Contributor

- Topics: Archive

In 2000, Rancho Los Cerritos Historic Site was awarded a local grant to restore the orchard designed by Ralph D Cornell in 1931. Once the historic varieties were tracked down and installed, the research on the orchard trees was filed away. So many intriguing stories had surfaced in the research process that it seemed a shame to relegate the files to stygian recesses once more. So, in 2005, the lecture Bountiful Harvest was presented to the public, complete with a tour and fruit tasting. The urge to share these stories with a wider audience persisted, and so the following excerpts are proffered for those who enjoy dipping into the past to see how we got where we are today.

Early European settlers in America found existing civilizations already cultivating food crops, including a number of fruit trees, without the technology applied in Europe or Asia. Those early adventurers, settlers, and pilgrims came prepared to plant the new world with seeds of grain and fruits that they had grown in their homelands.

Dreaming of vast riches, the Spanish, English, and French competed for territory on the East Coast. Basic survival was the motivation for planting crops as soon as possible. Compared to earlier civilizations, these settlers had the knowledge and could import manufactured goods to speed colonization, despite the distance from their varied homelands. Settlement met with resistance from the native people, but soon plantations and estates were established, representing the “good life” with the quality of harvests improving and crops hybridized like never before.

The initial European settlement of the southern West Coast was by Spanish missionaries. As each mission was established, the padres planted food crops to sustain not only themselves but the “neophytes” as well. In 1784, San Gabriel Mission’s Padre Principe sent Corenino Agina to Sinaloa, Mexico, specifically to gather seeds, cuttings, and graft wood of various fruits established there. The mission orchards in Southern California thrived; some, such as San Gabriel and San Buena Ventura, truly flourished. Almost every seed or cutting they planted did well—as long as they provided water.

Rancho Los Cerritos

Soon after Spanish settlement of California, pioneers from the eastern US came West, hoping to carve a spot for themselves. Among them was an entrepreneur named John Temple, who purchased the 27,000-acre Rancho Los Cerritos in the 1840s. He wrote to his family in Massachusetts for peach, plum, and cherry stones, as well as other seeds, so he could plant his own orchards and gardens.

Temple also turned to the nearby Mission San Gabriel, which provided seeds and cuttings to many local ranchers. The olives, pecans, pomegranates, figs, grapes, oranges, lemons, limes, and pears originating from the mission gave birth to California’s emerging agricultural industry.

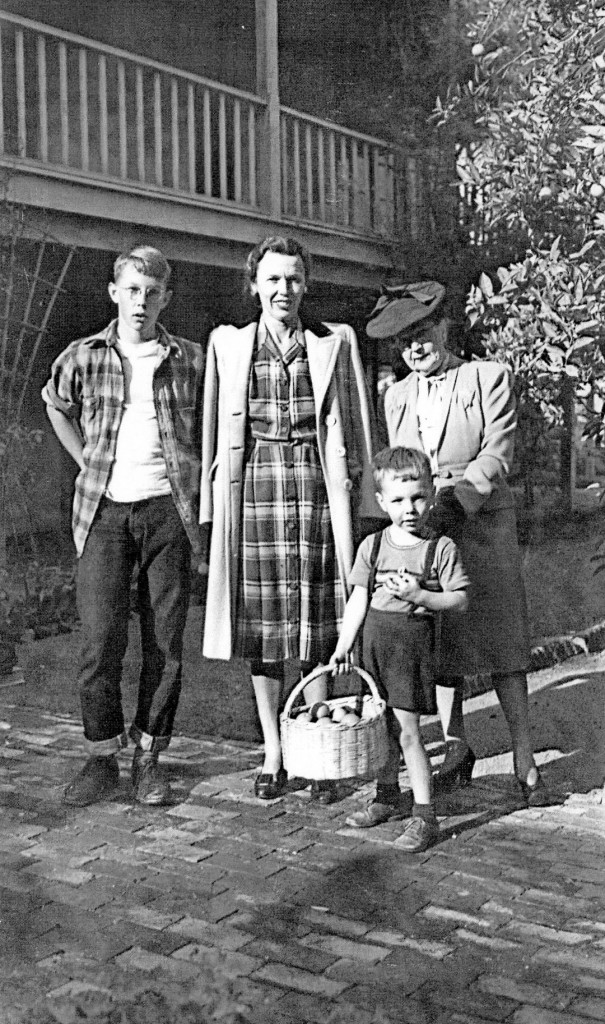

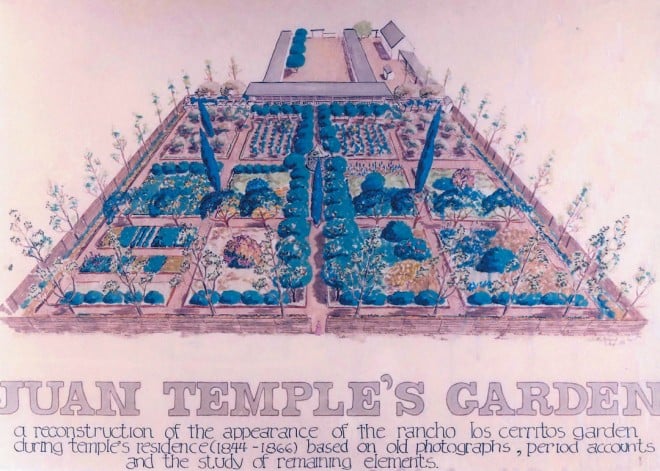

Rancho Los Cerritos was Temple’s headquarters for his cattle ranching operation, but it never served as his primary residence. Still, he built a fine adobe house and created a two-acre garden that was a showplace for the time. In a climate where irrigation was essential, Temple planted not only orchards but also a formal colonial garden, where trees and flowers from his New England youth merged with exotic and diverse plants such as the subtropical citrus and the Mediterranean pomegranate.

Temple sold his property to the Flint, Bixby Company in the 1860s for $20,000. Despite Temple’s claim that the sale price was less then he had put into the garden, the house and garden were included in the sale, and became the Bixby family residence for the next twenty years. We know from written accounts of the Bixbys’ at the time of the sale that “. . . the cherries were the chief glory of the orchard” and that varieties of apples and pears were plentiful. The pomegranates, olives, grapes, oranges, an old purple fig, as well as the stone fruits, became a part of the Bixbys’ daily life, and all of these combined to make a lasting impression on family members. Between 1880 and 1930, the property was leased to tenants, and the gardens suffered. By 1931, little remained when Llewellyn Bixby turned the scant five acres into his personal residence. He communicated his interest in preserving the historic nature of the site to landscape architect Ralph Cornell, who incorporated many of the old trees into the estate garden he designed for Bixby, even as the “Golden Age of Gardening” was coming to an end. Despite the stock market crash and the worsening economy, the Bixbys were able to pursue the development of their property. Cornell’s design was redolent with the history of the site, including options for multiple orchards.

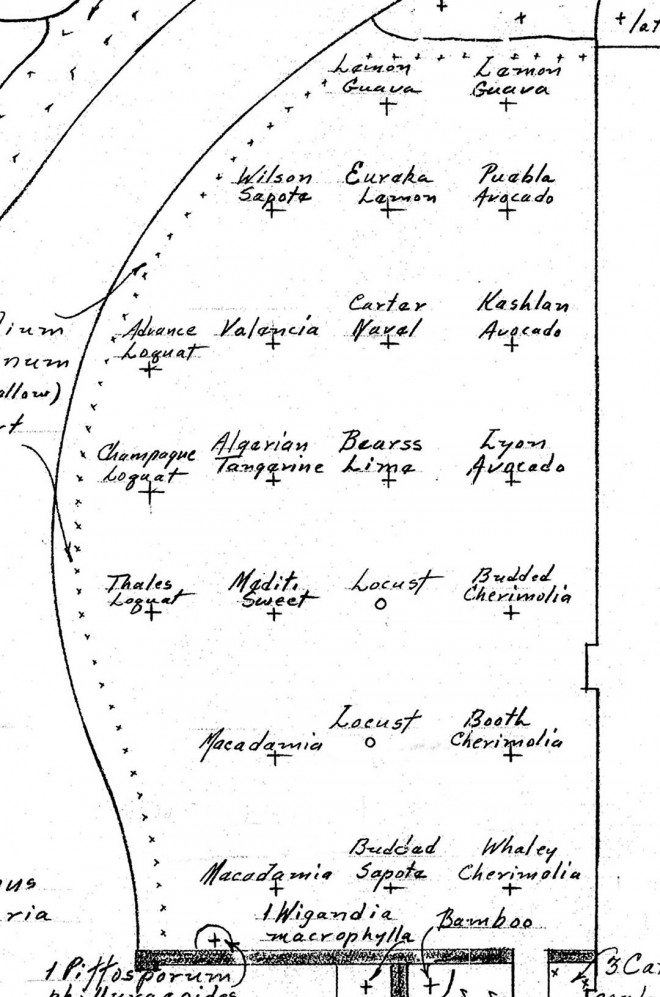

Llewellyn and Avis Bixby were not ostentatious people, and family comfort was more important to them than impressing their neighbors. The plan the Bixbys chose had a modest primary orchard of two dozen trees, as well as a secondary orchard half that size. Another dozen fruit trees, many exotic, were planted within various garden areas. The Bixbys certainly benefited from the activity of hybridizers, and the varieties of fruit trees planted reflected not only some of California’s earliest hybrids, but also the latest and most productive introductions.

After Llewellyn’s death, Avis decided to move into town, but she listened to her neighbors who felt that the property was unique enough that it should be preserved and not developed.

Long Beach Takes on the Rancho

The Bixby family and the city of Long Beach reached an agreement, and the property changed hands for the last time in 1955. The city focused initially on the use of the house, but eventually they wanted to “utilize” the entire site. With an eye to producing income by renting out portions of the garden, they chose to turn the primary orchard into a couple of walled courtyards. Some of the old fruit trees remained, but others were removed and additional trees planted. Sadly, the plan was flawed: construction was poor and the trees failed to thrive in the altered conditions. Soon the courtyards were closed to the public.

Meanwhile, a Mayor’s Task Force had determined that the period of interpretive significance for the historic site should extend from the 1840s beyond the 1870s to the 1940s. This was a significant change, as previous plans did not consider the 1930s modifications to the property to be worthy of preservation. A master plan for the site recommended that elements of Cornell’s estate plan, some of which had been lost, would need to be replaced.

With little funding for research into the historic fruit cultivars from Cornell’s plan, the task was worked into rainy days and other odd moments for several years. Devoted to preserving Long Beach history, the Long Beach Navy Memorial Heritage Association granted funds for the project, and the restoration work began in earnest—including work on the orchards.

The next step was to locate those historic cultivars, some of which had disappeared from the nursery trade long ago. The California Rare Fruit Growers, various university staffs, and numerous propagators and nursery people donated countless hours discussing likely sources for viable historic trees from which scion wood could be obtained, enabling the restoration effort to pursue historic integrity.

The Rancho’s archives included Cornell’s 1931 plan, but his work failed to meet the Long Beach Planning Department’s current requirements. New plans had to be drawn; although this was an historic restoration, the property would have to meet new codes, including updated accessibility requirements. This meant adding a non-historic pathway through a portion of the garden, which resulted in the elimination of a couple of trees from Cornell’s original plan. When he designed this area, it had two existing black locust trees (Robinia pseudoacacia); long gone, they were not replaced in the restoration phase.

Demolition began in 2001, and years of dreaming became reality. Occasionally the dream took on a nightmarish quality, as protecting the historic trees from the demolition teams became a major task. But eventually the rubble was hauled away and the dust settled. The remaining trees included four citrus, two avocados, and one cherimoya. Eliminating the two locusts meant there were now fifteen trees to locate and replace in fulfillment of Cornell’s 1930s plan.

In researching the historic orchard trees, it was easy to get caught up in the tales of the individuals involved. It is these stories that I would like to share with you in upcoming issues of Pacific Horticulture: the stories of the trees and the people who developed them.

The author will begin her stories of the historic orchard trees of Rancho Los Cerritos in the next issue of Pacific Horticulture.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Responses