At 10, Seattle’s Pioneering Food Forest Pivots to Increase Food Security

Contributor

Winner of the 2024 GardenComm Gold Laurel Medal of Achievment for Articles, Magazine Consumer/Trade.

Summer 2023

What started as a student design project in permaculture became Seattle’s Beacon Food Forest—based on a simply radical, somewhat mind-blowing concept for urban planners: growing free food sustainably. This was not just a food forest, but a community food forest, open for foraging for all, located just two miles from downtown. Having just passed its tenth anniversary, where is the Beacon Food Forest today, and how is it changing?

The project’s launch in 2012 fueled massive media coverage around the world, inspiring like-hearted community-based agriculture activism. When it opened, Washington news site Crosscut reported, “There is no other project of Beacon Food Forest’s scale and design on public land in the United States—a forest of food, for the people, by the people” (Mellinger 2012).

With about three planted acres, the volunteer-run Beacon Food Forest is not the largest public food forest in the country—that title goes to the seven-acre Urban Food Forest at Brown’s Mill in Atlanta, Georgia —but it remains a dynamic symbol of urban food justice that is evolving with the needs of its community and societal and climate pressures.

Food Forestry for Today

Modern designers are rediscovering the ancient concept of a food forest as they work toward greater food sovereignty and sustainability. Used by Indigenous populations worldwide, it’s a planned plant community that’s designed for foraging and mimics the structure of a forest—every level is edible, from groundcovers and perennials through shrubs and understory trees to canopy trees.

Cofounders Glenn Herlihy and Jacqueline Cramer imagined a food forest as their final project for a permaculture class led by Jenny Pell, using the seven-acre, grass-capped Jefferson Park reservoir as their canvas. Instructors urged the students to bring it to the city government to make this living food bank a reality.

After months of community meetings and negotiations with government officials, they developed the forest, on land owned by the Seattle Public Utilities, with city grant funding under the guidance of the Department of Neighborhoods, who leads Seattle’s P-Patch community gardening program. The City of Seattle stipulated that an umbrella organization help structure the volunteer-run project.

While the initial plan was to have the whole project open forage, this compromise worked on many levels to build a strong foundation for the Beacon Food Forest. The Department of Neighborhoods manages the 25 community plots on-site—some of which are dedicated to food bank donations —and being an official P-Patch enabled insurance for volunteers, covered water costs, and made Beacon Food Forest eligible for city grant funding.

The open harvest piece remained both the most inspiring and troublesome part of the idea. After an intensive grassroots campaign of posters and postcards introducing the project, the first community meeting drew 70 people, the third 120, and then some food activists came on board. That was enough to demonstrate community support, yet the city was concerned about a 24/7 resource unintentionally harboring unhoused people, as well as attracting vandalism or unwanted harvesters like rats. Organizers met with the Seattle Police Department to learn design protocols that included plenty of sight lines. Earning an initial grant of $22,000, the group hired architects and teamed with students at the University of Washington to include a Gathering Plaza for meetings and classes.

“The open harvest policy has been very successful,” said Herlihy. “We haven’t seen negative or detrimental impacts from it. Sometimes a lot of yield will disappear, but that is a sign it’s being used. The more we put in, the more there is for everyone, so it’s working and that has been a surprise for a lot of people.”

“The open foraging policy is our act of food sovereignty,” Herlihy added, “in that we determine what we grow and how it’s distributed. Foraging is also beneficial in not only gathering foods but a connection to the cycle of plants, we learn what is available, when it’s ripe and when harvesting it have a physical connection to the plants.”

The reservoir’s proximity meant the site is “water-quality land,” appending a host of restrictions on the property to protect the water, such as not having restrooms, trash cans, pesticides, or permanent structures. The Beacon Food Forest is not allowed to use raw manure or keep animals.

Building in seven phases, the first phase focused on planting the tree and berry layers, according to the South Seattle Emerald (Robinson 2017). Nuts and fruit tree guilds include apples, pears, plum, quince, medlars, and hazelnuts, with an understory of blueberries, goji, honeyberries, thimbleberries, and aronia. Perennial edibles and medicinals like cardoon, kale, and herbs pepper the plantings throughout.

The media blitz attracted attention around the world, cofounder Jacqueline Cramer recalls.

“Even as the food forest was being installed, people kept requesting to tour it. I remember touring with people from Africa, land-use planners from Holland, and others who came through the Seattle government.” Herlihy and Cramer traveled to several municipalities in Taiwan to share their experiment in urban agroforestry.

The project is centrally located on a highly visible south-facing open slope near a business district, public middle school, high school, daycare centers, and a veterans hospital. The Beacon Hill neighborhood is one of the most diverse in Seattle both ethnically and culturally, with approximately 50 percent of its residents Asian or Pacific Islander, 22 percent Black, and 8 percent Latino. It also has the highest percentage of foreign-born residents of any Seattle neighborhood, at 44 percent, according to the South Seattle Emerald (Robinson 2017).

The neighborhood welcomed the project with open arms—and came ready to use them. Work parties, which often culminated in a communal potluck dinner, regularly drew over 100 volunteers a day. Beacon Food Forest’s popularity helped fuel other local projects too. Some days they had so many they sent extra volunteers to help work at nearby community gardens like El Centro de la Raza.

The second phase, which broke ground in 2019, adds 1.75 acres. It expands existing offerings and increases accessibility on the sloped site to better conform to the Americans with Disabilities Act, with the goal of planting the full seven acres.

Within this space, visitors will find a seed bank with signage in five languages, an herb spiral, a hügelkultur display, native prairie and wetland restoration, beehives, a cardoon forest, a xeriscape demonstration garden, and more. The harvest map sign is on chalkboard, because like any garden, its contents are ever changing.

One major change is after years of being fully volunteer, the Beacon Food Forest became a 501(c)(3) nonprofit in 2019 and was able to hire two staff members. Previously, because of a legal provision preventing public land from earning money, the BFF wasn’t allowed to pay anyone—even instructors or tour guides. Now, it rents a small portion of the land from the city to be able to pay instructors and staff.

The Beacon Food Forest has two staff members, a community relations director, and a site and programs director. The site hosts tours, classes on guilds and agroforestry, school and corporate groups, and soon summer camps.

Cramer, who now works as a schoolteacher in Hawai`i, was excited by the progress she saw when she returned during the pandemic after many years.

“I stopped at the Beacon Food Forest with two grocery bags. I filled them with greens and berries and tomatoes. It was amazing to me. That was the far-fetched dream 10 years prior—that someone could pick a bag of healthy food. It came to fruition literally.”

The pandemic brought some seismic shifts. Meetings went on Zoom, work parties were strictly distanced, people scattered, and the potlucks were canceled. It was an “oasis” for the people who came, said Community Relations Director Priya Diaz, but volunteer numbers dwindled and staff is working to restore them.

Diaz, a former volunteer, said the pandemic also highlighted the need to actively boost food production for the community, especially its most underserved. The forest welcomed community partners and took another look at its mission.

A survey pointed them toward increasing food access fast, Diaz said. “It’s even worse these days with rising food prices in Seattle, so our mission is to make food as accessible as possible.”

Debates arose in committees challenging the original dream versus present-day needs, annuals versus perennial crops, private garden plots versus foraging, and the meaning of “open harvest.” Should they grow different foods? For whom? As a side effect, the organizational structure completely transformed.

“As time went on, the whole organization shifted from centralized to collaborative collective organization, which was pretty interesting,” said cofounder Herlihy, who has taken a less active role in recent years.

“The new side of Beacon Food Forest, this collective idea of land stewardship, is focusing more on annual production and a larger yield of annuals,” Herlihy said.

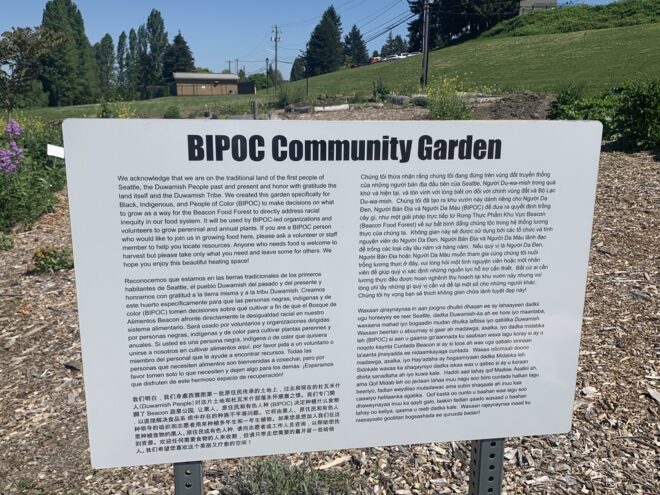

In 2022 a volunteer group built a BIPOC Community Garden (since expanded) dedicated to culturally relevant food for people of color in the community. Percussion Farms tends a plot to share plants and produce with people of color. A group of veterans grows a victory garden.

The Seattle Indian Health Board created a medicinal garden named sust̓əlǰixʷali, Lushootseed for “a place where medicine is created” (Seattle Department of Neighborhoods 2021).

“Different groups took on different parts of the garden and took on autonomy in how they grew it, which was a challenge to the food sovereignty of the project,” Herlihy said. “We wondered, ‘Would these groups still allow public harvest?’ Most did, and at the same time had to find their own way of expressing that either by signage or how they organized their parties. It’s an excellent way of expanding, I think. It’s a challenge but a good one.”

Some groups focus on specific plant groups. Volunteer Tony Dickey, who came to the Beacon Food Forest years ago via a permaculture-loving roommate and landlord, got hooked on feeding pollinators. He started Pollinators Plus, an initiative advocating for all types of pollinators.

“It really is something, even at the university level, that is way underrepresented,” he said. “A lot of the programs on entomology are geared toward pest control, not the betterment and wherewithal of insects.”

Volunteer and landscape restoration advocate David Perasso started a prairie and wetland restoration project that takes up about one-fifth of an acre and recreates native plant communities like camas (Camassia spp.) and wapato (Sagittaria latifolia). Volunteer Antonio Flores now manages the restoration project.

“We definitely face challenges,” he said. “A lot of them are from introduced species. We get a lot of weeds and a lot of browsing pressure from the nonnative Easter cottontail rabbit.”

When we spoke, Flores was expecting his first camas harvest.

“The challenge is the world has changed since the time these plants were thriving,” he said.

Striking a balance between the needs of the land and the needs of the people is a common theme echoed by the volunteers we spoke with.

It’s Not Just the Food

“Even though we are growing food here and we’re trying to feed people,” said Diaz, “a big part is growing a space for healing, especially an affinity space for people of color in the BIPOC garden. It’s a place of context, so people can figure out how to live in harmony with the world among different cultures. It’s not just about food.”

Sometimes, it’s about meeting an innate need that is still dormant.

“Healing is a big part of the magic for people who don’t realize they need it,” Herlihy agreed. “They find flowers or herbs or it just feels bountiful, and then they feel in their souls they just need to be there.

“People who don’t have yards have found they do need to see where their food comes from. They need to have a connection to some land, and they find a community all about sharing and foraging for food, and that just hooks them in.”

While the gift of free food may have been the initial news, the true gift of the Beacon Food Forest may be something else. Every person stressed the power of community as the fuel behind this project’s enduring momentum.

Cramer was asked to speak recently on sustainable building and disaster preparedness.

“When I presented about Beacon Food Forest, I said, ‘If catastrophe hits, those pears will be gone.’ The lesson is not that it has a bunch of food there, it’s that people learned to work together. We found a way to see what we had in common.”

Growing, together and separately, in and out of the garden, seems to be the path forward.

Resources

Beacon Food Forest contains a patchwork of gardens, including Percussion Farms and the Seattle Indian Health Board medicinal garden, sust̓əlǰixʷali.

For more information about community garden resources in and around Seattle, see Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods and Seattle’s P-Patch Community Gardening Program, and El Centro de la Raza.

Mellinger, Robert. 2012. Nation’s largest public Food Forest takes root on Beacon Hill. Crosscut. February 15, 2012.

Robinson, Chetanya. 2017. Beacon Hill’s Food Forest Seeding Change in the World. South Seattle Emerald. May 31, 2017.

Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. 2021. Native American Heritage Month: Seattle Indian Health Board Traditional Medicine Garden. Front Porch. November 24, 2021.

Read Pacific Horticulture’s 2013 Beacon Food Forest article by Logan Bingle

Responses