Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Sustainable Gardening

I’m a gardener, but when I went to college, I did not study horticulture—I majored in history, intending to become an academic. When I earned a master’s degree, I had lost interest in academia and decided that gardening would be a good way to earn a living. I landed a job as a gardener at U.C. Berkeley and eventually became a lead gardener.

Like most maintenance gardeners, I spent more time dealing with weeds than on any other task. Eventually I learned to enjoy weeding, a relaxing and meditative activity, and realized that weeds were a highly variable group of plants capable of spreading themselves by any number of ingenious strategies. Almost all weeds are able to germinate, grow, and reproduce quickly anywhere there is bare or disturbed ground, and they have special abilities to thrive in particular, often extreme, circumstances. What’s more, I learned that weeds have a history, parallel to and intertwined with human history. I thought I had left the humanities behind when I opted for a career in horticulture—I now believe that horticulture is one of the humanities.

Weedy Plants Are a Permanent Part of Urban Landscapes

Shortly after beginning my gardening career, I started as an adjunct instructor in the Department of Landscape Horticulture at Merritt College in Oakland, California. I spent most of my time as an instructor teaching Merritt’s weed course, then titled “Weed Identification and Control.” I eventually renamed my course “Weeds in the Urban Landscape,” a title that acknowledges that, whatever we decide to do about the weeds in our gardens, they are an integral part of our landscape. Weeds have been following us around since we began disturbing the ground through clearing and farming wild land, building structures and roads, grazing domestic animals, and planting vegetation that we regard as pleasing.

Weedy plants, which grew quickly and spread rapidly, first thrived in the bare ground exposed by retreating glaciers. Eventually they were followed by grasslands, shrublands, and forests—more stable plant communities in which there was little disturbed ground to colonize. As Edgar Anderson, a botanist and author of the eminently readable (and unfortunately out of print) book Plants, Man and Life, points out, they were plants that were adapted to grow in barren soil and now thrive in the disturbed soil created by human activities. They’re ours, we provide the right conditions for their success, and we’ll never eradicate them unless we manage to eradicate ourselves first.

Weediness of Plants Varies

I divide weeds into three categories: invasive, aggressive, and manageable. Some weedy species are so vigorous and their effects so damaging that they cannot be ignored. These plants are invasive and likely to move into native vegetation and take over. The second group is those that need to be controlled and contained but won’t immediately take over your entire garden. Then there’s the third group, weeds that are beautiful and not considered weeds at all—except for the inconvenient fact that they spread, so they need to be managed. These are the self-sowing garden flowers, both annuals and short-lived perennials like California poppies that can be managed by removing excessive quantities, pulling them from where they are not wanted, but leaving the rest. Despite weedy habits they are less aggressive, beautiful, mix seamlessly with chosen plants, and are welcome short-term guests in the garden. I would like to devote the rest of this essay to some of my favorites in this category.

Worthy Plants that Need Management

Of the garden weeds, scarlet pimpernel, Lysimachia arvensis, is my favorite. The Scarlet Pimpernel is the name of a character from a novel published in 1905 by Baroness Orczy. It is the pseudonym of a dashing English aristocrat, who rescues French nobles condemned to the guillotine during the French Revolution. He is known by the symbol on his ring, the scarlet pimpernel, a common annual in Europe. It is a common weed here too, often found in our own gardens.

Scarlet pimpernel is a sprawling annual that grows through the winter and blooms late in the spring, lasting well into summer in fairly moist locations. A member of the primrose family (Primulaceae), its oppositely-arranged, oval leaves are thick and shiny, along squarish stems. The flowers are small and brightly colored, and have been used as decorative motifs not only on aristocrats’ rings but on teacups and pottery. They produce adorable spherical seed capsules, whose upper third is a lid of sorts, which falls off and allows the seeds to spill out when ripe. On ground that is bare most of the year, there is little reason to remove this weed at all—it occupies space that could be occupied by uglier weeds. In plantings, it can provide an impromptu winter ground cover, or blend quite nicely with whatever else is growing there. One is tempted not to think of it as a weed at all, but it is wise not to let it set too much seed.

White cudweed, Pseudognaphalium luteoalbum, is an upright annual in the daisy family whose leaves and stems are covered with soft, silvery-gray hairs and whose blooms are bright yellow flower clusters surrounded by silvery gray bracts. It is the sort of plant gardeners often use to soften more intense colors in flower beds, and if it appears there, it can be left for this purpose, but it sets prodigious amounts of seed, and it is wise to remove it before this happens. I would not plant it in flower beds purposely. There are plenty of better-behaved gray plants available, many of them perennial.

A pleasant little weed that often occurs in lawns or at the edges of flower or shrub beds is field madder, Sherardia arvensis, a member of the coffee family (Rubiaceae). In some ways, field madder resembles a miniature bedstraw, its more aggressive—and less pleasant—cousin. Fine stems are covered by whorls of narrow leaves with pointed tips, a half inch long or less. Stems can grow up to a foot long but are usually considerably shorter. They radiate from a crown atop a slender taproot and form dense, tufted mats. The tiny pale blue to pink flowers grow in clusters at the tips of the stems from January to May. The plant provides a textural element in non-monoculture lawns, and may be left as a filler or edging in flower or shrub beds. In rural areas, it can be found in grasslands, meadows and orchards.

Miner’s lettuce, Claytonia perfoliata, is a winter annual native to California that is really difficult to regard as a weed, except that it does volunteer quite freely. It likes shade and moisture, and is often found growing in fruit orchards, where I suspect it is sometimes sown deliberately, as it provides a fairly benign alternative to weeds that would otherwise grow there. Its smooth, shiny, semi-succulent leaves are more or less circular, and completely surround the tip of the stalk. They are edible, with a mild flavor and crunch similar to lettuce. They are a perfect green for winter salads, and are grown commercially for this purpose in Europe. The small white flowers grow on a short stem that emerges from the center of the leaf. They can be included in salads, also. In cool summer areas, miner’s lettuce can persist well into summer, and a second crop is possible in irrigated ground.

Robert Flogaus-Faust CC BY 4.0

Another weed that provides tasty greens for winter salads is chickweed, Stellaria media, a low, spreading, tender annual that, like miner’s lettuce, likes shade and moisture. This plant has a habit much like scarlet pimpernel—long stems from a central crown with fibrous roots that lie flat on the ground, and opposite, oval leaves which are a half an inch long or less. These are light green, almost chartreuse, and can brighten shady areas. When it grows by itself, or interspersed with only a few other weeds, there is little reason to remove it—it makes an attractive temporary ground cover, and a good addition to salads. Flowers are tiny and white, with five deeply-cleft very fine petals that give the blossom the appearance of a star with ten points.

There are several wild plants in the genus Geranium, all European natives regarded primarily as weeds, that are quite common in urban landscapes. My favorite is the dovefoot geranium, Geranium molle, a shade-lover whose palmately-lobed leaves are covered with tiny, soft hairs, and whose small pink flowers are quite beautiful. It can be a pleasant addition to a mixed flower bed, or provide a temporary ground cover among shrubs. Once it begins setting seed, it becomes rangy and far less attractive. This is a good time to start removing it, as you won’t want it to drop too much seed. The same is true of G. dissectum, the birdsfoot, or cutleaf, geranium, with deeply and finely-lobed leaves, smooth and bright green, which forms a larger and more sprawling plant than G. molle. It does well in full sun, and can invade lawns, where most people don’t welcome it. In other places, it can be fairly attractive, for a while, due to its lovely small magenta flowers.

Perhaps the most attractive of all the wild geraniums is a perennial, Geranium robertianum, the “herb Robert” of English gardens. This plant has dark green leaves, often tinged with purple, especially on the petioles, and mottled magenta flowers. It is sometimes planted as a shade-loving ground cover or appears on its own and is welcomed, but it needs to be kept under strict control, as it often overwhelms gardens, spreading both by seed and underground stems. It has become a serious problem in wild areas, where it can form solid ground cover beneath trees. I would not tolerate it at all in gardens adjacent to native woodlands.

There are a number of annuals and short-lived perennials that gardeners can plant that self-sow freely, often travel some distance, and then become regarded as weeds. With careful management, however, these can be very rewarding plants. Probably the best known, and most cursed, is the forget-me-not, Myosotis latifolia, whose abundant fruits adhere easily to clothing and animal fur, helping them spread everywhere. Hiking trails in woodlands near urban centers are often lined with them, but they do not venture far from the trail. They love shade, but will quickly occupy almost any space in a garden that something else does not occupy first. They bloom most heavily in the spring, but can produce successive generations throughout the summer in well-watered gardens (as can many winter annual weeds; this is another good argument for growing gardens that need minimal water in the summer). Good management includes pulling them out of the ground as soon as they begin setting fruit, even if they are still blooming—they will replace themselves very quickly.

Close behind the forget-me-nots in rambunctiousness is sweet alyssum, Lobularia maritima, a mustard family sun-lover from the Mediterranean that is among the most drought-tolerant of all annuals. It even thrives in unirrigated ground in hot interior areas of central and southern California if it gets a good start in the spring. Drifts of this plant in uncultivated ground can be preferable to stands of dried-out grasses, thistles, and other weeds, or to the stubble they leave after mowing. Sweet alyssum continuously produces heads of tiny four-petalled flowers, usually in white. There are pink and purple seed strains available, but repeated self-sowing generally turns them white after a few generations.

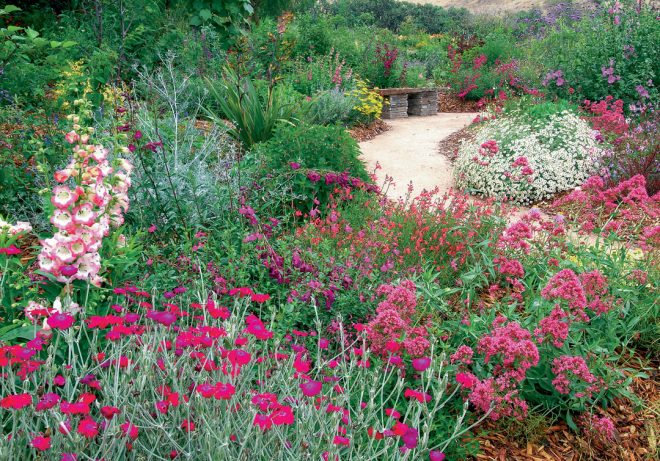

Red valerian, or Jupiter’s beard, Centranthus ruber, is a Mediterranean perennial that likes to grow among rocks or in cracks or gaps in concrete—truly a “wall plant,” as many of the old English garden books would have it. It probably originated as a garden escape, and is still valued in many gardens. It can be easily recognized by its dense terminal clusters of narrow, long-tubed flowers, about an inch long and less than one eighth inch wide. Most of the time the flowers are a characteristic dull magenta color, but they can vary from white to dark red. These sit atop compact, bushy plants one to three feet tall with shiny, bluish, ovate leaves set opposite one another. The base of the plant tends to form a woody crown, from which new branches will form if old growth is cut back. Jupiter’s beard blooms most heavily in spring, but will re-bloom throughout the warm season if pruned back. Repeated pruning causes the plants to become awkwardly formed and excessively woody after a few years; when this happens, just rip them out and allow them to be replaced by their abundant seedlings.

Along with the spreading acceptance of more relaxed garden styles and the need to reduce pesticide use, there has recently been a growing understanding that cultural practices play an important role in managing a garden. This allows for some blurring between the categories of weedy vs. desirable plants, a boon to gardeners like me who think that the more diversity in a garden, the better. Granted, it’s important to guide plant reproduction to produce desired results, to create the garden we envision; but there is a great deal of joy to be gained from standing back and watching what happens when we don’t intervene. Plants will compete with one another and possibly surprise you by some crowding out and even “controlling” others. Some “weedy” plants are beautiful and mix well with the other plants we choose; if we allow them to find their place in our gardens they can add an element of unpredictability and spontaneity that complements our efforts to plan, design and structure our gardens. If we learn how to identify them and what they are capable of, we can have it both ways: we can allow for chance and spontaneity, but still plan our interventions to ensure our gardens do not stray too far from our visions.

Richard Orlando is the author of Weeds in the Urban Landscape: where they come from, why they’re here and how to live with them, published by North Atlantic Books, Berkeley California, 2018.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Portland Parks’ “Nature Patches”

Winter 2022 Nature is so beautiful when left to its own devices, yet crisply manicured lawns remain a status symbol. This is true in Portland,

Readily Available Low-Water Plants for a Warming Climate

Fall 2022 Al Shay is the manager of the Oak Creek Center for Urban Horticulture on the campus of Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis.

Responses