Turf Transformation into Beautiful, Sustainable, and Resilient Landscapes

Contributor

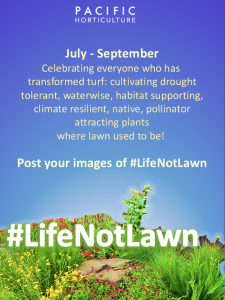

#LifeNotLawn

Climate chaos, continuing drought, extreme temperatures, declining populations of songbirds and insects— are calling for homes and yards that are heat tolerant, water thrifty, fire resistant, and supportive of the local ecosystem. If that overwhelms your to-do list, Pacific Horticulture wants to help! We want to feature gardens designed to meet these needs and invite you to join us.

Climate chaos, continuing drought, extreme temperatures, declining populations of songbirds and insects— are calling for homes and yards that are heat tolerant, water thrifty, fire resistant, and supportive of the local ecosystem. If that overwhelms your to-do list, Pacific Horticulture wants to help! We want to feature gardens designed to meet these needs and invite you to join us.

Some say lack of sustainability is the fault of our lawns, those water guzzling, ecological deadscapes with few redeeming qualities besides being green. Many people are still attached to a smooth, green lawn, a status symbol of their success and a badge of subscription to the English landscape aesthetic. However, we don’t live in Great Britain with summer rain, and in the often hot, summer-dry climate that covers much of the West, lawns don’t make sense. As the human population has expanded, bringing concurrent pressures on resources such as water, a new vernacular has arisen. New values highlighting green living, sustainability, and awareness have changed many minds on what makes beautiful, and appropriate, gardens.

Managing our impact on the watershed

Water supplies in the West depend upon winter rain that is stored as snow in mountains or in reservoirs behind dams. During drought, storage diminishes, and shrinks more each year as drought continues. Maximizing use of this ephemeral resource is critical to the success of our society and its future.

Creating landscapes that require less water reduces consumption and our impact on the water supply. Rainwater harvesting also captures water that can be stored on site in tanks or detained and reabsorbed into the soil to recharge groundwater supplies. If adding a rainwater tank to your yard is beyond reach, simple landscape design can help to direct, detain, and retain rainfall to slow flows and allow water absorption on site. Rain gardens encompass a wide variety of options to slow and absorb water. For examples of options and techniques you can apply at home, see “Soak Up the Rain: Rain Gardens” (Environmental Protection Agency 2021).

What does this have to do with your lawn? There are lower-water species of grasses that can replace traditional, cool-season grasses. Buffalo grass (Bouteloua dactyloides), Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon), sedges ( spp.), and others can lower irrigation needs when used as turf. But if you don’t actually use your lawn for play, entertaining, or pets, removing it can further reduce water use. “Replacing a lawn with a mix of trees, shrubs, groundcovers, vines, and herbaceous perennial plants that creates a nearly complete, well-performing plant canopy over the landscape can be expected to have 50% less water demand than a cool-season lawn” (University of California 2021).

Monocultures versus diversity in the Landscape

Lawns are basically a monoculture, a term taken from agriculture, meaning the planting of only one species over a large area. The problem with these kinds of plantings, whether in an agricultural field or your front yard, is that with only one plant species, there are fewer other organisms. In areas that still possess some of their natural wild vegetation, by removing these areas we remove the complex web of soil organisms, invertebrates, vertebrates, and effectively create a biological desert.

A monoculture’s ability to endure stress is weakened by its lack of checks and balances against pathogens, pest invasion, and root health, which leaves it open to failure and environmental disaster. Diverse plantings provide a bulwark against failure of the entire system from stress and support a much larger set of associated organisms—leading to greater diversity. If a pest attacks and kills a single species, the other species present (which are different enough to not be susceptible) remain and provide options and continue the system. These ecological principles work in large natural ecosystems as well as our urban landscapes, even your front yard.

What plants should we use in our landscapes

Dr. Douglas Tallamy (Homegrown National Park 2021) and others want us to trade in our turf for a diversity of plants and techniques that go beyond eye candy for your home and function in the context of surrounding woodlands, forests, savannahs, and riparian areas.

Smart plant choices and combinations help, especially using drought-adapted native plants that connect your garden with wildlands around you. Both native and non-native plants (Frankie et al. 2014) can provide support to insects and are the base of a food web of pollen and nectar supporting pollinators and their predators. The insects in turn are food for birds and can provide critical pollination services for wild areas and gardens alike.

Native plants often have root systems that grow deeper than those of turfgrasses. In the wild these plants can’t count on sprinklers during a dry spell. To survive over the millennia, some plants evolved deep roots to better tolerate periods of stress caused by heat and lack of moisture. Deep-rooted plants can mine a larger volume of soil for water and minerals and some even reach water tables belowground. They may also possess wide-spreading roots, allowing them to better compete with neighboring plants. Deep roots create larger root masses and growing evidence indicates they deposit considerable amounts of carbon in the soil (Pierret et al. 2016).

Native and compatible non-native low-water plants also may possess physical characteristics like small leaves, spines instead of leaves, and waxy or hairy surfaces that reflect light and reduce leaf temperature—reducing water needs. Other species have internal mechanisms that minimize water loss during transpiration and some, such as our California buckeye (Aesculus californica), go so far as to drop all their foliage and go dormant in the dry season.

Building a Culture of Sustainability

The pandemic brought home the need for each of us to have nature and the outdoors in our lives. People engaged with their gardens in greater numbers and found the healing effects of plants and gardens. Some shared these lessons by designing turf-free front yards, growing food, providing for pollinators, and working with neighbors to ensure that their needs were met. Those of us lucky enough to have parks and greenbelts in our communities could escape our confines and find places that provide shared areas of turf for play and nature for relaxation. A beautiful, dynamic garden provides a model to neighbors and invites engagement in community, to share what we learn and to demonstrate our values.

If we are to live in a changing future, we must choose plants that can live with less water, design our gardens to collect and store precious rain, and grow our concept of beauty to include other creatures that share the world with us. By building your garden’s diversity, you create options for other creatures, provide food and refuge from predators, and create a place to raise future generations. Your garden becomes habitat for wild creatures.

Successful plantings will provide the evidence needed for others to create higher quality gardens, greenbelts, and neighborhoods that will link together in a quilt of plants and create an environment filled with diversity of movement, sound, and color—all the signs of Life.

Please join us in sharing your beautiful and sustainable models for others to see and then head out to the garden, it’s alive outside!

Resources:

Pacific Horticulture’s #LifeNotLawn Campaign Resource Page

Homegrown National Park, Why is Reducing the Area of Lawn Important?, published March 29, 2021.

University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Questions & Answers About Drought & Water Conservation, accessed July 15, 2021.

Environmental Protection Agency, Soak Up the Rain: Rain Gardens, updated July 12, 2021.

Frankie et al. California Bees and Blooms. (Berkeley: Heydey, 2014).

Alain Pierret et al. 2016. “Understanding deep roots and their functions in ecosystems: an advocacy for more unconventional research.” Annals of Botany Vol. 118, no. 4 (2016): 621-635.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Portland Parks’ “Nature Patches”

Winter 2022 Nature is so beautiful when left to its own devices, yet crisply manicured lawns remain a status symbol. This is true in Portland,

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Responses