Organized chaos—Food, Roses and a Jungle Retreat

Contributor

Summer 2021

#LifeNotLawn

Approaching from any direction, this corner landscape blazes with color in high summer, and beckons you in winter with subtle silver foliage and tawny waving grasses. It’s unlike the yards on the other three corners and, most noticeably, there’s no lawn. As you approach, the staggered lines of a path pull your attention past a rusty planter to a dazzling mound of the reddest blooms of autumn sage you’ve ever seen. It’s a ravishment for your eyes: the colors, the patterns, the motions of purple blooms on pencil thin stalks swaying, hummingbirds diving, bees buzzing.

This is the Garden of Organized Chaos. Owners Sara and Grant chose to get rid of all the lawn in their yard, and instead now highlight a diverse mix of native and other well-adapted flowering plants. Woven together, the plants are a magnet for birds and insects, and create an island of habitat in a neighborhood of lawns.

The Fruit and Veggie Garden

If Sara honors your appreciative interest of the front gardens with an invitation to the back, you step down the staggered path and through a tall gate. She gestures dismissively to the triage center on the left (midget hydrangea with outsized blooms, persistent grocery store primrose, some pots of thin twigs and stalks). Looking up, you see clearly that the rest of the broad side yard provides all the tasty things a garden can offer. There are pears (Pyrus communis ‘Flemish Beauty’ and ‘Moonglow’), everbearing raspberries (Rubus idaeus ‘Heritage’), and metal raised beds with greens, squash, and towering sunflowers blurring the boundaries of path and bed.

The experience of raising a thing from a seed, nurturing it through its growth, then harvesting it for your table is a ritual you can easily adopt to connect to nature, to the cycle of life. Horticulture therapy describes the measurable benefits you get from gardening and the hands-on experience of growing your own food in a vegetable garden is transformative.

There was no lawn in the side yard here when I came on the scene. The side yard was already a version of its best self with some square raised beds and big pots spilling with flowers and vegetables. The problem was the chaos (rampant growth and ever-increasing pots of seedlings, divisions, and irresistible nursery acquisitions) didn’t have an ample layout to contain it all. There was nowhere to walk nor room to grow enough to match Sara’s energy for the task.

We organized the existing square raised beds in a fun staggered layout with enough room between them for the inevitable profusion. Now they’re easy to access and have a legibility that frames the chaos and welcomes engagement. We added long raised beds for berries and curved beds with black metal edging for the pear trees. We designed a sitting nook for Sarah to have a chance to put her feet up and enjoy the fruit of her labors, but I think her motor idles too high for sitting. Perhaps the character of a fruit and veggie garden is defined more by activity than by leisure. Place the veggie garden in a distinct part of your yard, so you can use the outdoors for activity and rest, each mood with its own room.

Instead of tending a lawn in your own side yard, you can grow food as Sara does. To be sure, this still is the Garden of Organized Chaos. In the half-circle beds anchored by pear trees, Sara added unusual salvias. Several prairie Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha) are potted up along the edge. This is a working room of the yard. Projects happen here. Messes are made and seeds sprouted. Tomatoes ripen and minds come to play and learn. Can your lawn offer as much?

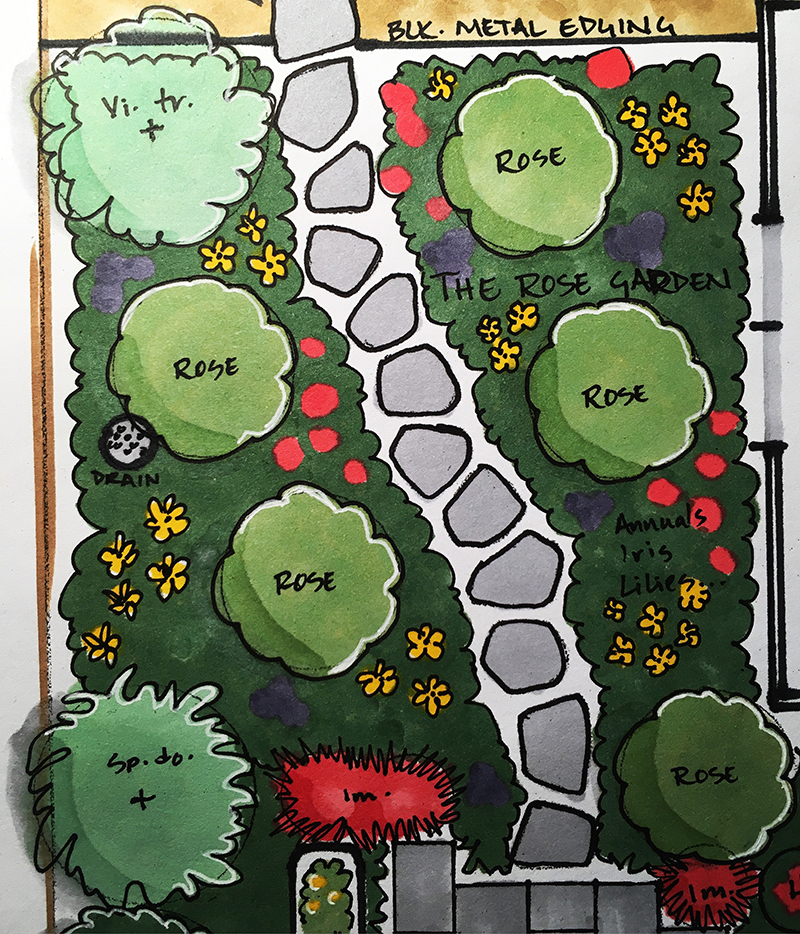

The Rose Garden

Have you ever sipped the morning dew from a rose in full bloom? It is the most exquisite—potentially erotic—experience you can have in your garden. Only indulge if you grow richly scented roses that you know have not been sprayed with anything gross that you would never knowingly put in your yard, let alone your mouth!

Why group roses together in a dedicated rose garden? Cultivated varieties of roses—be they hybrid teas or floribundas or some type of continuously blooming hybrid—thrive in rich, well-irrigated soil. You can either pamper your entire yard and spread these beauties everywhere, which is wasteful of resources and your maintenance time, or you dedicate the perfect pocket for their excellence to shine with all the fertilizer, compost, water and tending they need to thrive.

The Rose Garden here is one of those pockets, or rather a hallway, as it connects the Fruit and Veggie Garden to the broader Jungle Garden. This pass-through space is even lovelier for the close-up sensory experience of roses. ‘Julia Child’ rose (Rosa ‘Julia Child’), with its fragrant yellow bloom, is a particularly delightful variety you meet along the way.

With ample spacing between the rose bushes, Sara added monkey flower (Mimulus sp.), miniature conifers, zinnias, and gas plant (Dictamnus albus). The repetition of the rose bushes with a spine of bold-sized flagstones does the job of creating just enough order that experimental planting doesn’t overwhelm with randomness—it’s just the right amount to keep it interesting.

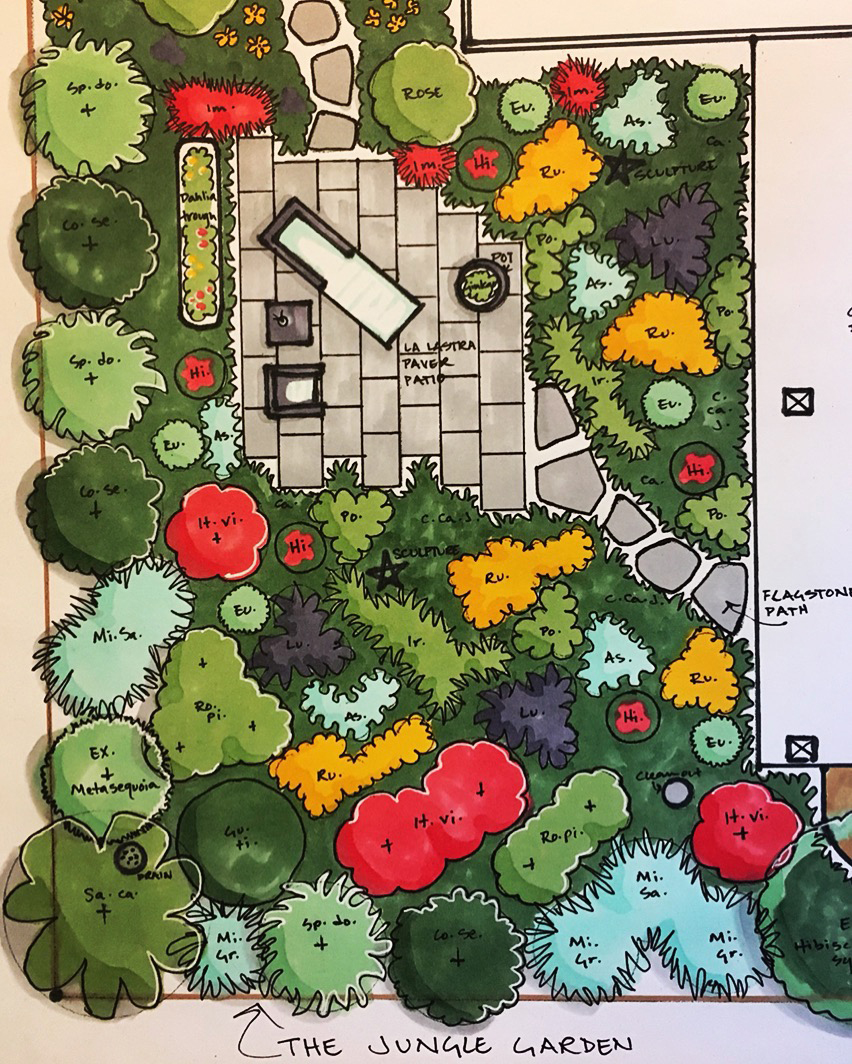

The Jungle Garden

Lawns are useful for play and entertaining but what is interesting about a lawn? Does it capture your attention and inspire awe? Sara’s back lawn was mottled, wet, and mushy underfoot—in other words, not awesome. It dominated the space with narrow borders of anaerobic, soggy ground, and yellow and misshapen plants; nothing happy was happening there, save for the tenacious dwarf dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides, unknown cultivar) in the corner. Sara nailed it with that choice. Its roots penetrate the wet soil, grasping so thoroughly that when I attempted to transplant it, I changed my mind out of respect for its foothold.

Someone had rigged up a little pipe and small pockets of river rock to divert standing water out of the yard but it wasn’t working. Builder’s solutions often involve a mess of pipes and gravel, a dearth of plants, and a problem down the way for wherever the excess water gets dumped. We approached the problem differently by first considering wet ground to be an opportunity, not a problem.

The standing water was along the back fence, not affecting the house or its foundation. That, coupled with the unloved lawn led us to my favorite solution for any wet yard: a patio for dry-footed outdoor living surrounded by a lush wetlands garden of plants that thrive in a heavy soil with plenty of water.

And you know what? There are a lot of great wetland plants. It really is an opportunity to grow some beautiful plants that would require excessive water input on a drier site. In Sara and Grant’s Jungle Garden we first established a hedge to buffer the “fenciness” (not at all related to fanciness). “Fenciness” occurs when your entire visual field includes too much fence. Redtwig dogwood (Cornus sericea) and western spiraea (Spiraea douglasii), both northwest natives fond of riverbanks and sloughs, alternate along the back fence. They’re joined by fellow natives: swamp rose (Rosa pisocarpa) and blue elderberry (Sambucus caerulea). I had high hopes for the elderberry and thought it would be the tallest of the hedge community. Instead, it’s limping along in obscurity low under the blue rush. Clay seems okay for this species, but apparently not in a marsh.

For diversity, extended bloom season, and fun, we mixed non-natives into the hedge. One of Grant’s few requests was for big grasses, as he craved a jungle retreat. Now variegated giant reed (Arundo donax ‘Peppermint Stick’) reigns and makes a dramatic, jungle-themed statement, with its broad green and white striped leaves. The giant reed is joined by two varieties of maiden grass (Miscanthus sinensis ‘Gracillimus’ and ‘Sarabande’). These big grasses layer well in the mixed hedge and blur the edges. A quick sidebar: luckily, variegated giant reed is not invasive in the wild here as it is in California, but that’s something to be aware of before planting Arundo donax. Check your local invasive plant list.

In the middle of the garden is a patio of modern rectangular pavers set with a staggered edge. Wetland perennials wrap the patio in seasonal waves of bloom that start off in spring with camas (Camassia quamash) and checker-mallow (Sidalcea virgata, syn. S. malviflora), then peak in late summer with Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum) and swamp hibiscus (Hibiscus moscheutos). A matrix of dense sedge (Carex densa) throughout the perennials, and blue rush (Juncus patens) with the shrubs, knits the ground layer together.

The chaos element in this garden is on me. I wanted to use the western native coneflower (Rudbeckia occidentalis) in the mix. The bold black cones, absent of ray petals, seemed to suit Sara’s quirky style. I’d seen plants in the wild, but never in a garden. As I designed the planting, I envisioned those natural plants I’d observed—they were a couple of feet tall in a wet meadow—and I scattered them through the middle and front of the planting. The first summer, they towered up to six feet tall. Sara cut them so they didn’t smother the path and discreetly wondered what I was thinking, planting such tall things where I had. Now I know, garden conditions suit western coneflower well, monstrously well!

Conclusion

Think about how easily things become familiar, such as face masks at the ready—cupping chins, dangling from ears, swathing necks in medical blue and patterned fabrics. What was once, not so long ago, weird and noteworthy has become “this is what we do now.”

What if we normalize a lawn-free yard? What if, one by one, we bend the ideal of beauty to look fundamentally different than the conventional lawn-with-foundation-shrubs standard? Each new version need not be identical. Like the variety of facemasks, the styles and colors, the prints and solids, your lawn-free front yard can look like your expression of beauty. And, significantly, it can function in a network with the beauty that your neighbors create to support greater insect and bird diversity, to support life. It’s not just one transformation, not just one anomaly in the subdivision that will make an impact; it’s the normalization of this new look, this new standard. It says, “We value wildlife and we’re having fun doing it.” It says, “I’m willing to put in the effort to make something different towards something better.” It says, “This is beauty.”

Postscript

Recently, Grant and Sara moved away from Eugene and from their Garden of Organized Chaos. Paul and Andrea, the lucky new owners, and I were looking at the heavy metal switchgrass (Panicum virgatum ‘Heavy Metal’) when Paul asks me candidly, “What’s the intent behind this space?” I paused and thought of Sara and Grant, of their love of art and flowers and bees, and of their disgust for lawn. Their legacy is a vibrant habitat that inspires the neighborhood. Then Paul asked, just to clarify, “It was intended to be a naturalistic look, not one where everything is pruned into little balls, right?” We laughed. It is a new approach, but legible and beautiful, because we know nature’s beauty when we see it.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Expand Your Palette: Waterwise Plants for your Landscape

There’s nothing more thrilling to plant lovers than discovering new plants to test in the garden. Here in the southernmost corner of California, we have

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Portland Parks’ “Nature Patches”

Winter 2022 Nature is so beautiful when left to its own devices, yet crisply manicured lawns remain a status symbol. This is true in Portland,

Responses