eat. We all have a relationship to food many times a day. When you start to realize that that connection to food could be lost because we only have one type of banana in our stores or we only have a few types of grain that could be lost with a fungal infection, that starts to become very personally relevant.

What I hope from what people can gain is that understanding translated to our natural areas, also. The wildlands, the woods, the forest, the backyard, your garden needs more diversity within it just like we need more diversity within our food. And so hopefully what you can take from this is seeing that personal connection, that very urgent need to be able to eat, and translating that to the natural areas in our neighborhoods, they have that same need for diversity to keep going.

Sarah Beck: I spoke with Dr. Colin Khoury, senior director of science and conservation at San Diego Botanic Garden, and Dr. Michael Kantar, associate professor at the University of Hawai`i at Manoa.

Sarah Beck: There are so many people right now who are interested in native plants. And people are growing native plants in their gardens and they’re excited to be supporting food webs and feeding wildlife.

And yet there’s this really cool set of native plants. They are the origin plants for what we eat, the native plants that are related to our food. Colin, Mikey, tell me about crop wild relatives.

Colin Khoury: I prefer to keep it simple with the definition that it’s simply wild plants that are related to our crops, which are the things that we grow, cultivate to eat, or for other purposes.

But I want to talk about terminology if you don’t mind. I want to finally clarify this issue after 20 years of challenge. Okay. Crop wild relatives is a sensical term because wild relatives is the important actionable term. They’re wild plants related to crops, but in English grammar, it’s grammatically incorrect to say a crop, then wild, then relatives, to put the adjective there. The grammatically correct term would be wild crop relatives, which is then nonsensical because, by definition, a crop cannot be wild.

And so the only solution is to get out of this conundrum completely and call them wild relatives of crops, which is one extra letter in the acronym. It seems to be too long for the community. They want to go with three rather than four letters. And so I think we’re stuck with crop wild relatives.

Mike Kantar: We need to get our celebrity endorser. It’s getting the Minions back into it. And the bananas at this point, right?

Colin Khoury: That is true.

Mike Kantar: Like as long as we can rebrand because they would for sure be able to get our extra letter.

Colin Khoury: Could we tell you two origin stories really quick? So you started this conversation by saying that people are really interested in native plants. And I think fundamentally most people are also interested in food.

Sarah Beck: Very much so.

Colin Khoury: My origin story, I think my earliest memory is sitting, our house was located on a hill and I was in a bank above the house and I was chewing on wild plants, which was common for me and common so much that my mother like called poison control very often when I was young. My memory is actually looking down at my little sister who was crawling around and actually eating cat food. I make jokes about how we have different diets still, but the origin story there for me has been an interest in wild plants and essentially eating them, using them, having them useful for food in agriculture since my very first memory.

The other origin story is how Mikey and I know each other and have come to appreciate each other’s work and we came to understand very quickly when we started to work together that we were both interested in making a real impact in the world and also how important communications and getting the word out to the wider public, not just other scientists or horticulturalists, was.

So we started talking about this and I think came to a realization that will sound silly, but if you think it through is very true, which is, if you really want to make a big impact in the world, how do you do it? And around the time we were meeting each other, I think it was Universal Pictures had its biggest financial success in its history, over a billion dollars of income from a Minions movie.

And this a cartoon focused on children about little yellow creatures that like to run around and help out and get in all kinds of trouble doing so. But they also love bananas. Love bananas. And of course bananas are an example, a poster child for genetic vulnerability, having very little genetic diversity in the number of crops that are major varieties around the world. And so we figured if we could convince Universal Pictures to do a short episode on the Minions trying to save the genetic diversity of the bananas that would go out, of course to children, but also to their parents who would watch this, it would have a larger impact than any publication, plant breeding, horticultural work that we had done or will ever do in our careers.

Sarah Beck: So would you have them go out and actually look for some wild crop relatives?

Colin Khoury: Yeah, they would get in a bunch of trouble, of course. Wild relatives center around where the crop comes from, where it was domesticated, because these wild plants are what the crops came from originally, some thousands of years ago when innovators, Indigenous peoples figured out that they could start cultivating and growing and making them bigger and tastier and whatever else.

And so for bananas, it’s largely Southeast Asia and into the Pacific, areas like Borneo and such. So in this movie, the Minions would be going to very tropical, very interesting adventures and get in all kinds of mishaps. And then the other side is very easy for them. They’re lab folks already.

So they would definitely go in the lab and be able to figure out how to bring the genes into the cultivated bananas.

Mike Kantar: Also, I’m expecting a heist from a gene bank at some point. So they need to steal technology from like Fort Collins, like the USDA national, like the cryopreservation and stuff. Then clearly, they’re going to use that to save the banana because someone wants them to not save the banana.

Colin Khoury: The irony would be that they would be stealing something that the USDA would be giving them freely anyway, if they just asked.

Sarah Beck: That would be funny. I would like that. And actually it made me think of the question I wanted to ask you next.

When you are in a wild landscape, when you see these plants, sometimes they look like a plant that’s familiar and sometimes not, right? Can you talk a little bit about that?

In the West, you think of like, there’s a lot of berry plants that the wild relative is very recognizable, or maybe sunflowers, but then you think of like teosinte or even probably origins of things like wheat probably just looked like a nondescript grass. How would you describe these visual characteristics of what the wild relatives look like?

Mike Kantar: Like you say, there’s a huge range and it really, really depends. You’ve hit on a question that botanists have been working on for thousands of years, not always in a classical Linnean classification, right?

Everyone has different names for the different species that are similar to one another. Sometimes it is really, really easy to tell that this is a wild plant. A lot of our plants that we use haven’t actually changed that much due to domestication.

Apple’s a great example, right? A former professor of mine talked about doing collections of wild apple in Kazakhstan and like, it’s a wild apple forest and a lot of the apples, he’s like, “Yeah, they tasted good,” and it hasn’t changed all that much. Others, like you brought up maize and teosinte, have changed a lot, and teosinte tastes terrible.

Colin Khoury: Part of this comes down to how difficult or how easy it is to change a plant. One can imagine that an annual that you grow every year and you can select out of a big population, because there are little plants that can grow right next to each other—like a grass like wheat or maize—could be a lot easier to evolve over hundreds and thousands of generations than a tree where you’re growing that tree up, and then to get a next generation is many, many years.

So the speed of change and of evolution of, for instance, tree crops and perennial crops. This is very, of course, known in horticulture as well, that it is typically slower than in annual crops.

And then of course, there are crops that are older than other crops. And some of these founding cereals or some of our oldest, eh, arguably some of our oldest, there’s lot to be found out about different domestications around the world, not just one place. Easily around 30 different sites around the world where there was a lot of domestication going on, again by Indigenous peoples.

Some of that well that started in some places at least 12,000 or more years ago. In some places, major domestications only happened a couple hundred years ago. And of course, all this process still goes on. There’s still domestication happening and all of these crops are still evolving and therefore being domesticated.

Sarah Beck: That actually makes me want to jump to the map that you made, Colin. It’s a map of the world and there are these cute little plant icons all over different areas, and those different icons, they’re of different things, plants that are fairly recognizable, but you see how they cluster in certain parts of the world. For instance, you’ve got in South Asia there’s like an eggplant and a coconut or a melon and West Africa, you see the coffee beans or cow peas or whatever is there.

I think for even those of us who are not steeped in the science of this story, I think it just makes inherent sense to us as eaters because the world has so many interesting, diverse foods. We know that a lot of these foods have come to us from different parts of the world, but this idea that there’s an origin story for each of these plants and that they come from somewhere on that map.

I’d like to hear from both of you on how this understanding has influenced you, because I know we’re going to get into some conversations about food diversity, too.

Colin Khoury: Thank you. I really appreciate that this has been interesting to you and it’s been one of the most fun and interesting works that I’ve had the chance to do in my career, to do something really simple, which was to try to dig a little bit deeper into and try to also compile and synthesize knowledge about where crops came from, where they’re domesticated, and where these wild relatives occur.

And on that note, by the way, we don’t really know the precise location of where almost anything was domesticated, because, also, that wasn’t one event. It was many people over a period of time. We can know regions, we can know general areas where there’s a lot of likelihood that that’s where the crop arose, came from, out of wild plants with people there. Those evidence come from where those wild relatives are, and also usually a lot of varieties of this crop, old, traditional, heirloom, landrace varieties that will be there because people have been there for a long time, growing them for different needs. Genetic evidence, linguistic evidence, archeological evidence, lots of pieces of information that come together to get a good guess of where a crop comes from.

My memory is that I was taught that agriculture arose in the Fertile Crescent, that is true, but that is not the whole story. Agriculture also arose in many other places independently, and some happened a little earlier, some happened a little later, but that was only part of the story. And so the map really tells that story of independent innovation, human innovation, human and plant, and also microbes and all kinds of other things, innovating together, working together to basically mutually benefit. And it’s not just one place.

So you get these hotspots around the world where people were really innovating. And those are not just people. It was also interesting locations, usually with a lot of topographic diversity or environmental diversity, also human diversity, lots of different cultures, interchanges like Turkey where it’s Asia meeting Europe meeting Africa where all kinds of things happen people-wise and plant-wise.

It makes sense once you start to think about it. Of course, there’s different dishes and different cultures and all of that, but what was more powerful to me was coming to understand that many people had never really thought about plants having a history. It was like they just were always there. So realizing that everything has a history and has a trajectory has been a really powerful realization for me, but also, I think, hopefully for other folks that started to put that together.

If you look down at what we actually eat, which is usually not a food, but a dish, a meal, it’s a combination of all of these different things that actually usually come from all over the place. And that’s true even of a traditional dish, like something that’s been around for thousands of years in a place, it’s like the national dish.

The national dish of Bhutan is a bowl of chilies with cheese on it. And those chili peppers did not come from Bhutan, they came from across the world originally. It actually is not only a story of origins and of how we can celebrate diversity around the world, but also of the mixing and matching and innovation and contributions and moving and migration and bad stories, good stories.

It’s the whole human story of 12,000 years that comes together when you look down at your plate and are benefiting from, hopefully, a bunch of diversity.

Mike Kantar: This map, I use it all the time. Like you said, Colin, it’s their introduction into food. I mean, everybody eats. It’s inherently interesting to people what they’re eating,

Sarah Beck: I want to zoom back in close because I want to think about here, even just in our own region. We’re in the Pacific region and I think this idea that these crop wild relatives are out there. Mikey’s in Hawai`i. Colin, you’re in California. Can you go outside and look for these?

Mike Kantar: Yeah.

Colin Khoury: There are groups of plants that were domesticated in this region, in North America at least. And those are of course the sunflowers but also pecans and cranberries and blueberries and various other berries and such. And so there’s a bunch of their wild relatives that occur in the Pacific region. You can find tons of strawberries and types of currants and Vaccinium and such all over the place.

And then there are crops that were domesticated in other regions of the world, kind of similar let’s say temperate like the Pacific Northwest, let’s say that areas of Asia or Europe, and their relatives are here in North America. And so they might not be the progenitor, the one from which the crop came, but they’re a cousin.

So for instance, you can find walnuts very easily around here in Southern California, or types of Prunus, types of apricots, peaches that were domesticated in other parts of the world. But there’s tons of diversity around in the canyons of San Diego, for instance, you can find some of these things.

And then there are also plants that they are weeds. They came from other places and they’re wild relative weeds. So they are two things at once. They’re interesting as wild relatives and potentially interesting for plant breeding, and they’re also sometimes a real management problem.

So again, in the Pacific region, especially in Hawai`i, of course, major, major issues there, but also in California you can find wild relatives of all kinds of crops. For instance, here in Southern California, the mediterranean area, tons of types of wild lettuce and wild beets all over the place. Usually in your backyard or any urban lot, you will find a wild lettuce, for instance, wild oats for instance, as well.

Sarah Beck: Mikey, you were mentioning breeding a little while ago. Can you give us just a little bit of a sense of why these crop wild relatives are so important to plant breeding or just in general? What are the important applications here of having these plants?

Mike Kantar: One of the things that’s cool about plant breeding, it’s an independently derived technology in every single culture where you domesticated a crop, they learned how to breed plants, learned how to make crosses, learned how to make observations.

So it is such a common technology, lots of different places use different words, but that’s what it’s been, and it’s been independently derived hundreds if not thousands of times by basically every culture around the world.

These wild relatives of crops are so useful because they live in weird places. They tend to be extreme in their ability to respond to things. So whether that’s disease resistance, whether that’s stress resistance to heat, to flooding, they by necessity have to be able to live in these wild and crazy environments.

We manage our agricultural environments so that our plants don’t have to deal with that, right? But in a lot of cases, and increasingly this is an issue, we cannot manage away certain things, a disease outbreak happens. A lot of times we narrow the genetic base of crops just like we did in banana.

So a lot of times the only resistance to a disease or the only tolerance to heat or salt only exists in these wild relatives that have evolved in these extreme environments. And so as long as you can make the cross, it might take a long time, but you can get that trait in to the plants that we eat all the time.

Sarah Beck: So the climate change pressure and the need for food security, that all comes into this story, right? Can you talk a little bit about what your lab is working on?

Mike Kantar: So a lot of the stuff that my lab tries to think about is we’ve done a good job, not a great job, but we have all of these plants that are conserved in these wonderful germplasm banks and in farmers’ fields across the world. Too many, in some cases, to practically breed with. If you have 10,000 plants conserved, how do you choose which ones to use?

So these boring, practical questions, in a lot of ways, of how do you operationalize this amazing diversity that we find everywhere? And in some cases, you can do it very quickly. There’s a lot of cool literature now about how quickly we can domesticate stuff relative to how long it took farmers to do it.

There’s instances where we can redomesticate wild tomatoes in like five years, instead of the thousand years it took before, right? There’s domesticating of crops that we never thought were going to be crops. Something like in the Midwest with cover crops, right? Where in 10 years we have something that’s essentially a crop that was a weed 15 years ago. How can we use all this amazing diversity, all this knowledge that we’ve built up historically, biogeographically, and genetically, and can you make that go faster?

Because while plant breeding, we know a ton about it. We touched on this a little bit earlier when Colin was talking about the difference between trees and annuals. Time isn’t time. Time is the generation length of a plant. That can be that can be six weeks or that can be a hundred years. Plants don’t care about human timelines. They just don’t. The goal of plant breeding is to always select plants that will have a benefit for people.

Sarah Beck: Now you’ve both made references to germplasm and the USDA repository. Let’s define a few terms. Can one of you explain germplasm and also just how the repositories work? Colin, you lived in one. Maybe you should jump in.

Colin Khoury: That’s fair. Actually, quite a few. I worked in a nonprofit seed bank in the Southwestern United States for some years, focused on preserving Native American varieties of beans and corn and squash and chilies and such.

I spent about 10 years in our international seed bank system, gene bank system in a center in Colombia that holds the global collection of beans in cassava otherwise known as tapioca in the United States and a few other crops. And then was in the USDA’s national seed bank system in Fort Collins for some years as well. And now run a largely native plant seed bank here at San Diego Botanic Garden.

So I can’t get away from the seed banks. I consider myself fundamentally a conservation scientist interested in preserving that diversity for present and future generations. But that wasn’t the origin of these systems.

They started out largely as places really for use for plant breeding. And so that happened early on in a couple of places, including the United States and also in Russia. That’s a well-known story of an early visionary who was really understanding that there were crop failures in Russia, wheat and other major crops, that were caused by genetic uniformity. He was an early geneticist.

Sarah Beck: Yeah, we’re talking about Nikolai Vavilov, aren’t we?

Colin Khoury: We are indeed. He’s more and more known.

He’s an interesting story. So he started to piece together that as a geneticist and many other things, including a geographer and adventurer and a pathologist, that that uniformity was leading to these catastrophic failures and therefore starvation, and that that uniformity might be able to be addressed through diversity, through breeding, through bringing in resistance, and that we needed to find it. He needed to find it. And so he became an adventurer and eventually became one of the widest-traveled persons of the world of his time, which was 100 years ago to 120 years ago. And this was well before, of course, a lot of mechanized vehicles in the places that he was going, like way up in the mountains in Central Asia and in the Horn of Africa and across Mesoamerica and such.

So he is known for collecting and bringing all that stuff back to Russia and then trying to start the plant breeding system in Russia to help address that genetic vulnerability. He’s also known because those voyages gave him a lot of insights, again, about where crops come from and how plants have evolved and diverged, as did Darwin and others who traveled and started to understand plant evolution through seeing that diversity around the world.

It was not fundamentally a conservation initiative. It was about using those materials, but because also in the last hundred years, essentially from the time that Vavilov was active, agriculture in the entire world has changed tremendously. Agriculture has changed tremendously through industrialization and innovation.

Again, technology and the world has also changed through globalization, economic development, migration, and a million other factors. And so all of this diversity also has changed and a lot of it has disappeared. And he saw that happening, too. His bank was really not about conservation, but he was already thinking about and talking about a little bit about this loss.

And so in subsequent decades, people became very worried. And in the ‘60s and ‘70s into the ‘80s and ‘90s, there was large scale efforts around the world to bring that stuff into those seed banks as much for conservation purposes as for the utilization purposes. And so now those banks are really about both of those endeavors at the same time.

Sarah Beck: That’s like the perfect balance between Colin and Mikey. Mikey, would you say that you are one of the utilizers of these genetic resources in terms of application and Colin is preserving them?

Mike Kantar: Yeah, and I think it’s one of the great examples of how all of this stuff that we talk about in terms of science is not a single person endeavor. It’s people working together. It’s people understanding where their interests align, and then trying to help basically help each other where you can, and then be fluid with how you allow others to use that information.

When we’re working on food, we’re trying to feed people. We’re trying to help people. And so that goal leads to, I think, that the necessity of collaboration and the necessity of really trying to share information.

Germplasm is just an individual population or an individual genetic line that is stored. When we talk about it for, say, soybean, you have the germplasm collection at the USDA. So the assemblage of all of the genetic lines has about 1,000 wild soybeans, has about 5,000 landrace soybeans, and has about 15,000 modern lines.

And so a line in this case can be referred to as a line, an accession, a variety, a varietal, a cultivar. Depending on who you talk to, they will use all of those different names to roughly mean the same thing.

One other very important definition is something called passport data. So for a lot of the stuff that we want to do, you want to know where things were collected, and so the passport data is exactly what it sounds like. It tells you where, when, and by whom, ideally, things were collected or deposited.

Sarah Beck: So when we’re referring to all those soybeans, just the physical manifestation of that may be seed.

Mike Kantar: It will be seed, yes.

Sarah Beck: Okay. But it could be preserved in different ways?

Colin Khoury: So I do think terminology is important and it’s important for clarity of understanding and also whether we’re being inclusive or exclusive in our communities.

So germplasm is an old word. It’s been around for a long time. I personally don’t like it because nobody really understands what it means, and it sounds like something scary, germs.

A common term, actually two words, is genetic resources, and that is very used. So plant genetic resources is basically all seeds and other things that are used for plant breeding. There are some that don’t like that term because resources is a term itself that has become a bit of a controversial term in the sense that it’s seen as something that humans are just trying to exploit as a resource, natural resource also has become one of these controversial terms.

So what that’s about is the increasing understanding also throughout these decades that these biological entities that are in seed banks, for instance, are not just resources for plant breeding, but also have been and continue to be really important to Indigenous livelihoods and evolution of biotic processes, including pollinators and all kinds of other things. And so resources feels too limited in its way of talking about it.

One could just say seed. So there’s a term, seed bank instead of gene bank, and I use that for San Diego’s seed bank. But that’s not wide enough and inclusive enough for the whole community because it’s not just seeds that are held. Very often, it’s other types of plant material that can be propagated: vegetative tissues, potato, potato clones, things like that. Increasingly it’s also actually isolated DNA, or pollen. There’s many ways that you could preserve interesting materials for plant breeding and many other purposes.

Then there’s gene bank, which is also a term, but that’s also limited because it’s not just about genes for folks, it’s also about knowledge and passport data and all kinds of things.

So we don’t have a perfect term, I believe, in the world for this right now. And so if there are any listeners that want to propose one, I’d be really happy to hear it.

Sarah Beck: You make so many great points there. It also just helps to illustrate in people’s minds like what we’re talking about, there’s this whole variety of material that could be preserved and cared for in order to do a variety of things in the future.

Colin Khoury: So there has needed to be some terminology around varieties created by people. And in different parts of the world, there’s been different terms, and that can be landraces, that is a variety or race of a crop that was evolved in a place on land by people in a local location.

It also has been called peasant varieties, and you can imagine that that can be a problematic term. They’re called heirlooms often in the United States, and there’s some other terms for this but it all really means the same thing. It’s a variety that was really produced locally by people as opposed to a variety that was developed by scientists like Dr. Michael Kantar here.

Sarah Beck: Mikey, can you give some examples of plant breeding, whether it’s your lab or others where this other methodology is being employed, and also where some of the sources for genetic material are vaulted in a library?

Mike Kantar: For example, one of the first projects I was working on was using these wild relatives of crops, in sunflower. We started a project probably back in 2002, and now crossing wild-collected perennial sunflowers to our domestic annual sunflower. And now 21 years later, there’s finally material that’s in a proper plant breeding trial, not just screening things to see if they’re cool, but a proper trial, and going through all of those different steps. Discovery, growing out all the wild plants to see which ones were interesting. Cross, the validation. Are they doing what we’re doing, crossing with the individual plant?

So now maybe there’ll be a release of these perennial sunflowers in 2025 or 2026. They basically look like annual sunflowers, but they have tubers like Jerusalem artichoke.

This has basically become domestication in real time, is what we’ve been trying to do, where the starting material is crossing a wild plant by a domestic plant. And it’s still probably not anything that a farmer would be comfortable growing because of the risk, but the thing is it’s really cool material, but it will have taken 23 years by the time it’s released.

The plants don’t care about our timelines is more the point there, but we can do all these things and it’s super cool, but I think it’s never the work of one person and it’s always this iterative process.

Sarah Beck: We had Tim Crews from the Land Institute at Garden Futurist last month, and he said some similar things. I want to just get you both just for a second here, to give me a little bit of the big picture visionary potential here, because when you mentioned this idea of moving an annual crop to a perennial, there are all kinds of implications there, right? You’re treating farming suddenly like an ecosystem.

There’s just so much value here in all of these seeds and the other material that you can grow plants from. They’ve got all of these amazing wild relatives. You’ve got all this stuff to work with. What’s the future potential here?

Colin Khoury: A couple years ago, I really had the opportunity, it was a tremendous gift to get to focus in on one project for a little period of time, a couple years actually. And I was trying to unpack what’s really happened with the change over time and all this diversity in the last, let’s say, hundred years. And we wrote a big review paper using the central term in the field, which is called crop genetic erosion, the loss of genes of diversity. There’s been a term that you will see, a statement that you’ll see in almost all news articles about this change in crop diversity that says that we’ve lost 75 percent of that diversity. You’ll see it around a lot, three quarters of this diversity.

Actually who came up with that and where that comes from has always been a mystery to me for over 20 years. And so I really tried to dig into that and provide an answer to that in this paper. But in this context, I bring it up to your very deep and interesting question about what is our future and how can this diversity help us or is there a positive future? I end the paper really trying to get there.

And there’s of course a lot that we need to do. We need to do all this conservation stuff. We need to do all this breeding stuff. There’s so much that we need to do in the world to keep up.

It really necessitates societal change, value change, even perhaps like deep evolutionary change of humanity, of understanding how our interconnectedness, I believe in a sense, I don’t mean that in a wishy-washy way, but how much we depend on nature of biodiversity, on each other, on food systems, on plant breeders, on all of these things, and valuing that. On farmers. Our economic system in agriculture, whether you’re in a capitalist system, a communist system, or whatever else, fundamentally does not value this diversity. It devalues it.

Mike Kantar: I think that people are very clever. I think we’ve developed situations from a technological, from even a socioecological perspective, that we do understand what needs to be done.

But I do agree that the idea is it’s a societal change issue. It’s not a knowledge issue, it’s not a knowledge gap issue. The idea is what are we valuing societally? What are we valuing for us to actually want to make these changes that we see? Globally, I think we are going to have to confront these issues because clearly the status quo doesn’t work.

We’re seeing increasingly drought and flood in the same years. We’re seeing catastrophic crop failures in certain places, right? We’re seeing climate change is causing new disease pressures, new abiotic stress pressures, like we’re seeing this convergence of all of these things.

I think one of the things that we have to fundamentally address is we have to explicitly discuss what were the decisions that were made that led us to the current food system we’re in that has some very large weaknesses, right? Particularly in the way that we’ve completely ignored that environmental sustainability piece is a huge one. I don’t think they’re insurmountable, but I do that we have to be honest in policy circles and honest in what is the goal of the system that we’re doing.

Sarah Beck: Maybe this is the time to talk about the taco diversity project, because there is some opportunity for us to celebrate the crossroads of cultures and the mixing of food stories. There’s some amazing solutions to the current challenges, humans do still have a chance to do make some of these changes.

What are some of those actions that you would see especially utilizing all of these, the germplasm, what we know, like where can we go with this that could bring that optimistic future? And how does celebrating diversity of foods and food cultures, how does that even interplay in that vision?

Colin Khoury: I think that we can come back around to the theme of communicating with the wider public and going beyond our communities. Here, at least in San Diego, most people understand it intuitively and know what we’re talking about, and most people enjoy it.

And so tacos would certainly be way up there on the list of what we consider to unify us, no matter what cultural background you come from, what job you have and all of that stuff. It’s the same idea. Can we work on something that is unifying us to understand and explore and appreciate a theme that I think is important? Back to that idea that I think that we do need culture change around biodiversity and around food and agriculture and all of this.

So what we’re looking at is a bit of a play off of all of these food competitions that are around of the best restaurant and the best this and that, but really what’s underneath it is celebrating food vendors, restaurants, innovators, who are doing interesting things with diversity in food, in this case in tacos, and having that be sometimes a little bit of a competition, sometimes a social networking process among people who are looking at these menus and restaurants and trying to count the different types of tacos, and the different ingredients within the tacos, and the different sauces and what chili pepper varieties might be in those sauces, which would necessitate conversations with the preparers and chefs and therefore deepen relationships and appreciation and hopefully many knock-on effects.

And so we’re just getting started on this taco diversity, and if you come down to San Diego, feel free to come see us at the garden and we can talk tacos.

Sarah Beck: I’m so excited about this. Now I do have a science question, though, related to this. Is an exceptionally biodiverse taco one that has just the longest species list contributing to it? Or do you have some other criteria? You were mentioning cultural elements. Are there bigger points for other things?

Colin Khoury: Really, and a very important point is that there’s a lot of ways of understanding and there are a lot of types of diversity.

There are species-level diversity, there are meal level—that is a taco itself—there is varietal level diversity. There is cultural diversity, there is the people doing it, which in San Diego is not just Mexicans in this case, but a bunch of people that work in taco shops, and Korean tacos and all kinds of innovations happening.

And so my point there is not to say that one is better than the other, but to realize and appreciate that there’s many types of diversity. And so the real challenge there is condensing that and simplifying it in a way that people could get those messages.

Adrienne St. Clair: I think the thing that crop wild relatives brings up for me is our disconnect that we have with food and the fact that food comes from some plant very long ago that that we’ve worked with to create our food. So I think that disconnect between wild plants and cultivated food is something that shocks people.

So just to remember the fact that our cultivated plants and our medicines and our fibers that we use for our clothes all come from something “natural” that grows in the wild, I think helps us remember our own connection to the natural world in a way that other things can’t.

Sarah Beck: I think there is some really essential knowledge, especially when we start talking about climate resilience and we start talking about the big picture of the ecology and conservation and what is really important. I think our conversation with Tim Crews was really deep on soil and thinking about stewardship of the landscape and how a specific set of crop plants, the grains, are really part of that story and how we’re really not doing a good job with soil and water, for the most part, with a lot of that very important set of staple foods.

Adrienne St. Clair: Well, let’s talk more about the last conversation with Tim.

Sarah Beck: I was really excited by this idea of what would large-scale farming look like if we treated it like an ecological garden, right? If it was a polyculture, if it was intended to be somewhat self-sustaining, if the soil was being improved through the process, if water was being conserved, if we weren’t throwing a whole bunch of nitrogen fertilizer and having runoff, like if it was like, “Hey, I’m going to take this fantastic ecological gardener’s methods and just blow that up to a massive scale.”

Adrienne St. Clair: So then this conversation in contrast feels more like, “What if we took the massive scale of the crops that we do now and look back to their individual scale within the habitats that they developed in, where they came from?” To realize that some of that is within our own ecosystems or within places that we’ve visited or that there’s a cultural tie to those histories that we can’t see on this massive scale of agriculture.

Sarah Beck: I think the whole conversation about seed conservation and including this idea of crop wild relatives and germplasm, I think there is a powerful relevance in terms of our interest in resilience that it’s important for us as gardeners to place ourselves in space and time and really understand how important this massive biodiversity is and what that might do for us in the future.

I’m saying this in a really pragmatic way, not a philosophical way. There are all of these plants whose genetics needs to be preserved so that as things change, we’re able to pull from that.

We want to have all of those in the bank, in the library, or both, so that we can adapt.

RESOURCES

Dr. Colin Khoury is senior director of science and conservation at the San Diego Botanic Garden.

Dr. Michael Kantar is an associate professor at the University of Hawai`i at Manoa and principal investigator for Kantar’s Lab.

Colin Khoury credits botanical artist Peggy Duke for inspiring his maps with her own “Centers of Origin” series of maps. A profile of Duke that includes her art and maps appears in the Winter 2022 issue of American Botanical Council’s journal HerbalGram: “Remembering Peggy-Ann Wetmore Kessler Duke: 1931–2021.”

Khoury, Colin K., Stephen Brush, Denise E. Costich, Helen Anne Curry, Stef de Haan, Johannes M. M. Engels, Luigi Guarino, et al. 2022. “Crop genetic erosion: understanding and responding to loss of crop diversity.” New Phytologist 233 (1): 84–118.

Origin of Crops Article: Origin of crops | CIAT Blog (cgiar.org)

Where Our Food Comes From (islandpress.org)

Genetic Erosion Paper: : https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17733

Crop Map Video: https://youtu.be/kySeEaR_8pA

Inspiring Bean Song Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fo6449Rd3I0

Responses