Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Located in Southeast Seattle, Beacon Hill is a culturally diverse neighborhood that’s uniting behind a horticultural experiment. Breaking away from a traditional community garden model with separate beds tended by individuals, gardeners at the Beacon Food Forest are combining their efforts to create the nation’s largest edible forest based on permaculture ideas. It’s an exciting collaboration developed by a new generation of environmental leaders and thinkers.

In 2009, Glen Hurley was taking a Permaculture Design Course (PDC). The class followed a standardized format developed by the Permaculture Institute to teach students about the practical applications of permaculture. At the same time, Hurley was volunteering on the planning committee for the new Jefferson Reservoir Park, a new city park topping an old reservoir. Hurley saw an opportunity to transform a grassy slope on the park’s western edge into a food forest using the concepts taught in the PDC. Hurley and a team of like-minded students developed this vision into a proposal and schematic design for their final project.

Inspired to elevate their vision to the next level, Hurley and other students formed the Beacon Food Forest Committee. The committee was awarded $20,000 by the City of Seattle to study neighborhood interest and develop a design. Margaret Harrison was hired as landscape architect along with Jenny Pell, a permaculture consultant. Three neighborhood meetings held in 2010 were well attended and demonstrated strong support for the project.

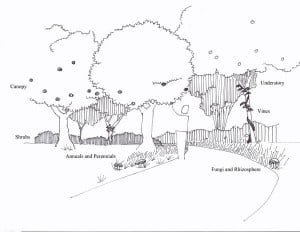

The plan is to grow food in a manner similar to a forest ecosystem, with seven layers of edible plants: canopy, understory trees, shrubs, vines, perennials, annuals, and fungi. In addition, plants will be selected based on guild affiliations; self- sufficient plant communities such as nitrogen-fixing plants will be placed next to plants that are heavy nitrogen feeders. The students drew inspiration from the historic savanna management practices of the Kalapuya peoples in the Willamette Valley, and food forest projects developed by Richard Walker in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Harrison and Hurley noted that a particular challenge faced by the design team was selecting which plants to include in the forest. Due to the cultural diversity of the neighborhood, each resident wanted fruits and berries native to their homeland. The plant list ranged from the expected, such as blueberries and raspberries, to more exotic fruit including goji berries (Lycium) and honeyberries (Lonicera caerulea). This led to the creation of a food tree arboretum as part of the project to exhibit unusual fruit trees that can grow in Seattle.

With feedback from the community, Harrison Design developed a schematic design for the seven-acre site that the Beacon Food Forest Committee used to request further funding from the city. In 2011, Seattle awarded the Food Forest Committee $100,000 from surplus funds to develop construction documents and begin building. Because of challenges with the land being held by Seattle Public Utilities, the Beacon Food Forest will be built in phases. Phase one construction, covering two acres, will include an orchard, play area, garden center structure, and traditional community garden (P-patch) space. It is hoped that early success will allow the Beacon Food Forest to continue expanding its operations over the remaining five acres.

On November 17 and 18, 2012, the Beacon Food Forest and City Fruit—a local program working to educate people about fruit tree care—held a work party to sheet mulch the area that will become the orchard and plant trees and shrubs, including blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), plums (Prunus spp.), fresh eating and cider apples (Malus spp.), pears (Pyrus spp.), heartnuts (Juglans ailantifolia), and butternuts (J. cinerea). City Fruit also provided a series of presentations focused on the planting and care of fruit trees during and after the work party for participants and community members. They also discussed how to harvest and use fruit once trees begin producing. City Fruit and the Beacon Food Forest Committee hope participants will use these skills at home on fruit trees they already have or might plant on their properties.

In March 2013, Harrison and the Food Forest Committee began working with Conservation Corps, a program that provides work and educational opportunities for disadvantaged groups such as ex-convicts, the homeless, and unemployed. Together the team constructed a series of cedar timber and recycled concrete terraces on the site, which are designed to retain the hillside and support the traditional P-patch, play area, and garden center.

Architecture students from the University of Washington also met with volunteers and the Food Forest Committee this past winter and spring to design and fabricate a shelter and surrounding plaza. The process provided the students with the opportunity to apply their design skills and the resulting structure will serve as a gathering space in the garden for work parties and classes.

With work well underway, the Beacon Food Forest continues to push into the future. Work parties recently began developing the orchard’s understory with shrubs and legumes, and development will begin on the play area and P-patch area. The Beacon Food Forest will test new horticultural ideas, inspire environmental leaders, and bring together the diverse community that is Seattle’s Beacon Hill Neighborhood.

For more information and to connect with the Beacon Food Forest, check out the website at www.beaconfoodforest.org.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Healing Gardens

Spring 2022 Emily Murphy believes gardens hold the key to saving our health, our communities, and our planet. In her new book Grow Now Murphy

Your Keystone Plant Matrix with Garden Futurist Doug Tallamy

Spring 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XIV podcast here. If you take Keystone plants out of your local food web, the food

A Botanical Force

Listening to Alice Doyle recount the origin stories of Log House Plants’ most popular introductions, educational campaigns, and innovative collections is a great way to

Responses