Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens & Design

It was meant to be a quiet weekend for two on the spectacular Mendocino County coast of Northern California, but by Monday we found ourselves the proud, if somewhat stunned, owners of a second home. Buying a house was not our intention. But the compelling property that has become Frog Song Farm was perfect for the life we anticipated in retirement. We envisioned a family retreat for our four children, their future spouses, and a place of enchantment for our then-only-imaginary, grandchildren. It was October, 1998.

But the vision we saw that weekend meant something different to each of us. My husband loved the little town of Point Arena with its world-class surfing, dramatic cliffs along the ocean, and historic lighthouse. He saw the possibilities in the multiple houses on our property. As a life-long gardener, I loved the fact that the original owner had laid out the roads and lawns, planted 200 redwood seedlings, built a half-acre pond, and cleared the pine forest above the pond. There, beckoning to me, was almost three full acres of bare hillside begging to become a garden. Designing and planting that garden, with generous help from my daughter Di, has been the most creative endeavor of my life.

Point Arena is approximately 100 miles north of San Francisco at the southern end of Mendocino County, a few miles from the famed Sea Ranch development. Our 30-acre property sits two miles inland at an elevation of 850 feet with a view of the Pacific Ocean—just above the daytime summer fog on most days.

Our property contains two distinct ecosystems. The closed cone pine forest consists of bishop pine (Pinus muricata), Coast rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum), coffeeberry (Frangula californica), Pacific wax myrtle (Morella californica), and manzanita (Arctostaphylos columbiana, A. nummularia). The mixed conifer forest features Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), grand fir (Abies grandis), Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and redwood sorrel (Oxalis oregana). Rhododendron, huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum), tan oak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus), salal (Gaultheria shallon) and ferns flourish in both. Together they are a paradise for mushroom hunters.

The intriguing thing about these two ecosystems is that they represent a crossover zone between a mediterranean climate and that of the temperate Pacific Northwest. We get no rain from May to late October, but winter rain is abundant. The closed-cone pine forest has many elements of chaparral such as dry, south-facing hillsides and drought-tolerant plants. While the mixed conifer forest exists because of the year-round moisture provided by summer fog and only grows where there is abundant groundwater from creek draws.

Plants have fascinated me since childhood. The unique side-by-side climate zones at Frog Song Farm allow me to choose from a vast plant palette. As long as I am sensitive to the needs of each plant, I can grow a diverse range of plants and indulge my curiosity by finding a balance of Mediterranean plants that can take some water and temperate ones that can stand a bit of dryness.

In addition to learning which plants would thrive, I had to understand local growing conditions. Previously, when I gardened on the San Francisco Peninsula, the climate was as benign and flexible as can be imagined. Here in Point Arena, I’m dealing with three major issues I never encountered in the Bay Area. One is wind. The large open garden within the forest creates a wind tunnel for the spring winds that pummel the coast. Deciduous trees and shrubs hate this drying wind, which peaks just as they leaf out. Or, more accurately, try to leaf out. A small vineyard and many of my favorite trees selected for their fall color failed to look anything but miserable and we either took them out or moved them to more sheltered areas. Second, the wind causes an upwelling of deep ocean water that is characteristic of mediterranean climate zones around the world. A side effect of the cool ocean is that summer temperatures rarely get above 70°F—delightful for humans, but many plants need summer heat to perform well. This was a surprise to me. My salvia collection suffered terribly in the first years at Point Arena, but I did not give up until I found plants that do well here, such as Salvia apiana, S. ‘Waverly’, and S. mexicana.

The third change for me was that I no longer had access to adequate water for irrigation. The property sits on the top of a ridge between the ocean and the San Andreas Fault, and our well requires careful management in the summer months. From the beginning, we grouped plants according to their water requirements and used drip irrigation wherever we could. Sometimes we “borrowed” water from upper areas of the hill, using gravity to let it do double duty for less thirsty plants further down. We built a recirculating creek and planted perennials, hydrangeas, and azaleas around it. In areas without irrigation we added local natives or let volunteers remain where they grew naturally. The hardest decision was allowing the lawn to go dormant in the summer. For 15 years, I have had a brown summer lawn—but with the first rain it greens up almost overnight. It has taken some getting used to, but it was either a green lawn or a green garden. The garden was an easy choice.

Lessons learned

Generally, Southern Hemisphere plants do not mind wind, and deer do not like them at all—a double win. Many New Zealand natives love this climate, especially Leptospermum, Hebe, and Phormium. We grow many varieties of each. I was eager to try the Protea family. Specimens from South Africa bloom well each winter and spring, including tender ones planted on a hillside where frost is rare and drainage is excellent. We have had success with Hakea and Banksia, and great success with Protea, Leucodendron, Callistemon, and Grevillea. All are mainstays throughout the garden for their drought tolerance.

Chilean myrtle (Luma apiculata) forms an allee along the central garden axis and populates the bocce terrace. Rows of lavender flower luxuriantly and fill the air with fragrance. Oregano is a natural; who knew there were so many colorful kinds? All of these plants are magnets for pollinators in the summer. Dwarf conifers thrive with a bit of supplemental water and modest wind protection. Without water, the original white birch trees in the lawn all died, but they have generously reseeded along the pond edge and provide wonderful fall color. I love serendipity in the garden.

On a 150-foot bank, thousands of naturalized daffodils team up nicely with Vitis ‘Roger’s Red’, providing both spring glory (daffodils) and brilliant red fall color (grapes), as well as a sea of lush lime-green grape leaves all summer. Neither needs supplementary water at all. But the stars of our garden are heaths and heathers, which dislike heat so they are perfect for this garden. Close to a third of the area on the clear-cut hill is devoted to Erica varieties from Europe and South Africa and to Calluna vulgaris, Scotch heather. Calluna varieties put on a spectacular display in August and provide year-round foliage color. Erica ×darleyensis blooms from October to March in big drifts of pink and white. South African varieties bloom variously throughout the year. All are beloved by bees.

Old garden favorites and a productive harvest

Dogwood, roses, azaleas, perennials, hybrid rhododendrons, maples, oaks, and succulents are grown in moderation, carefully screened out of the wind and fenced from deer. I will admit that some suffer in dry years, but we do the best we can with targeted hand watering. And vegetables? We have them, too. In abundance since my daughter, the farmer, moved onto the property in 2004 after my husband’s death. She also tends our orchard of apples, pears, cherries, and plums.

The only problem for the veggies is the now-familiar lack of summer heat. After all, what is summer without vine-ripened tomatoes? So we built a large, 1000-square-foot hoop house for squash, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, and other heat lovers. Potted fruit trees like figs, avocado, peaches, apricots, and all kinds of citrus also are grateful for the added warmth and protection. It is a glorious sight, and we eat wonderfully healthy food all year, sharing the excess with a local organic restaurant. Two greenhouses shelter collections of tender tropicals and cactus, as well as serve as propagation centers for seeds and cuttings.

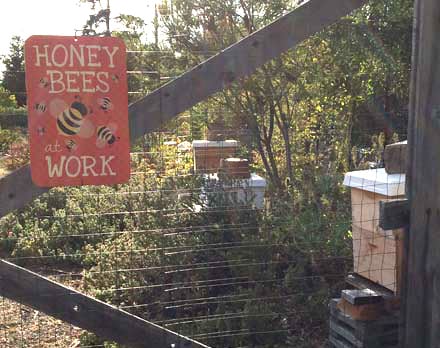

The addition of chickens, rabbits, and beehives rounds out our farming operations. Our hives are doing well. The garden I originally planted is perfect for bees and other pollinators as something is always in bloom—another fortunate serendipity. We have much better orchard pollination and plenty of honey as a bonus. The chickens are the champions of our composting operation and their “product” brings rich green color and abundant growth to the garden. And we do love their eggs. Mulching with local organic dairy manure helps maintain soil moisture through the summer and keeps weeds in check. Ten years ago, we installed solar power to generate all the electricity we use. It is very successful and has saved both money and the environment. I highly recommend it.

But what of those grandchildren I mentioned? There are now 13 of them! Frog Song Farm is a favorite place to visit. Not only do they graze endlessly for food, but they also have a special labyrinth just for their play. Woven hose fences, a bicycle tire tepee, broken surfboard sculpture, and other features constructed out of used materials of all sorts—most headed for the dump—teach them that recycling can be creative too. The centerpiece of the labyrinth, the children’s favorite play area, is an old VW camper turned “art car” turned kids’ playhouse. Scenes of Point Arena cover the outside of the vehicle but imagination reigns on the inside as they plan “trips”, cook “meals”, and create the miracle of childhood.

Our original vision for Frog Song Farm is now collectively held by all the family, including our extended family and friends. It is an expression of the heart as well as the mind and an embodiment of a lifetime of love and nurturing living things.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

In the spring, native frogs warm up their voices and provide us with a symphony of sound for months. It seemed obvious to call our farm Frog Song. In an effort to be responsible and reduce mosquito breeding in the pond we introduced mosquito fish. What I did not realize was that mosquito fish also enjoy frog and dragonfly eggs. The resulting drop in their numbers is a great disappointment, but at least we have few mosquitoes. A word to the wise, take care when introducing anything into a stable ecosystem. I would rather have the frogs.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Responses