Contributor

- Topics: Archive

In 1959, Marshall Olbrich and Lester Hawkins left professional careers and a San Francisco apartment to homestead three acres of pastureland 70 miles north of the city in rural Sonoma County at a time when affordable land attracted legions of disaffected city-dwellers seeking a different lifestyle. Western Hills, their refuge from urban politics and stress, was named after the early Chinese philosopher’s retreat outside Beijing and evolved into an enterprise that inspired a community of horticulturists and landscape designers that profoundly changed the look of West Coast gardens.

The tiny town of Occidental lies in a narrow valley where the redwood-clad inland slope of the Coast Range meets rolling orchards and vineyards nine miles west of Sebastopol. The area enjoys a temperate mediterranean climate with six months of drought followed by an average of 60 inches of winter rainfall. Marshall described their land about a mile west of town as “a sort of bent rectangle sloping gently to the east but with a decided rise at its western boundary.” Coast redwoods crowned the rise. Thick rushes crowded a boggy lower meadow. In the first couple of years, and with the help of friends, the partners built two rustic houses and a barn. They dug drainage ditches and ripped out poison oak and blackberries to plant fruit and nut trees and a vegetable garden.

To supplement their income, Lester commuted to the city to drive a taxi and Marshall worked at a Sebastopol nursery. Inspired by the horticultural delights of Strybing Arboretum (now San Francisco Botanical Garden) the partners began replacing the homestead’s edible plants with an exotic palette of Australian, Chilean, and South African trees and perennials with little appreciation for their eventual size or adaptation to the long summer drought. After Lester began designing gardens professionally, including the Bancroft Garden in Walnut Creek, they opened Western Hills Rare Plant Nursery in 1973 to support the business and sell to the public.

Disaster struck in December 1972 when temperatures below 20°F for several days destroyed tender plants across Northern California. After losing nearly one third of their plants, the garden and nursery recovered after repopulating with hardier species of drought-tolerant and California native plants. These included Arctostaphylos, Artemisia, Baccharis, broom, lavender, rosemary, rockroses, and Phlomis, one of Marshall’s favorite plant species, determining through trial and error which plants were best adapted to local conditions.

Growing a community

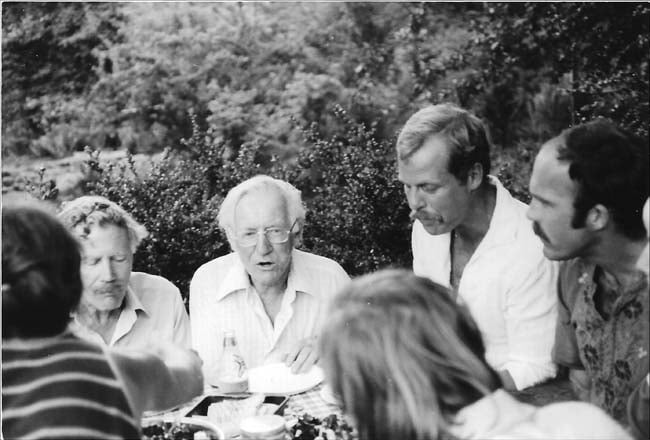

Both men attended meetings of the California Horticultural Society where Lester started a native plant study group and Marshall established a reputation as a knowledgeable plantsman. Their academic approach to botanical studies and a collegial willingness to share their knowledge attracted a younger generation who trooped up to Sonoma to learn from their mentors. Former Peace Corps teachers and future landscape designers Bill Day and Jim Hickey moved into the barn and worked at the nursery for several years. Betsy Flack recalls convivial dinners late into the night where Lester held court on topics from economics and politics to literature, philosophy, and art. Writing in Pacific Horticulture in 1991, Chris Rosmini spoke of an enjoyable blend of shoptalk and salon that “encouraged a lot of us to believe that perhaps we too could create good gardens and live lives we chose.”

Visitors arrived from around the world to exchange ideas, swap seeds and purchase from an expanding catalog of unique species from mediterranean climate regions. According to Ginny Hunt, the nursery’s propagator, “before the internet, finding such plants could be a real challenge.” At Western Hills, customers could view and then purchase a wide variety of plants from a garden setting. Neighbor Bob Hornback recalls their unique offerings of variegated foliage.

Lacking a formal landscape plan, by the late 1970s the overplanted garden matured into dense woodland. Paths meandered through towering conifers and mature deciduous trees revealing a variety of habitats and separate garden worlds. Lester’s eclectic mix of bulbs, shrubs, and hardy perennials formed a rich understory of layered plantings in unexpected textures and colors in a naturalistic, plant-driven style. Thirty-four wooden walkways and bridges, many with Asian detailing, provided access over the drainage channels to several ponds and the lower garden.

Impressed with Lester and Marshall’s horticultural knowledge, Roger Warner abandoned his pursuit of a PhD and joined the partnership in 1980. Marshall credited his energy and creativity as having a “profound effect on both garden and nursery.” Roger supervised the construction of a propagating house and digging a deeper well; these improvements expanded sales to a level that made the nursery profitable. And after several collecting trips to England with Marshall, Roger, aided by visiting plantsman, author, and Kew Gardens curator, Brian Halliwell, created a perennial border in the lower garden to display the new plants in a garden setting.

Lester, who was never that interested in the business of the nursery, devoted himself to traveling and writing about plants and gardens appropriate to a mediterranean climate. Through 14 of his articles that appeared in Pacific Horticulture, ideas developed at Western Hills have greatly influenced today’s approach to working with drought-tolerant landscapes. Ten of these stories appeared in The Pacific Horticulture Book of Western Gardening, where editor George Walters acknowledged that Lester “did more than most to establish the tone and authority of the magazine.” Following a trip to Turkey, Lester fell ill. Shortly before he died in 1985, he told English gardening legend Beth Chatto, “The plants have been good to us.”

Roger Warner left in 1984 to start his own landscaping business that included working with Jane Davenport Jansen, founder of Quarryhill, but Maggie Wych, an English transplant and former craft jeweler he had hired as a “water woman” in 1982, stayed on. Marshall continued the partners’ 35-year tradition of seeking out new plants and sharing them generously with all who entered within the gates. Although the demands of maintaining a garden that had achieved the status of a living national treasure weighed heavily on him, in his last letter to Chris Rosmini Marshall exclaimed, “The garden has never been more photogenic! Boy! The plants I got. Come up and see!” He died of a heart attack in 1991.

Preserving a Horticultural Heritage

Marshall left Western Hills to Maggie, who continued the founders’ vision of a tranquil setting where plant lovers can enjoy and purchase rare species. With no formal training in horticulture, Maggie educated herself through extensive reading and conversation with the legion of professionals who crossed paths at the nursery. She put her own imprint on the garden by opening vistas that had become congested over the years. After heavy rainfall damaged the center of the garden in the 1997-98 season, she supervised a two-year effort to line the main water channel with stabilizing rocks that have mellowed into an attractive feature of the property.

Maggie added new California natives as well as varieties from China, Mexico, and beyond, to Western Hills’s inventory, but faced increasing competition from more easily accessible and larger vendors. Many rare species of the 1970s were widely available by the 90s. After 15 years of managing the nursery in a manner that preserved the legacy of the founders, when Maggie put the property up for sale, many in the horticultural community feared it would be developed as a trophy home site and access to the public would be lost.

Local residents Robert Stansel and Joseph Gatta purchased the nursery in 2007 with hopes of ensuring the future of Western Hills as a non-profit public garden and educational resource. When the economic recession dashed their plans, the property fell into foreclosure in 2009 and Western Hills entered its “Secret Garden” phase. Unattended, tender plantings withered, vines wound into the canopy, moss carpeted the bridges, and the ponds stagnated. Except for a stealth crew of locals who organized to water the most valuable specimens, as at Misselthwaite Manor, no one ventured beyond the locked gate.

Christine and Tim Szybalski purchased the property in 2010, and began the task of returning the garden to its former glory, which was once described in the New York Times under the headline “If Tiffany Sold Plants.” With a goal of preserving the garden for future generations, Chris, co-owner of Westbrae Nursery in Berkeley, and Tim, a management consultant, made plans for opening the garden for tours and events, establishing a membership program, and reenergizing the nursery’s historic role of introducing new cultivars to California.

Aided by volunteers and advised by professionals, the herculean rehabilitation began. Garden manager Stacie Miller, a member of the clandestine watering crew, was hired to begin a propagation program and coordinate volunteer efforts. “Cataloging the thousands of cultivars we uncover, some days it feels like I’m pursuing a PhD in botany,” she said. Tim’s favorite example is a rare, seven-foot tall Puya alpestri, a June-blooming bromeliad from Chile with turquoise flowers and bright orange stamens.

In 2012, with a new irrigation system in place, bridges secured, trails cleared, and 12 tons of trimmings and weeds removed, the first public visitors enjoyed the garden. Since then, dozens of garden clubs have visited, members have attended fundraising events, and artists have enjoyed special open days.

In 1984, Marshall Olbrich commented to English geranium expert Alan Robinson that “Nurseries are like stars in the sky, they gradually get brighter, twinkle, and then go out.” Garden enthusiasts around the world can give thanks that Western Hills’ star once again twinkles brightly among the verdant foothills of western Sonoma County.

References

Ken Druse. “If Tiffany Sold Plants” New York Times (May 12, 2005)

Chris Rosmini. “Marshall Olbrich, 1920-1991” Pacific Horticulture v. 52, no. 4 (January 1991)

Rosemary Verey. The American Man’s Garden, Bullfinch (1990)

George Waters. The Pacific Horticulture Book of Western Gardening, Godine (1994)

George Waters. “The Days of Compost and Conservation” Pacific Horticulture v.61, no. 3 (July 2001)

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses