Native Bees and Your Garden

Contributor

Winter/Spring 2023

The native bees in and around our gardens face ever-increasing environmental pressures as they carry out their pollination duties. More than a quarter of all North American bumble bee species are at risk, according to the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Land loss is one of the leading causes of the decline in native bee species, and we can all easily do something to help. Growing native plants doesn’t just help native bees, it restores habitat for birds, butterflies, and many more creatures.

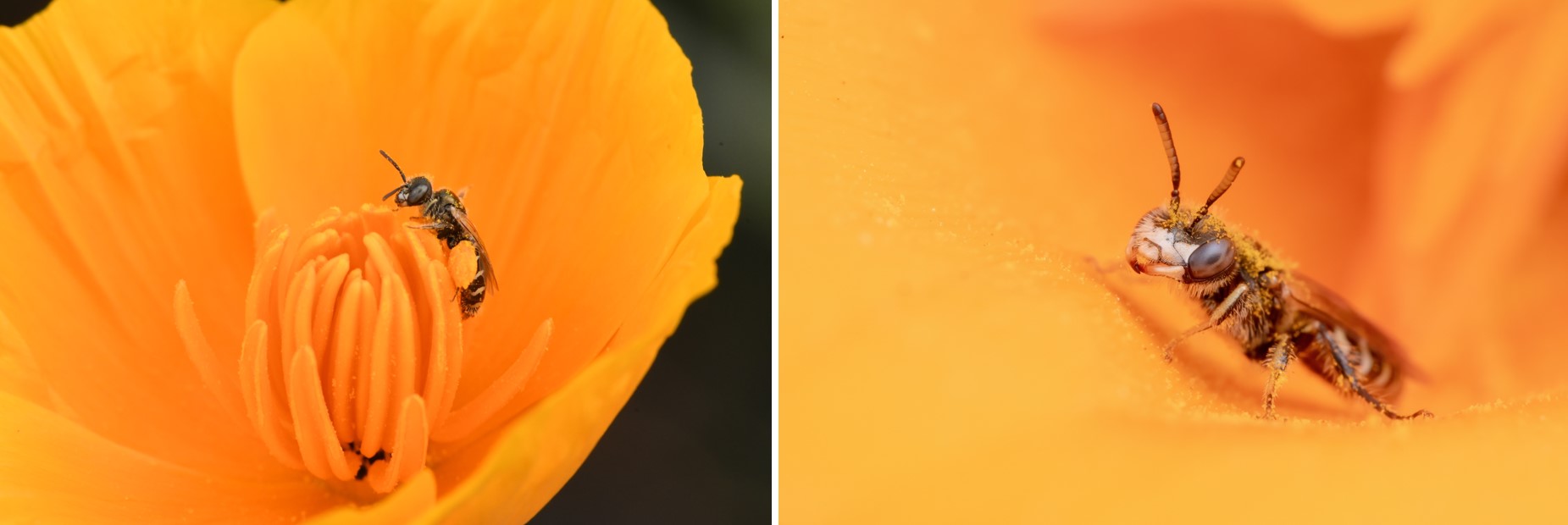

Due to my conservation work, I am frequently invited to people’s homes to look at their native gardens and photograph any bees present. One of my favorite gardens to visit is in Altadena, California. It’s a beautiful acre full of colorful native plants, chickens, and two children with extensive ecological knowledge. On my first visit alone, I photographed and observed eight species of bees. One of which turned out to be a California poppy fairy bee (Perdita interrupta) which, up until that point, I’d never had the luck to see in person. This rare bee can be found during April and a few days into May. This fairy bee has a symbiotic relationship not only with California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) from which they collect pollen, but also collects nectar from popcorn flowers (Cryptantha). Each year I’ve visited this garden, there has been a significant and stable population.

Right: California poppy fairy bee male on California poppy. Photo Credit: Krystle Hickman

Not only that, but after I my first visit, one of the homeowners took photos of Crotch’s bumble bee (Bombus crotchii) in her garden, one of California’s four endangered bumble bees. So far, I’ve documented the genera Perdita, Bombus, Eucera (Peponapis), Osmia, Agapostemon, Halictus, Lasioglosum (Dialictus), and more, totaling more than 15 species of bees all at this one location.

Native bees made me reconsider what a garden could or should be. Native bees are native to where they currently reside, separate from human introduction. They can be native to the United States, a single state, or even an area as small as a zip code. These bees thrive alongside native plants. Which, just like native bees, are native to where they currently reside. Native bees and native plants can have mutually beneficial relationships called symbiotic relationships, where one or both rely on the other to survive. Saving the bees also means saving the plants. For most people, the first bee that comes to mind isn’t a native one; it’s a honey bee. Since honey bees aren’t native to the United States, they don’t have mutually beneficial relationships with the native plants here. They’re fine visiting the manicured non-native plants in our yards. Meanwhile, lawns often lack plant selections that make the most of native bee relationships

A benefit of having a native garden is there is little to no need for pesticides or herbicides. While these products are an easy way to get rid of unwanted plants and insects, they harm more than just their intended targets. For example, a pesticide that impacts the California poppy fairy bee could leave poppies unpollinated. An herbicide targeting the poppies could leave the fairy bee without pollen. Poisons have unintended targets traveling up the food chain and throughout the environment. A healthy native habitat will naturally keep a stable balance between plants, insects, and the rest of the food web.

How do you know you have a healthy native habitat in your garden? Look for insects that I like to call indicator insects. These insects indicate the presence of a healthy biodiverse ecosystem. Their existence relies on a population of creatures a lot of us consider pests. They are living pest control. An aphid mummy wasp (Aphidiinae) is an example of one of these creatures. They’re small, usually not exceeding 1.5 millimeters, and easy to miss.

Right: Aphid mummy wasp male next to a quarter. Photo Credit: Krystle Hickman

These wasps are parasitoids of aphids. A female will oviposit—insert—an egg into the body of a live aphid. The egg will hatch, and the larvae will develop, consuming the aphid from the inside and causing the aphid’s body to swell as the wasp grows. This process kills the aphid. When the wasp is ready to eclose—exit—the aphid, it will chew its way out and emerge as an adult.

Right: Deceased aphid. Photo Credit: Krystle Hickman

People may be more familiar with another indicator insect, lacewings. Lacewing larvae consume aphids, mealybugs, spider mites, leafhopper nymphs, moth eggs, scale, thrips, and whiteflies.

Right: Lacewing larva. Photo Credit: Krystle Hickman

These are just two of many indicator creatures. Others include spiders, lizards, or even birds. To maintain a healthy biodiverse ecosystem in our gardens, we can’t pick and choose which native creatures we keep, just as we cannot remove wooden blocks in a game of Jenga and hope the tower will forever continue to stand.

Once you have native plants in your garden, you can help native bees thrive in the habitat you’ve created. Mulch is beneficial because it looks great, retains water, and reduces weeds. However, since 70 percent of native bees are ground nesting, areas with thicker mulch can act as a deterrent. Consider maintaining a mulch-free zone around the base of plants that bees and other pollinators are visiting. Six to twelve inches around these plants is enough room for ground-dwelling bees to nest in. Instead of mulch, consider leaving the leaves in your garden. Leaves provide valuable organic matter to build up healthy soil. Healthy soil is biologically diverse, with creatures like earthworms, bacteria, arthropods, and fungi inhabiting it. Leaves work as weed suppression and moisture retention while creating a warm blanket for overwintering animals such as bees, butterflies, and wasps.

Thirty percent of bees are cavity nesting, meaning they’ll nest in holes in wood or plant stems with pithy centers. To support these bees, instead of completely removing plants, leave 12–18 inches of the stem to nest in. The plants that work best have long, linear, strong flower stalks with varying diameters. These cavity-nesting bees are also the ones likely to use beehouses.

Beehouses are not necessary in a native garden. However, if you want one, ensure the cells in which the bees reside are at least six inches deep and can be easily cleaned. Like any stable or doghouse, beehouses must be cleaned to keep out pests and disease. There are tutorials on YouTube that provide step-by-step processes for cleaning your beehouse. Also, I’d recommend purchasing a beehouse with a drawer for holding bee cocoons after they are cleaned. Female bees typically lay male eggs closer to the entrance of their burrow, which is why males are typically smaller than females and emerge as adults first. Placing the cleaned cocoons in a drawer instead of back in the beehouse cells can ensure the adult bees emerge as they’re supposed to.

There is a common misconception that providing water for bees is beneficial. If you currently have a water source for bees, observe what type of bee is visiting. Water sources are not needed for native bees. Native bees get all their hydration from plants. As far as bees go, shallow water sources will only attract honey bees. All honey bees in the United States are non-native farm animals and are invasive. Typically, honey bees in a garden will out-compete native bees for resources. They also are known to spread deformed wing virus to bumble bees through infected pollen.

Besides creating a native habitat in your garden, kindly encourage the people around you to do the same. If future homeowners replace gardens with lawns, neighbors with even a small native habitat can provide a bridge for these beautiful creatures to travel along and thrive in. Honey bees are known to travel two miles from their hives in search of resources, but the same can’t be said for native bees. Some nest right under the plant they pollinate.

Nature doesn’t have to be a place we travel to. We can spend time in our gardens and immerse ourselves in nature, watching the changing seasons, the comings and goings of creatures, and the blooming of flowers. Our gardens can be beautiful habitats that should be appreciated not only by us, but the creatures with which we share this world.

Resources

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation includes pages on both at-risk bumble bees and other at-risk bees.

IUCN Bumblebee Specialist Group

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Voices of the West; New Science on Life in the Garden

Did you know that oaks can harbor over 800 species of insects? That includes only those feeding directly on oak, where they feed on every

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Growing a New Generation of Farmers, One Plot at a Time

Summer 2022 Duane Lane, a Yakama tribal descendant, spends his weekdays working in Portland as a resource navigator for the Oregon Native American Chamber of

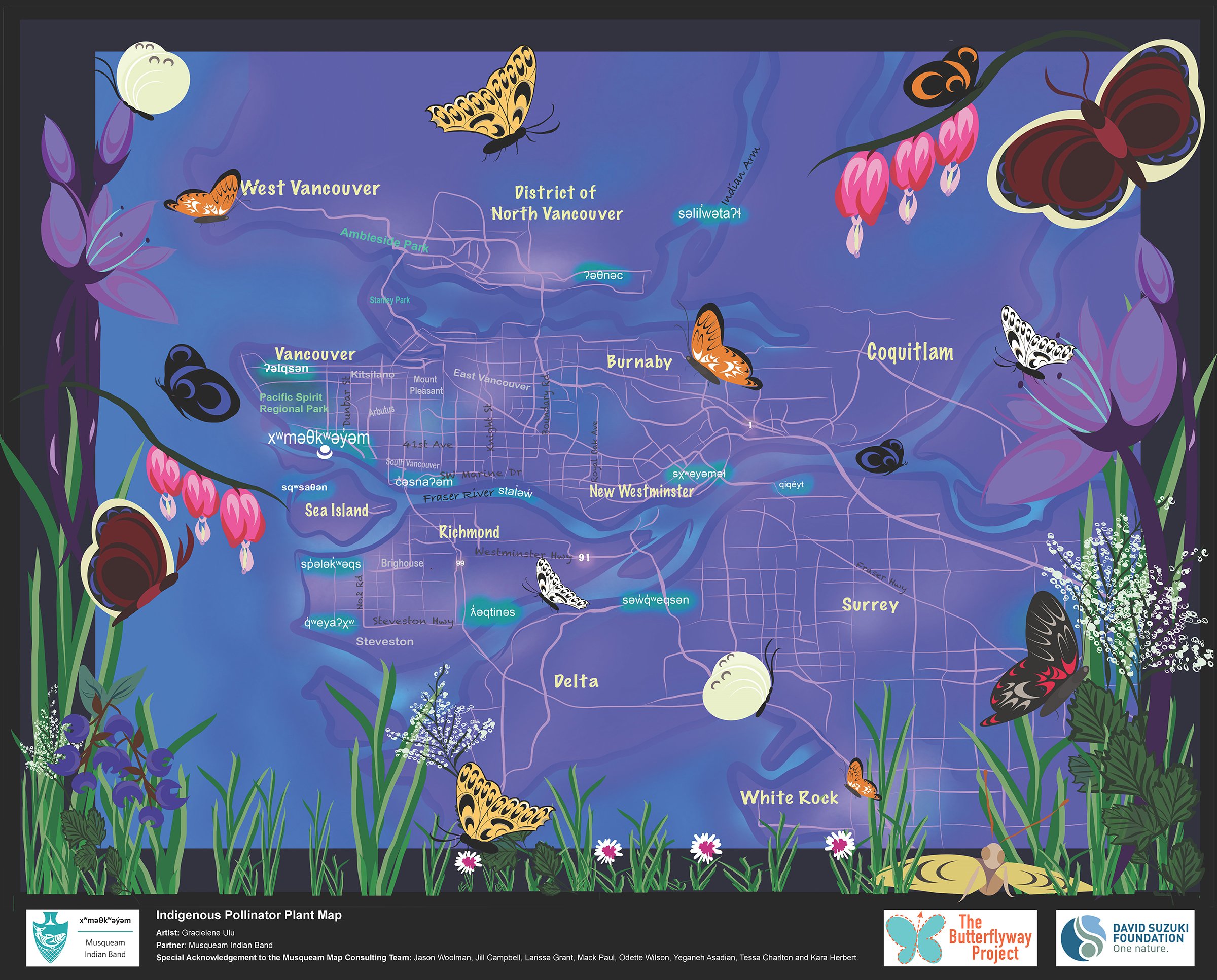

Musqueam Indigenous Pollinator Plant Map

Spring 2022 Apart from helping pollinators like butterflies and wild bees, the Butterflyway Project started in 2017 to explore the relationship between indigenous plants and

Responses