Contributor

Summer 2021

Watch our Landscapes of Change video about The Potrero Hill Eco-Patch here.

Introduction

Native, biodiverse, and ecologically functional planting creates a foundation for resilient ecologies in the face of anthropogenic mass extinction. Yet we cannot rely on conservation land alone to perform this role; protected areas are too small and too fragmented (Tallamy 2020). We need to look to our cities, suburban areas, gardens, parks, and leftover spaces to fill the void. Recognizing this, the need for functional planting in urban landscapes is steadily growing, both in high visibility spaces like roof gardens and parks, and in the underutilized fragments of urban land such as utility easements (Rainer and West 2016). Home gardens are also becoming biodiversity hotspots as residents become more attuned to their potential role as land stewards.

However, in our experience at the landscape architecture practice Field Collective, working with plants native to California presents unique challenges. Typical aesthetic expectations of planting in public or semi-public spaces—tidy, static, and evergreen—are often at odds with the periods of dormancy and deciduous nature of many California plants. We believe the ability to experiment with regionally native species, mixes, and spacings is fundamental to bringing ecologically functional planting into conventional urban landscape architecture projects and home gardens. There are compelling precedents for this type of work in the East Coast, the UK, and Europe that demonstrate there is an opportunity to scale up efforts.

The opportunity for us to advance our work with native planting began when we volunteered our services to the California Native Plant Society (CNPS). A group of Potrero Hill neighbors—consisting of folks from the Dogpatch and Northeast Potrero Green Benefit District (GBD) and from the CNPS Yerba Buena Chapter—had discussed building a San Francisco native plant demonstration garden for their neighborhood. In early April 2020, we led the design and volunteer-coordination process of the Potrero Hill Eco-Patch, taking the first step in our vision to rewild the urban landscape of California.

Ecologically functional planting in urban environments

In Switzerland and Germany, mixed perennial plantings refer to plant mixes developed through rigorous research then widely applied to landscapes in the public realm (Oudolf and Kingsbury 2014). Mixes are developed for specific growing conditions, aesthetic criteria, and ease of planting and maintenance. Similarly, at the University of Sheffield in the UK, Nigel Dunnett, James Hitchmough, Noel Kingsbury, and colleagues experiment with the development of artificial plant communities by applying “a knowledge of plant ecology to ornamental horticulture” (Oudolf and Kingsbury 2014). In the United States, Thomas Rainer and Claudia West’s Planting for a Post Wild World outlines a design process using specific plant designations of structural, seasonal, filler, and groundcover planting in specific percentages to create successful biodiverse and naturalistic plantings (Rainer and West 2016). We believe there is an opportunity to do similar plant mix research in California using regionally native planting.

According to the Centre for Biological Diversity, the “San Francisco Bay Area is one of the nation’s six most important biodiversity hotspots” (San Francisco Bay Area and Delta Protection). There are over 400 documented plants native to San Francisco (Wood 2014), and yet they are vastly underused in ornamental horticulture applications around the city. The dormancy and deciduousness of California plants, often in part a result of their adaptation to our summer dry climates, can make them challenging to incorporate. However, their increased use is critical if we are to transform our urban and suburban landscapes into patches of biodiverse and resilient habitat. Specialized relationships between plants and insects are vastly more common than generalized relationships (Tallamy 2020), meaning most insects have very particular needs met only by the local plants with which they co-evolved. For example, the mission blue butterfly (Icaricia icarioides missionensis) is particular about silver lupine (Lupinus albifrons) and summer lupine (Lupinus formosus) as host plants. Because of reasons including habitat loss and fragmentation, this butterfly is federally listed as endangered (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2017). If we wish to increase the native insect population, we must include their host and nectar plants more often in our projects and gardens. The unification of aesthetic preference with biodiversity enhancement is the cornerstone of the Eco-Patch test garden.

The Eco-Patch, Potrero Hill, San Francisco

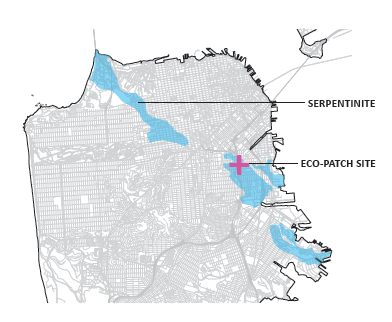

The Eco-Patch is sited on Caltrans property adjacent US Route 101, along Vermont Street between 17th and Mariposa streets. A swath of serpentinite, which runs through San Francisco, underlies the site (Sloan and Karachewski 2006). This offers a unique ecology for plants adapted to, and tolerant of, serpentine soils and the wildlife that have coevolved with them.

Areas in the Presidio to the north and San Bruno Mountain to the south share this unique geologic context, but because it is relatively rare, many of the plants and wildlife that evolved in serpentine ecologies are now endangered. The Presidio manzanita (Arctostaphylos montana ssp. ravenii) is one such plant, with only a single wild plant documented in a serpentine rock outcropping in the Presidio of San Francisco (Davison 2018). Wildlife, such as the bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha bayensis), depend on plants, such as dwarf plantain (Plantago erecta) and owl’s clover (Castilleja exserta), that grow in serpentine soil (Davidson 2018). For the bay checkerspot butterfly and other wildlife that depend on native, serpentine-adapted plants, urban habitat fragmentation is a major threat.

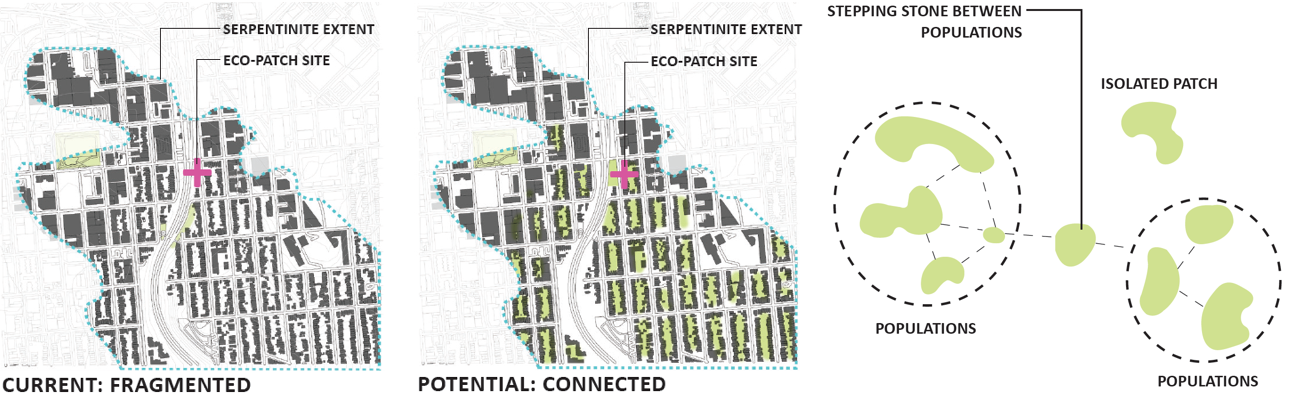

The name Eco-Patch refers to the patch-corridor-matrix model in landscape ecology (Forman 1995). Our goal is to inspire a proliferation of patches featuring plants adapted to and tolerant of serpentine soils, thereby increasing habitat connectivity between serpentinite ecologies and mitigating the impact of biodiversity loss due to urban habitat fragmentation.

The patch-corridor-matrix model is pertinent to home gardeners as well. The typical framework for property development at the block scale includes numerous adjoining backyards, separated only by hedges or fences that form no barrier to bees, butterflies, and birds. In this context, home gardeners who plant with natives can become citizen activists who hold significant power to improve their neighborhood’s biodiversity and ecological resilience. Whether gardeners coordinate within a block, between a couple of properties, or independently, when combined their gardens can create multiple habitat patches or even whole habitat corridors.

Center: A connected native patch network, achieved through the community planting native habitat in their own backyards.

Right: If enough habitat patches are restored in proximity to one another, many species, especially insects and birds, can island hop and reestablish—particularly if there are corridors connecting them.

For the Eco-Patch, we aimed to design a plant mix that: 1) is native to San Francisco; 2) will provide habitat and food supply for local native insects; 3) is visually and experientially engaging enough to encourage neighborhood adoption of the plants into backyards and other greenspaces; and 4) will meet the objectives of both CNPS and GBD community groups while also gaining approval from Caltrans and the San Francisco Department of Public Works.

Building on the idea of the Swiss and German mixed perennial plantings, the Sheffield School of Planting, and the work of Claudia West and Thomas Rainer, we designed the Eco-Patch Test Garden. The 900-square-foot test garden allows us to test, through implementation and monitoring, different planting mixes composed exclusively of plants native to San Francisco. In addition, we are testing three different non-herbicide weed management approaches: 1) sheet mulching (a combination of compost, cardboard, and wood mulch); 2) sheet mulching combined with the use of filler species (seeded plants we test for competitive advantage against weed species that proliferate in gaps while the planting is establishing); and 3) solarization (a method used in organic farming involving “baking” weed seed under a layer of plastic).

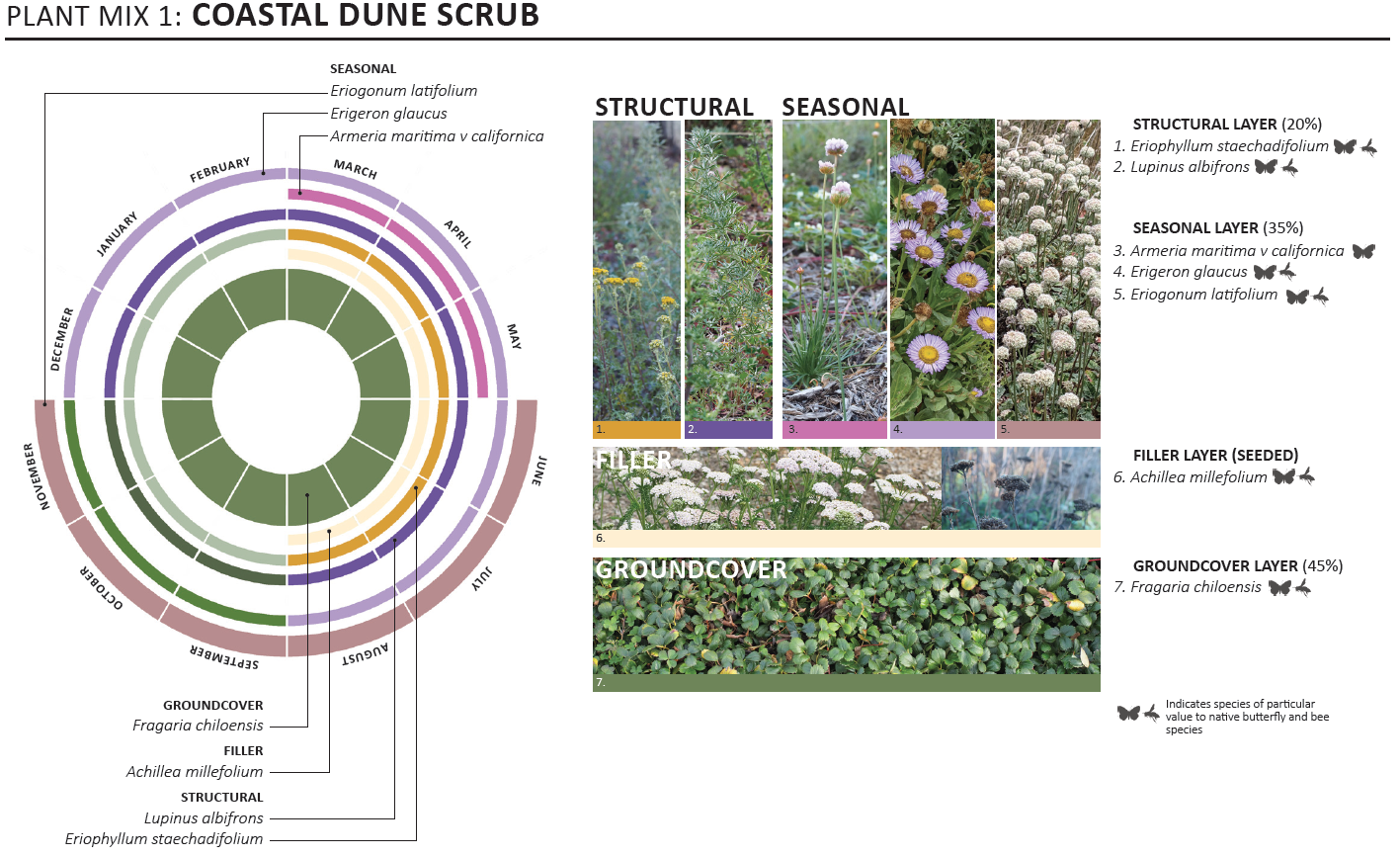

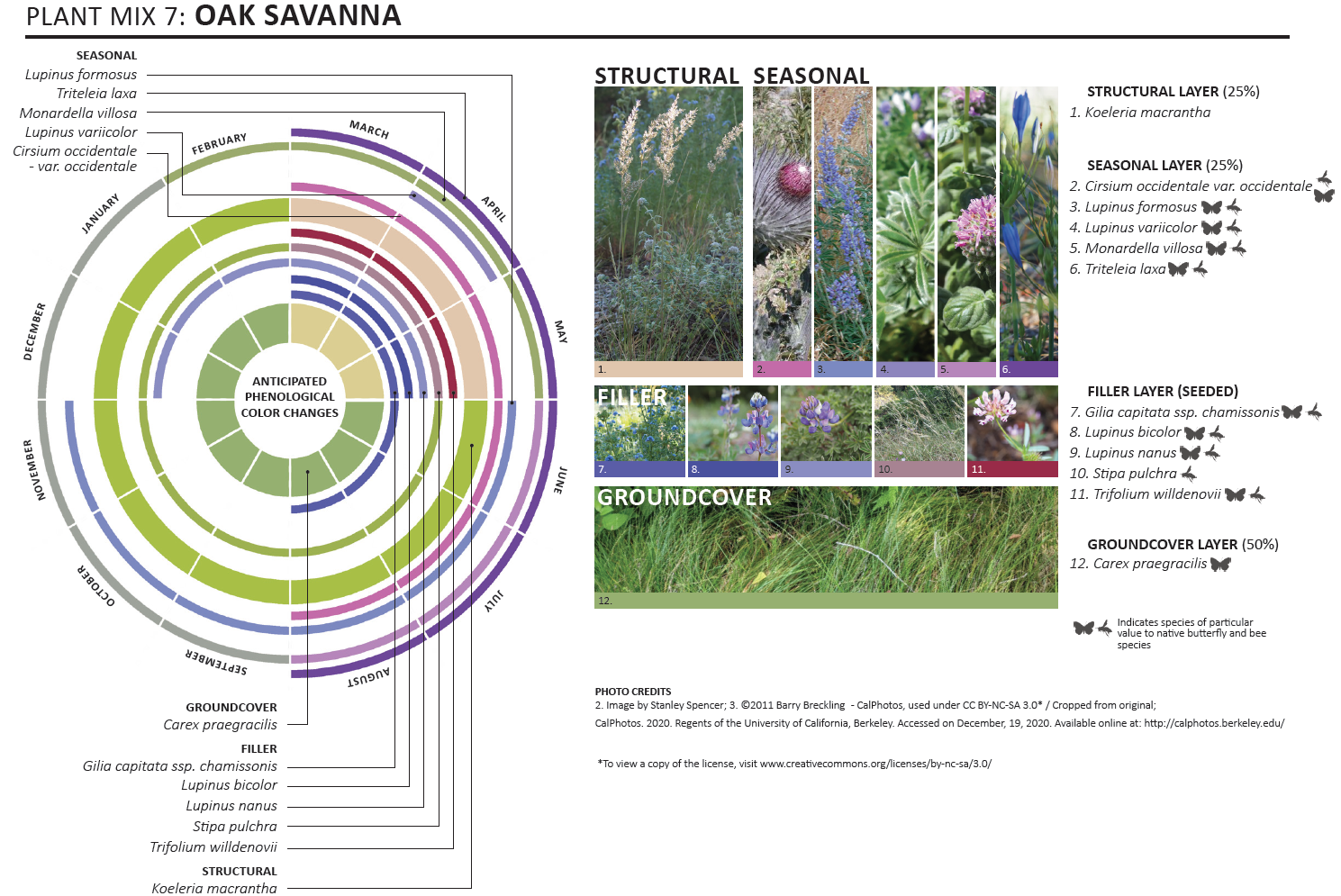

Before we designed the plant mixes, we identified various landscape archetypes that likely previously existed either within or close to San Francisco, such as “oak savanna” and “coastal dune scrub.” We wrote a planting design statement summarizing how we could distill and amplify the essence of those landscape archetypes. We then categorized each potential plant for testing as a groundcover, filler, seasonal, or structural plant, using Rainer and West’s (2016) descriptions of these categories as a guide.

Next, we composed eight plant mixes, creatively synthesizing our landscape archetype analysis with the categorized species list to ensure a dynamic layering of plants. We then calculated the plant percentages and quantities of each mix and used this to design a square layout module specific to the mix. An advantage of modular plantings is each module can be laid out on a grid and repeated as many times as needed to fill the space. We repeated each mix’s module three times: one module for each weed management strategy.

Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. Accessed on December 19, 2020. Available online at: https://calphotos.berkeley.edu/

Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. Accessed on December 19, 2020. Available online at: https://calphotos.berkeley.edu/

In July 2020 site preparations began in earnest; a combination of volunteers and paid contractors sheet mulched 16 of the 24 test plots to begin the first phase of our weed control testing. In September, a group of volunteers installed the solarization plastic. Volunteers planted the 24 plots during multiple workdays in late November and early December 2020. For the sheet-mulched plots, we planted directly into the ground through the mulch. Before planting the solarized plots, we cleared the plastic away and removed the weeds that had sprouted under the plastic.

The plants, each labeled with a bright pink flag, started to grow almost immediately. Come April 2021, the garden was humming with life and taking shape beautifully. The different plant layers we designed were becoming more visible and the constant buzzing of bees was wonderful.

Since then, we’ve had successes and setbacks. From the beginning, the garden has relied on water from a generous neighbor whose property is adjacent to the Eco-Patch. However, in late May for a period of several weeks, the neighbor was temporarily unable to continue the supply—a calamity for any establishing garden but particularly problematic during a severe drought. Thankfully, the garden was given a slight reprieve by the GBD, who helped to the extent possible, and by the passionate actions of neighbor and Eco-Patch advocate Jean Bogiages. With support, she carted water to the site in her car and used a 30-gallon motor-driven pump to disperse it.

The neighbor eventually was able to supply water again, but the garden will likely not recover its vitality until spring 2022. The experience was a sobering reminder that even drought-tolerant natives still need reliable water while establishing.

To Be Continued – Read Part 2: Preliminary successes and recommendations

Resources:

Calscape (run by California Native Plant Society) is an incredibly in-depth database and tool for learning about plants native to California—invaluable for planning native gardens.

Find Eco-Patch on iNaturalist at Potrero Eco-Patch Monitoring Area.

California Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2014. Presidio Manzanita.

California Native Grasslands Association. 2021. Grassland Facts.

California Native Plant Society. 2018 Sheet Mulching.

Davison, V. 2018. Bay Checkerspot Butterfly – Invertebrates, Endangered Species Accounts: Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office.

Forman, R. T. 1995. Land mosaics: The ecology of landscapes and regions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oudolf, P. and Kingsbury, N. 2014. Planting: A new perspective. London, OR: Timber Press.

Rainer, T. and West, C. 2016. Planting in a post-wild world: Designing plant communities that evoke nature. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Center for Biological Diversity. San Francisco Bay Area and Delta Protection.

Sloan, D. and Karachewski, J. 2006. “Chapter 5 San Francisco: Geology Beneath the Pavement” In Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tallamy, D. W. 2020. Nature’s Best Hope: a new approach to conservation that starts in your yard. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

University of California Integrated Pest Management. Soil Solarization for Gardens & Landscapes Management Guidelines.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Mission Blue Butterfly – Invertebrates, Endangered Species Accounts | Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office.

Wood, M. 2014. Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of San Francisco’s Natural Areas, 2nd ed.

Nurseries we worked with for our project:

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Native Bees and Your Garden

Winter/Spring 2023 The native bees in and around our gardens face ever-increasing environmental pressures as they carry out their pollination duties. More than a quarter

Voices of the West; New Science on Life in the Garden

Did you know that oaks can harbor over 800 species of insects? That includes only those feeding directly on oak, where they feed on every

Expand Your Palette: Waterwise Plants for your Landscape

There’s nothing more thrilling to plant lovers than discovering new plants to test in the garden. Here in the southernmost corner of California, we have

Responses