Contributor

- Topics: Archive

In the previous installment (July ’07), the author focused on shaping spaces and manipulating their surrounding plant masses. He now turns to possibilities for manipulating spatial perceptions that are inherent in the physical and visual characteristics of plants. Fundamental to this discussion is the goal of retaining attention within the space itself by making the plant surfaces interesting. This is not difficult to do, as plants are intrinsically interesting, but it is how plant characteristics can be used to influence perceptions, and how this influences the space manipulations that were discussed previously, that may reinforce or negate space formation decisions.

In considering how plant characteristics can affect the apparent size of garden spaces, we need to accept two assumptions. First is the notion that visual complexity contributes to interest; in other words, a space with a complex form made of plants possessing a variety of characteristics will interest us and hold our attention longer than a clearly articulated space with second notion is that spaces that hold our attention longer are likely to be perceived as larger than those that we comprehend at a mere glance, and that provide no further reward for our prolonged attention. Many gardens seem to be planted on the principle that more variety will always be better. At some point, however, complexity and richness become excessive; and the resulting clutter and confusion make spaces appear crowded and cramped rather than expansive. The result can be even more overwhelming when complexity and richness are expressed in obtrusive and insistent patterns.

Rather than applying complexity randomly in design, its use to make spaces seem rich and interesting (and thus larger) must be balanced against a simplicity that provides spatial coherence. If we think of complexity as a characteristic that attracts attention, then considerations of which parts of our gardens to make simple and which to make visually complex become vital to the process of making spaces seem larger. Balancing and locating complexity and simplicity should reinforce, rather than conflict with, the space-shaping considerations described in the previous article. Thus we need to think of contrasting richness, variety, and complexity with the simplicity and uniformity of surfaces.

Simplicity, Complexity, and Contrast

We use the word “accent” to describe an object or feature that attracts our attention in a scene. Objects so used are effective tools for directing ones attention within a space. The greater the contrast between accents and their their surroundings, the more effective they are at drawing our attention. Sharply defined contrasts are more effective than gradual transitions. (Retaining interest in an accent is a different consideration and is more a function of the accent’s material composition and intrinsic or symbolic meaning.) If accents are placed at the end of a long axis, they tend to emphasize its visual dominance and thus may reinforce the way it makes the space seem larger. If placed on a cross axis, accents may attract attention in ways that diminish the effectiveness of spatial shaping.

Where space is small, the number of accent points should be limited and might possibly be centrally located or placed at the end of a main axis. Larger spaces may accommodate several accent points located in ways that encourage the eye to wander, or dance, around and within the space. These ideas lead naturally to a consideration of the potential for patterns in the landscape to make spaces seem larger. Pattern, however, is a topic deserving of its own article. Suffice it to say that patterns can be compelling, but, if used without restraint, may overwhelm our perceptions and, therefore, are best used with care. Perceptual “tricks” using pattern may backfire and should generally be avoided.

Architectural features, such as gazebos or sculptures, are common garden accents. But plants may also act as accents when their forms, sizes, colors, and/or textures contrast with their surroundings. While architectural and sculptural features may contrast more sharply with a plant backdrop, plant accents may compensate for this by providing seasonal changes—in color, texture, or form—that may make a space observed over a long period of time become more interesting and engaging. In addition, plant accents may appear at different locations in the garden at different seasons or even at different times of day.

The most effective accents are those that contrast boldly against a simple, unified background that retreats from attention. These contrasts may be accomplished through the manipulation of form, color, texture, and light conditions. We shall consider these factors next.

Plant Characteristics That Affect Space Perception

The density of plants, their colors and textures, and the resulting light effects may strongly influence space perception, and these characteristics can be used to reinforce and augment the other spatial manipulations. Color, texture, and light are complex phenomena; here, we confine ourselves to general rules for how they may be used to alter space perception.

Under typical daylight conditions, the colors of landscape features appear paler and bluer—more “washed out”—with distance. Thus plants with light-colored, glaucous, or blue gray foliage are likely to make a space seem larger than the same space surrounded by plants with dark foliage of a saturated color. The common saying that warm colors “advance” and cool colors “recede” expresses part of this effect, but it is also generally true that more intensely saturated colors advance, while pastel colors recede. Thus, plants with lighter colors and colors at the blue end of the spectrum may make spaces seem as large as possible. Lighter colors reflect more light, so this effect may be more pronounced under bright sunlight than on duller days.

An alternative approach for using color to alter space perception is to use plants with bright, saturated colors as strong accents within a space.

Light and Color

The shapes of spaces contained by plants vary with plant growth and maintenance but are relatively stable in comparison with the fickleness of plant colors and textures, which tend to change with the seasons. Color and texture perception is even more fickle as it responds to the most changeable of all factors that we shall consider: the light conditions under which we experience our gardens. Although our minds are biased to perceive that the colors of objects remain constant, the truth is that, under the changing intensity, color, and direction of light, the appearance of plants may change dramatically. Depending upon weather conditions, these changes may occur many times during a single day—even with the passing moment.

The combined impacts of light, color, and texture affect our perception of space, but their changeability and impermanence suggest that we not rely solely on them for creating or influencing those perceptions. All design rules about color, texture, and light need to keep in mind that the sun is a moving target and, so too, are the shadows that it casts.

Texture

The perception of surface’s texture is influenced by the size, shape, and arrangement of elements that compose the surface, and its distance from the observer. In the case of planting design, these elements are usually foliage but may include twigs or flowers. Perception is influenced by the way in which the leaves are held on the plant, and the degree to which they create depth and shadows. The effect of increasing distance is to make surfaces appear progressively finer and smoother. As a result, we are biased to perceive coarse textures as being closer to us than fine textures. A space surrounded by coarse textured plants is likely to seem smaller than the same space surrounded by fine textured plants. The influence of texture on space perception can be enhanced by using coarse-textured plants close to the viewer and finer-textured plants in the distance.

Light and shadow contrasts may dramatically enhance textural effects, thereby influencing space perception. We describe the light on overcast days as “flat,” because light and shadow contrasts are minimized. On those dull days, depth perception is reduced and spaces may seem smaller than when seen under bright, sunny conditions that create greater contrasts. Daylight and sunlight cannot, of course, be controlled, but we can consider how plants reflect, absorb, or transmit light, thereby creating shadow patterns within themselves or on the ground plane. The differences in perception created by flat or directional light are more pronounced on loose, open plants than on the smoother surfaces of plants with tightly overlapping leaves. Thus, the former tend to look much coarser under bright directional light than they do under dull, non-directional light.

We respond to light and shade differently under different climatic or seasonal conditions, and our moods are likely to affect our perceptions of space. For example, a pool of shade created by a tree canopy might appear dark and forbidding under cold winter conditions but most welcome in a bright summer landscape. Consequently, we may imagine a space whose boundaries are lost in shadows as larger than it actually is in summer and smaller in winter.

Camouflage

Together, color, texture, light, and shadow can conceal the locations of spatial boundaries by camouflage and thus obscure and confuse our perception of the extent of a space. These effects may occur in open tree canopies and may be translated onto the ground plane by the light and shadow patterns they produce. The brighter and more contrasting the sun and shadows are, the more pronounced these effects will be; because they are to a large extent dependent on light conditions, they are not fully controllable. While not necessarily making space seem larger, camouflage offers opportunities to affect space perception in ways similar to those of open shrubs that veil the perimeters of a space (see July ’07, page 50).

Some Final Thoughts

As these articles suggest, there are many design techniques that can be used to make garden spaces seem larger. However, making garden spaces seem larger is not necessarily the same as creating a successful garden design. There is, or should be, more to gardens than manipulations that enhance their perceived size. Nevertheless, considering how garden elements— space, plant forms, accents, ground planes—along with plant characteristics and light conditions can be manipulated to affect space perception is a useful discipline for thinking creatively about the design of one’s garden.

Design rules are never firm and immutable. One could imagine, for example, a garden packed full of plants flagrantly breaking every rule described above. Indeed, such a possibility may sound eerily familiar to many readers. While gazing into such a jungle, its owner may be mentally transported by the diversity of species and the resulting cacophony of experiences. To an objective observer, such a garden might appear cramped and crowded rather than spacious, but, in the eye and imagination of its owner, its fascination and charm expands endlessly. For a designer to condemn such an approach to gardening is shortsighted and narrow- minded. As long as the plants have sufficient room to grow and prosper and the owner can manage to squeeze among them, the garden is successful.

A final caveat: similar techniques for manipulating space perception are employed by painters and stage designers in more controlled and contrived contexts than occur in living landscapes. Visitors to art galleries and theaters willingly suspend judgment about reality and space perception; in other words, they knowingly collude in evoking the desired experience. These are not attitudes that we commonly bring to the experience of living in and using garden spaces. Techniques that may be acceptable in art and theater may be inappropriate in garden design. For example, contrivances, such as false or forced perspectives and scale changes that consist of reducing the size of objects to make them seem more distant, are likely to backfire when users become aware of these manipulations—as they are likely to do because of their more intimate involvement in the garden.

Unlike theaters and art galleries, gardens and landscapes are frequented and experienced under varying weather conditions and in moods that may range from those encountered in harrowing Monday morning commutes or languid summer evening strolls. More often than not, garden design techniques that depend upon users “suspending belief” will fail. It’s best to avoid blatant perceptual “tricks” or “sleights of hand” when designing landscape spaces. Check to see if the responses to all of the techniques described in these articles actually occur and are desirable in your garden. Don’t rely on them to ensure a design’s integrity. Above all, don’t be too clever. A surfeit of cleverness in landscape and architectural design is a recipe for disaster.

This survey of techniques to make garden spaces seem larger remains incomplete. I have omitted discussion of the effects of maintenance and of edge definition on space perception; I have only, in passing, alluded to architectural effects and built features; I have played fast and loose with the psychology of human perception; and I have avoided the entire subject of spatial design considerations from a moving viewpoint. However, I hope that I have dispelled some of the mysteries that surround planting design and made it clear that these spatial effects are not magic tricks, but may be practiced and explored by gardeners willing to lose themselves in reflection and observation of their own spatial responses. It should be fun, but don’t get lost in space.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

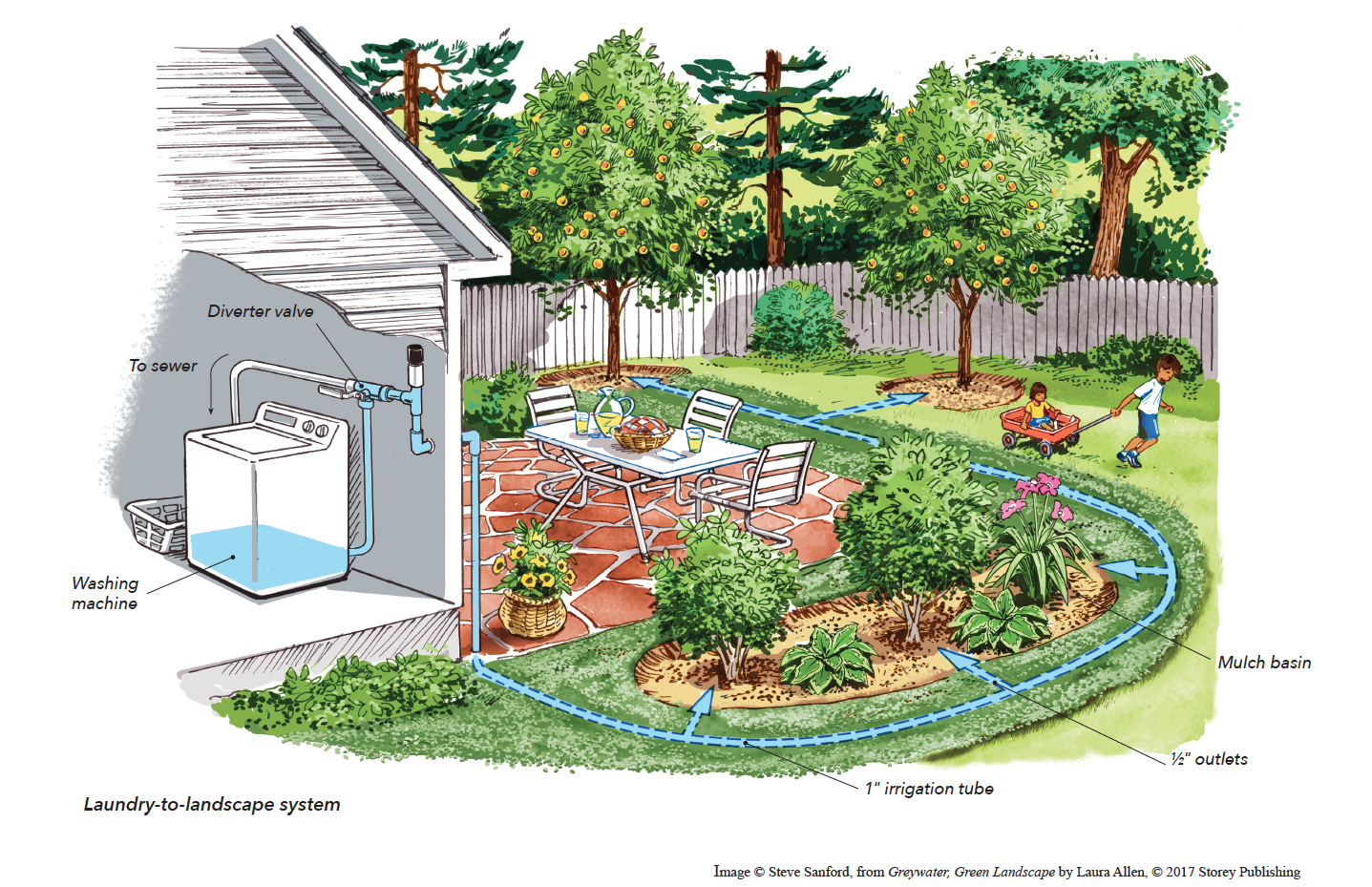

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses