Contributor

- Topics: Archive

A broad bed planted with shrubs, perennials and a twining vine, edges the small orchard in the Sonoma State University (SSU) Garden Classroom. A tree, underplanted with native grasses, bulbs, and flowering annuals, anchors the corner of the undulating border. Butterflies float about the shrubs and, near one end, a hummingbird enjoys a late breakfast. A covey of quail scurries under the tangle of berries edging the nearby creek. This vision was the inspiration for a dedicated group of volunteers.

Along the western edge of the parking lot, near the food production garden, a long-abandoned, bare, and hard-baked earthen berm is being transformed on a misty winter day. Students, staff and faculty gathered, undeterred by the drizzle, to plant and mulch a 150-foot-long hedgerow to provide wildlife habitat and please the eye as well. Because an abundance of quail frequents the Sonoma State University garden, many plants were specifically chosen to provide food and cover for these cheery little birds.

A hedgerow is a more or less linear row of trees and shrubs, often interplanted with annuals, perennials, and grasses. Look no further than the shrub border along the typical suburban backyard fence to spot what is essentially a hedgerow. A simple definition of “hedgerow” is a shrub border with benefits. Historically, hedgerows were planted in agricultural landscapes, and served multiple functions: providing firewood, berries, and other fruits; basketry materials; protection from wind and erosion; barriers to keep livestock penned in (and exclude predators); and habitat for small game. Hedgerows were often planted on top of an earthen berm to increase their usefulness as barriers.

Most commonly associated with the European countryside, hedgerows may also be found in Canada, Argentina, Australia, the Philippines, Mexico, and the United States. In Europe, where ancient hedgerows were razed during World War II and others lost to development, there is a growing recognition of their value in the landscape, and hedgerows are now being replanted and restored.

Laying hedgerows is a technique for managing single-species hedgerows to provide an impervious barrier. Tall growth, cut partway through and “laid over” horizontally, produces vertical shoots; the procedure is repeated over time, creating an increasingly dense living wall. Today, borders containing an informal mix of shrubs, perennials, and grasses are a more common solution rather than the labor-intensive, laid-over hedgerow.

In addition to being physical barriers, contemporary hedgerows provide habitat for birds and other wildlife and attract beneficial insects, pollinators, and insects that prey on pests. With a bit of cooperation, hedgerows can connect wild landscapes, providing important corridors along which wildlife can move through neighborhoods. With a slight zig and a zag, birds, insects, and other wildlife can move along the plantings into the heart of the campus. The hedgerows—there are now two at SSU’s Garden Classroom—connect to Copeland Creek. From its headwaters at nearby Fairfield Osborn Preserve, the creek provides an essential riparian corridor through the campus and the nearby community of Rohnert Park before it empties into the Laguna de Santa Rosa, a critical wetland habitat. A short way along the creek-side path, the long-established Butterfly Garden and Ken Stocking Native Plant Garden provide additional connections for wildlife that frequent the campus, which butts against nearby Sonoma Mountain.

Hedgerows may range in size from grand designs that include trees, to smaller scale plantings suitable for a typical residential fence line, or even sidewalk edges. For a border closely packed with plants or confined to a narrow space such as the edge of a driveway, look for plants tolerant of crowding and pruning, and resistant to disease. If the aim is a loose assemblage with room for plants to grow to their full size, choices are less limited.

The hedgerows at SSU are composed entirely of plants native to the region, but many hedgerows are a mixture of native and exotic plants. Hedgerows designed for wildlife habitat should be planted with at least 50 percent native plants. Native shrubs that are attractive to both wildlife and gardeners include toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), California lilac (Ceanothus), manzanita (Arctostaphylos), snowberry (Symphoricarpos), and coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica). A beautiful but little-known shrub, the silk tassel (Garrya elliptica), is a striking addition to a hedgerow, especially in winter when long catkins dangle from the branches. Twinberry (Lonicera involucrata) is a shrubby native honeysuckle beloved by hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees. The often unfairly maligned coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) provides important resources for wildlife includingwinter nectar and pollen for beneficial insects. Several compact, named varieties of coyote brush may be found at native plant nurseries. Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), an erect, shrubby berry that is much loved by quail, forms small thickets after only a few seasons.

To weave together the larger elements in a hedgerow, include perennials and grasses at edges or tucked between newly planted shrubs. Annual wildflowers are decorative, provide habitat, and will quickly alleviate the raw look of a new planting. Yarrows (Achillea millefolium) are an ideal addition, both for their ferny, fresh green foliage and the flowers that provide a valuable resource for beneficial insects. Many beard-tongues (Penstemon) are sturdy, spreading perennials that attract an abundance of hummingbirds and bees. Both yarrow and beard-tongue are available in a variety of flower colors, especially if the gardener doesn’t mind the occasional non-native hedgerow plant. Penstemon can be found in an accommodating range of sizes, from small-flowered groundcovers, to small shrubs with elegant, long-stemmed wands of flowers. Several native lupines (Lupinus spp.) provide valuable forage for quail, which first seek out the lush foliage, then later, the nutritious seeds.

If attracting beneficial insects is high on the priority list, no hedgerow is complete without buckwheat. California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum) may be without peer in attracting great numbers of beneficial insects, pollinators, and predators of numerous pests. San Miguel Island buckwheat (Eriogonum grande rubescens) is a spectacular addition to hedgerows, or experiment with some of the other wonderful buckwheats found at local native plant nurseries. Native asters are also a sure bet for attracting beneficial insects, and can provide nectar and pollen for many months, extending far into the fall.

When planning a hedgerow to attract wildlife by providing forage and shelter, be sure to consider and plant for resources throughout the year. When choosing plants for butterflies, remember to include host plants for caterpillars. Plants to support both honey bees and native bees are easily included in a hedgerow. Large hedgerows with naturally damp soil can support one of the native willows (Salix), whose catkins provide a valuable early spring resource for beneficial insects at a time when little else is in bloom; quail also relish the catkins, as well as the galls that grow so profusely on willows.

Invite the beautiful cedar waxwing to the garden with Pacific wax myrtle (Myrica californica). The vigorous fuchsia-flowered gooseberry (Ribes speciosum) provides wonderfully thorny nesting cover for a variety of birds as well as early nectar for hummingbirds. Thickets of native roses and berries provide protection from predators for ground-nesting quail and other birds. Quail also appreciate a bit of bare earth in which to take dust baths, easily provided for in most gardens.

Once your hedgerow is established, all that is needed is a bench, tucked into a discreet corner, from which to enjoy watching the wildlife in your own backyard.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

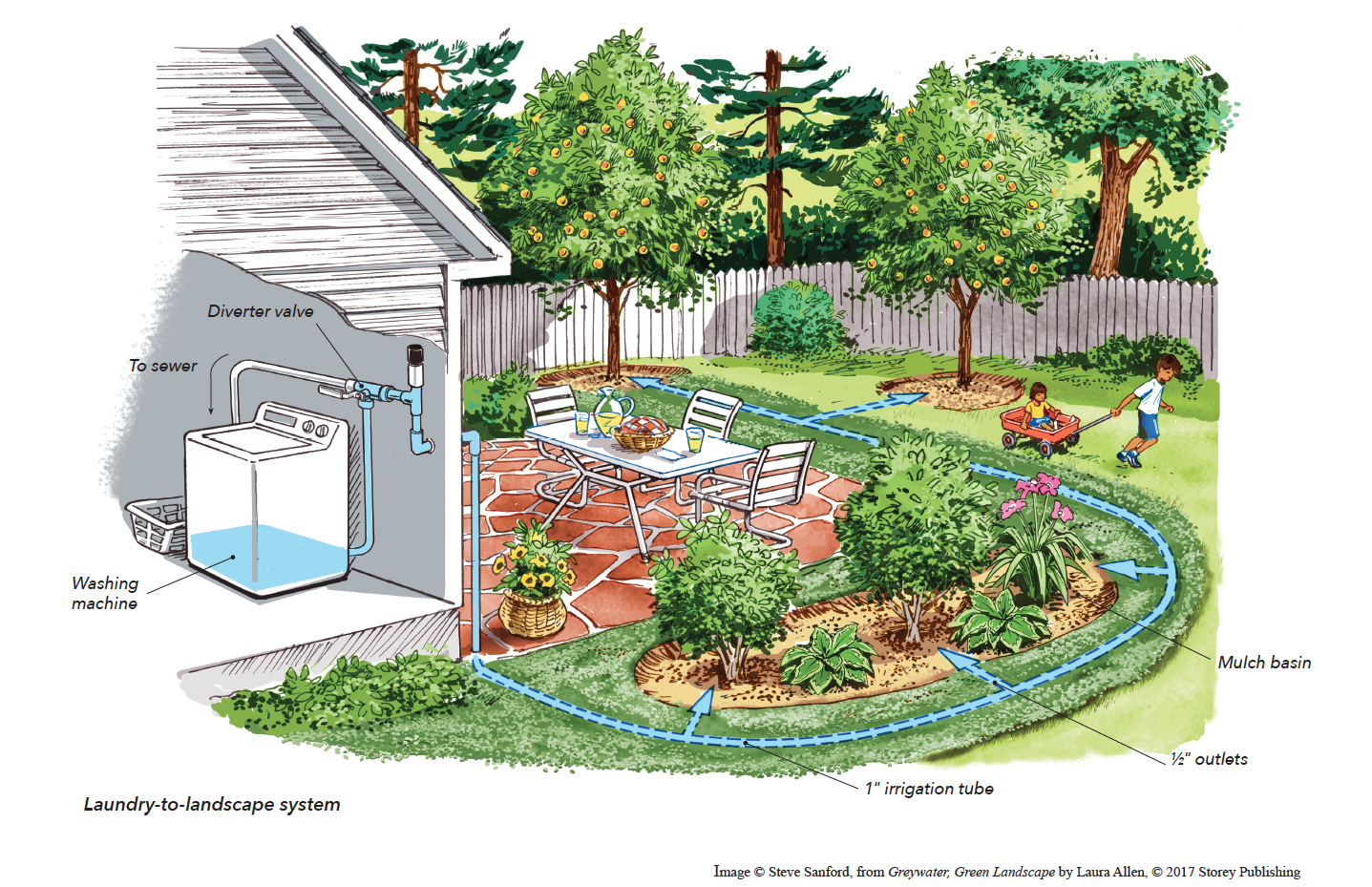

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses