Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens & Design

Each July, Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood celebrates its bucolic past with a garden tour that can best be described as eclectic.

Visiting Georgetown today, you get the sense of a restless place, jets coming in low overhead and laden big rigs barreling up and down freeway off-ramps, which penetrate the heart of the neighborhood. The cluck of chickens may not drown out the constant hoot of train whistles, but on entering the many gardens of this neighborhood you get a deeper and more permanent sense of the place and its history.

Laura Cassidy, a writer for the Seattle Weekly, says of Georgetown, “Just walking through the streets you witness post-squat, industrial bohemian chic.” This is certainly true. But the gardens of the neighborhood harken to an even earlier pre-industrial time, when the Duwamish River looped through the valley, when cows grazed and farmers harvested an abundance of foods from the rich soil.

Seattle isn’t known as a river city like Paris, London, or even St. Louis. It decidedly faces Puget Sound, the Pacific, and the world. Yet the first European settlers didn’t homestead on the shores of the city’s Elliott Bay, but paddled upriver to make their homes on the rich meadows along the Duwamish River.

The Duwamish, which is Seattle’s only river, along with its main tributary, Green River, runs 93 miles from its headwaters in the Cascade Mountains to the bay on which the city eventually developed. Before industrialization, the tidal river lazed slowly through the lush and soggy meadows of an estuary.

Though the river valley had been visited as early as 1840 by European explorers, Luther Collins was the first to stake a claim and begin farming there in the early 1850s. Others followed, and by 1900 the European households numbered around 385. Many of those households were recent immigrants from Italy who became market farmers for the burgeoning nearby Seattle. These farmers and the market they set up became the roots of Seattle’s now-famous Pike Place Market.

The original town, named Duwamish after the river, became Georgetown in 1890. Fourteen years later, it incorporated and was lauded as one of the most prosperous municipalities in the Northwest. Alongside the dairies and market farms, breweries and furniture makers set up their businesses. On the banks of the river, a steam plant for producing electricity and a trolley barn were built. A railroad yard for moving the many products of the new Northwest economy out into the world was built. Georgetown had the lively air of a boomtown, attracting tourists from nearby Seattle who took trolleys and riverboats to the many dance halls and saloons, especially on the weekends.

An independent city for only six short years, Georgetown was annexed by the growth-hungry Seattle in 1910. That same year, the first airplane flights in the area took off from and landed on the flats along the Duwamish. The once-loopy river and the bucolic meadows, which attracted the first homesteaders, became unrecognizable. The river was dredged and straightened in 1917, the meadows platted, and more houses and more businesses were built. By 1928, an airport was constructed on the alluvial soils, which grew to the current 594-acre King County International Airport, known locally as Boeing Field. It was this airport that inadvertently spawned a garden tour.

Georgetown was zoned industrial and residential in the 1920s and it remained largely a mixed community of residences, small business, and farms, but slowly the neighborhood became more and more industrial as Seattle grew. The last farm closed in the 1950s to make room for airport expansion. As urban residents fled the city for the new suburbs, like elsewhere in the United States, blocks of this formerly vibrant community fell to industrial developers. Viewed as poisoned by industry and uninhabitable, the residential core of Georgetown was reduced to a fraction of its former self and the old wooden homes and their gardens became tilt-up warehouses, factories, and showrooms. This development continued at a vigorous pace until the 1980s, then slowed. Several of the original old homes and some small businesses that served the locals remained among the constant drone of industry.

Then, in 1988, a lifelong resident of the neighborhood, Jon B. Dove, bought one of the boarded-up historic homes of the area. After taking possession, one of the first things he did was clear the garden. Pulling back blackberry brambles, which covered the property and the house, and removing years of trash, Dove discovered remnants of the former garden, notably a mop-headed hydrangea from the 1940s and a birch and mountain ash probably from the same time.

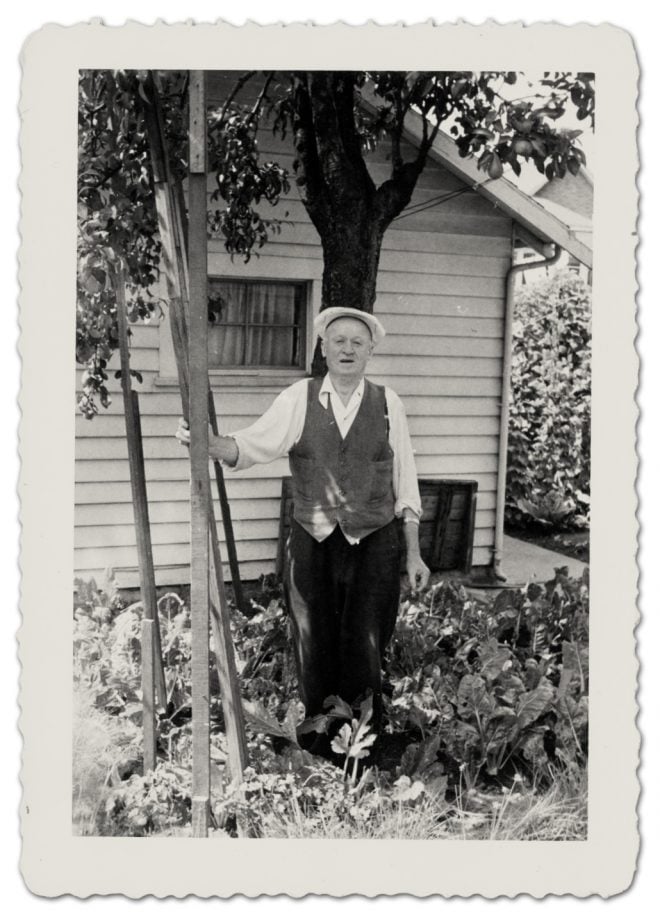

Jon was a working gardener in Georgetown since he was a teen and he began his new garden by creating beds with grass clippings and cast-off plants from his client’s yards. Everything grew quickly in the rich soil. Dove was greatly influenced by the neighborhood gardens he admired and worked in as a youth. Likewise, his garden became an inspiration for others and strengthened an already active gardening community in the flight pattern of Boeing Field.

By the mid-90s, Boeing Field was looking to expand again, allowing major air cargo flights in and out of this urban airport. Tolerant of the airport’s noise and pollution for decades, the residents of Georgetown were fed up. “This was going to kill the neighborhood,” says Dove. The city needed to see that people were still tending the fertile soil and living in this forgotten neighborhood. Members of the Georgetown gardening community were already batting around the idea of a garden tour.

Dove decided to take action.

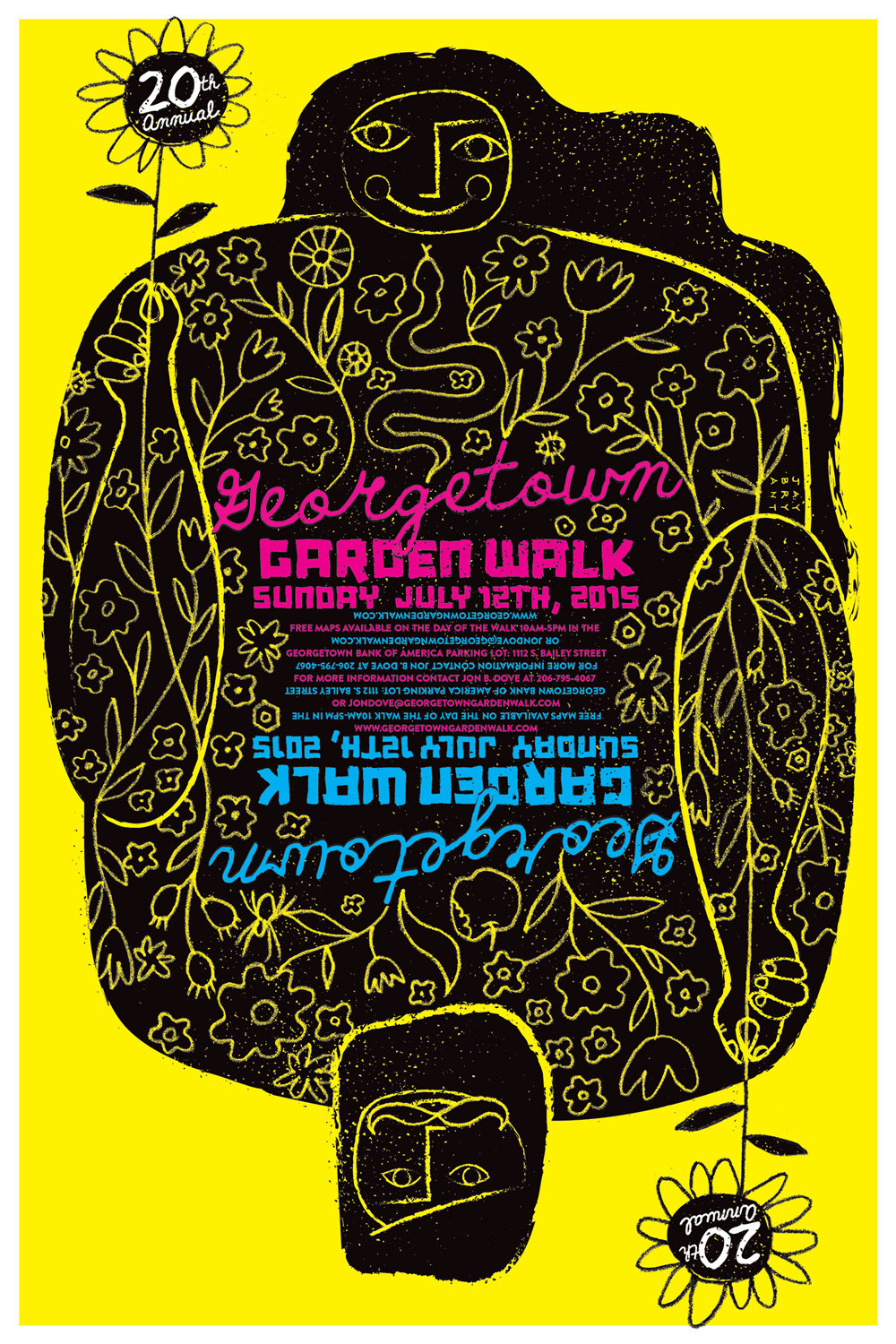

In August of 1996, the first Georgetown Garden Walk, touted as the only free and walkable garden tour in greater Seattle, took place. Fifty people toured thirty open gardens; it was the first community event in Georgetown since 1950s. The next year an ad in the Seattle Times announced the tour. Attendance doubled.

Then, in 2000, the Seattle Times in conjunction with the Northwest Flower and Garden Show, and the Washington Park Arboretum, awarded Dove the grand prize in the Pacific Northwest Gardens contest. They hailed his garden as “A Miracle in Georgetown.” That year, the garden tour attendance exploded.

Dove’s garden, a mix of formal and naturalistic styles, which he considers Edwardian, was praised by the judges as “a stellar effort” and “an outstanding example of creativity and spirit.” “In a larger sense, ” wrote Seattle Times journalist Dean Stahl, “he also won recognition for his quiet efforts toward creating beauty in a neighborhood not particularly known for it recently.”

Since the garden tour’s inception, it is hard to deny that Georgetown is once again a boomtown. No longer ignored, it is one of the hippest neighborhoods in Seattle. The trolleys are gone but visitors stream into the neighborhood weekly to enjoy the many restaurants, galleries, and bars. Today, Georgetown is home to the Seattle Wholesale Growers Market, a co-op for regional flower farmers dealing in locally grown flowers, a small water garden nursery, and many antique stores featuring garden-related items.

On July 12, 2015, the Georgetown Garden Walk celebrated its 20th anniversary. Attendance was well over 1,000. From the beginning, Dove insisted that the garden tour be free to the public. Anyone in the community is welcome to share their garden with the public—it is not a curated tour. Georgetown Garden Walk is the only residential event in a neighborhood now chock-full of arts and music events throughout the year. Of the 30 gardens on last year’s tour, Dove’s remains the only one open each year since the first tour in 1996.

In 2011, Cross Pollinate, a sister organization to the garden tour, began promoting local artists by having gardeners host plein air painters or the work of local sculptors in gardens and multimedia installations in the neighborhood’s green spaces and traffic circles during the tour.

Georgetown historian June Peterson praised Georgetown’s early backyard gardens for their “rabbits and chickens, which helped to supplement the Sunday meals of many families.” Those gardens are back. Vegetable patches, chicken coops, and beehives are common now. You can also see gardens lush with ornamentals much in the fashion of Dove’s “Edwardian” garden, or devoted to native plants. And as some of the older homes are razed to build clutches of minimalist condos and townhouses, the new trend is for more stripped-down gardens. Yet some of the more traditional gardening styles that inspired Dove in his childhood are still in evidence, too.

Residents describe their gardens variously on the tour’s handout calling them “A feast for the senses,” “A jungle within a city lot,” or simply “Peas and harmony.” In a sense, Dove and the gardening community of his childhood neighborhood have put Georgetown back on the map.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Responses