The Dunn Gardens

Contributor

In 1914, Arthur and Jeanette Dunn bought a 10-acre parcel in north Seattle for use as a summer retreat. In 1915, the Olmsted Brothers firm was hired to design the garden, and by 1916 it was declared “finished.” I think we all know a garden is never truly done. When Arthur and Jeanette’s children inherited the property they evenly divided it among themselves and the once-seasonal getaway became three year-round residences. Edward Bernard Dunn, their second son, converted the garage/staff building into a home and began gardening.

Ed adopted a relaxed Robinsonian approach to his mostly wooded site furnished with Douglas-fir. His love of rhododendrons was paramount and, over time, he filled his garden with them. When the easy-to-plant areas were filled to overflowing, Ed managed to shoehorn even more in. This was not always the best thing for the plants, but I think most of us can relate to plant lust. Toward the end of his life, Ed worked on preserving the future of his 2.5-acre garden as well as the two adjoining properties owned by his siblings. The E.B. Dunn Historic Garden Trust was established to care for the entire 7.5 acres.

Charles and I first met Ed and “discovered” the Dunn Gardens in 1985 when we were asked to help replant an area after some septic system work was done. As we drove away at the end of the job I mentioned to Charles how remarkable it was to find an oasis like this within the city limits. And wouldn’t it be wonderful to live there? Ed passed away in 1991. In 1997, 12 years after our first encounter with the Dunn Gardens, we were hired to be curators/caretakers of the property and moved into Ed’s charming—if drafty—house.

Our work here involves both curating and caring for the Gardens. Our first years were spent removing noxious self-sowing plants. Even now, if we got a dollar for every unwanted seedling that popped up year after year, we’d have a much bigger budget for desirable plants!

The Dunn Gardens are listed on the National Historic Register, a designation that brings both pluses and minuses. Like the Bible, the document’s actual meaning may be interpreted in many ways. Early restrictions were onerous. Fortunately, the Trust’s board of directors formally adopted the National Park Service approach for Historic Landscape Conservation. And over time we’ve been given more freedom when an area needs to be renovated or rehabilitated.

Ed’s keen eye for plants meant the Trust inherited a beautiful collection including luxurious swaths of Erythronium revolutum. Like diamonds, a girl can never have too many Erythronium—or Trillium! We’ve divided congested clumps of these specimens, many untouched for decades, to create large drifts throughout the woodland.

Yes, Ed loved rhododendrons. However, after living with hundreds of them for the last 17 years, my fondness for some of them has greatly diminished. The ones with exceptional foliage still bring a smile to my face. Others, meh… Yet during April and May when the garden is in a full-tilt-boogie flowergasm, it’s pretty spectacular.

Ed often traveled, enjoying hiking and sailing, after the spring show was over so summer color was limited. But with garden tours offered April through July, September, and October, and special events held throughout the year, we knew we needed to extend the seasons of interest.

Working beneath 100-year-old deciduous trees and towering Douglas-firs requires a different skill set than designing a garden on a newly developed residential lot. We planted a woodland walk with a backbone of mop-head hydrangeas in a former laundry yard devoid of plants. Though beautiful in flower, we realized that watering the thirsty plants during the warm months wasn’t good for the firs overhead. So out came the hydrangeas, which were moved to an area where they could receive ample irrigation (fortunately we’re on a well). For similar reasons, early on we removed turf from around the firs in the Great Lawn. By enlarging the beds and establishing more xeric plantings, we were able to reduce irrigation that was threatening the trees.

Working with scale at the Gardens can be humbling. Witch hazel (Hamamelis spp.) and Japanese maples (Acer palmatum) were added to the landscape for autumn color. But we often began with one- or two-gallon sized plants to avoiding chopping into the root systems of the large trees. It will be many years before these young plants mature and fill in among the neighboring 150-foot-tall trees.

Taking care of the trees has been our biggest challenge. Many of the eastern U.S. native deciduous trees appear to have plateaued; a few lovelies have been taken down, and more are in decline. It has been difficult convincing well-meaning people that replanting a tree where one has been lost isn’t always the best idea. Beyond hygienic reasons, the earlier trees grew up together and developed their grand character in a more open environment. It’s not realistic to expect a sapling to grow in a balanced way in the shade of towering neighbors. We have successfully argued to wait and replace critical Heritage trees only when there is an opening in the canopy that will support a young tree’s proper development.

We are also reducing the numbers of native conifers whose size and spread threatens to overwhelm the parkland character of the Gardens. While they are an integral part of the Gardens, editing their rapid growth requires careful curating over time as they attain gigantic proportions.

[sidebar]The Dunn Gardens

13533 Northshire Road NW

Seattle, Washington 98177

www.dunngardens.org[/sidebar]

Over time Charles and I have worked with the Trust board to develop an understanding of the dynamic interplay of the Dunn Gardens’ original design and existing plantings with the environment and the passage of years. Do plan on stopping by in 2015 as we start on our second century! And visit the website to read more about plans for sustaining the Gardens over the next 100 years.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

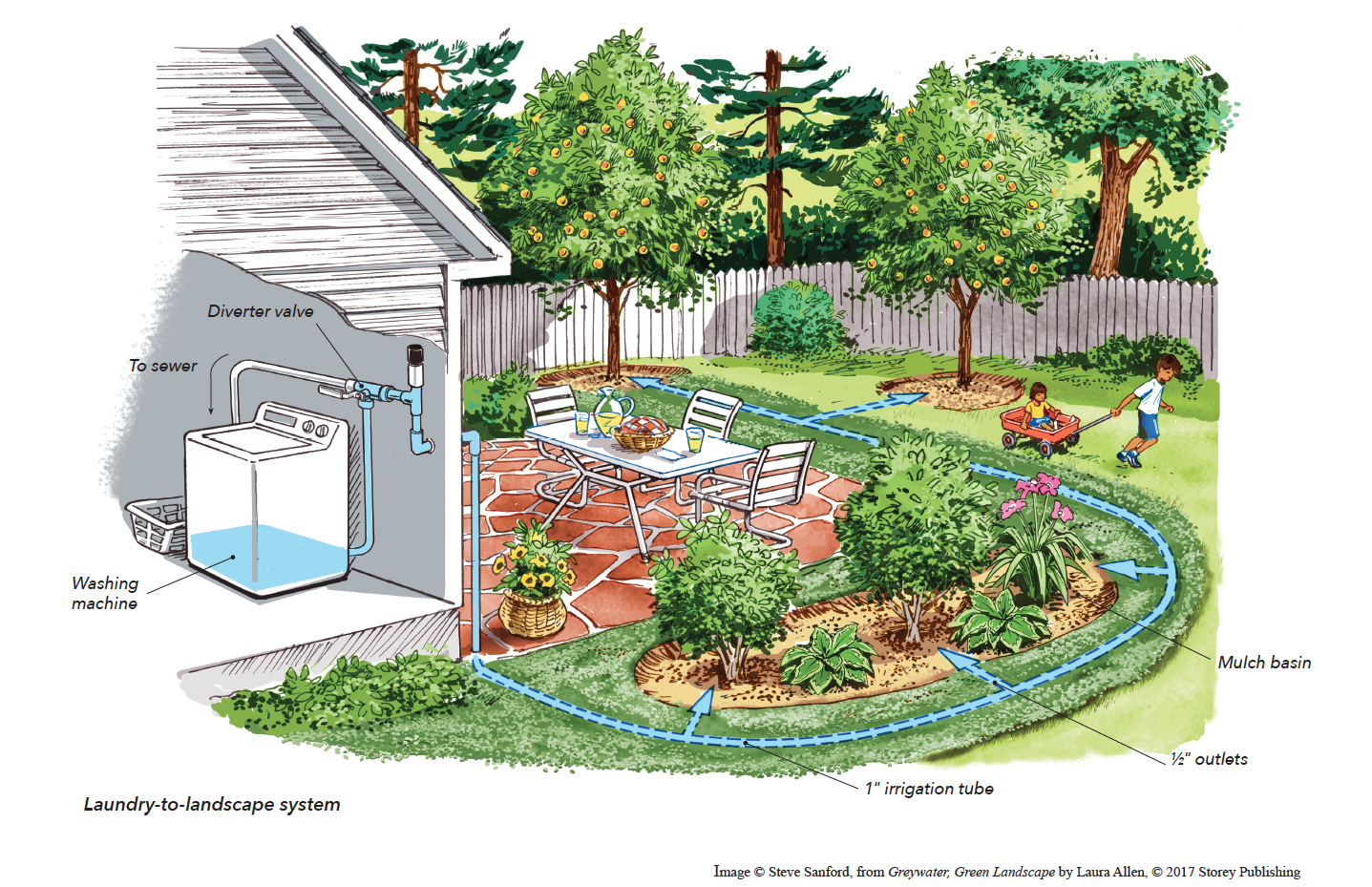

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses