Contributor

Vine Hill manzanita is the source of some of the most widely planted and adaptable native cultivars in California, yet the species is one of the rarest plants in nature.

In the 1800s, early settlers in Northern California’s Sonoma County found the gently rolling sand hills of the Vine Hill area, between the towns of Sebastopol and Forestville, to be ideal for orchards and vineyards. When Santa Rosa Junior College botanist Milo Baker first described Vine Hill manzanita (Arctostaphylos densiflora) as a new species in 1932, he stated that it was “probably a relict in a region where natural vegetation is fast disappearing through an intensive system of agriculture.” (Four Seasons, page 2, May 1972) By that time, according to Baker, Vine Hill manzanita had been reduced from an unknown pre-contact population to about a hundred individuals along a narrow strip of Vine Hill School Road, and about six plants on nearby Vine Hill Road. There may also have been one or more plants of the species in the Freestone area, about eight miles to the southwest.

James Roof, former director of Berkeley’s Regional Parks Botanic Garden, was much taken by the beauty of this new species of manzanita and wrote in flowery prose of his first visit to the type locale:

My first view . . . was on a winter day in 1940. The Manzanitas were in rose colored bloom, and complementing this were the sky blue flowers of Ceanothus foliosus var. vineatus. Most of the Ceanothus though, was in bud, the red flower-bracts blending enchantingly with the blue flowers. Low shrubs both, in places the two species sprawled into one another, making a mix of colors in the sunlight that was too gorgeous to take. The warm air hummed with legions of bees at bumble. The roadside strip was then about fifteen feet wide and several hundred feet long. The road’s north facing flank was a long sand slope, and the plants tumbled down it in blooming profusion, ending only at the cultivated margin of a vineyard a hundred feet below. The last remnant of the Sonoma Barren was a very lusty remnant indeed. (Four Seasons, page 5, May 1972)

This reference to the “Sonoma Barren” reflects Roof’s observation that Vine Hill manzanita’s habitat shared many similarities with the pygmy forest “barrens” of coastal Sonoma and Mendocino counties. The sandy-clay soils of Vine Hill (compact argillaceous sands), are pale yellow to nearly white and distinctly acid. Vine Hill manzanita often grows widely spaced, with moss and lichens growing on the ground between, much as Arctostaphylos nummularia grows in the Mendocino Pygmy Barrens. At least two species growing in association with A. densiflora also link it with the Pygmy Barrens: bear grass (Xerophyllum tenax) and salal (Gaultheria shallon).

In subsequent visits to Vine Hill School Road, Roof witnessed numerous assaults on the roadside flora. He writes of a visit in 1947:

Though the manzanitas were in full bloom, there were no bees working the shrubs for honey. The strip had overnight become an ecological disaster area. Sonoma County road crews had dripped used crankcase oil over the road margin in an experimental program designed to employ used oil as a “control for roadside weeds and brush.” The oiling had been done the day before; the black sludge still oozed from some of the rose and blue flowers. No savages would have been so heedless of beauty; it was an act of morons. (Four Seasons, page 6, May 1972)

Work crews at one point completely denuded this same roadside of vegetation, even raking it clean. After World War II, it was “bladed off” at least once. A protest from Santa Rosa Junior College and growing neighborhood awareness of the rare manzanita slowed the destruction somewhat. Subsequently, the driveways of two newly constructed country homes wiped out another portion of the colony, and in 1957, the farmer owning the land scraped a wide swath. All of this so profoundly affected the manzanita that, by 1963, Roof notes there were only “two shrubs and one not a good one.” (Four Seasons, page 7, May 1972) Returning in 1967, Roof was “agreeably astonished to discover fourteen two- and three-year-old shrubs on the slope that, a long time back, had been so much disturbed.” (Four Seasons, page 7, May 1972) This regeneration had occurred on the bare soil exposed by the 1957 scraping, ten years earlier.

It appears that, to some degree, Arctostaphylos densiflora thrived on the bladed and scraped roadside and hill. The scraping by heavy machinery probably scarified seed in the soil’s seed bank. On his first visit to Vine Hill, Roof observed plants that had germinated in cleared soil. In 1932, Baker wrote, “Since these road banks are apparently not very old, one wonders where this species maintained itself before the present banks were graded.” (Four Seasons, page 7, May 1972) Perhaps, in earlier times, Native American land management through burning had provided clean and open sites for the manzanita’s renewal and regeneration.

After visiting the Vine Hill School Road site in 1971 and noting a modest recovery of the manzanita (forty-five plants), Roof devoted the May 1972 issue of The Four Seasons, the Journal of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden, to the history, evolution, and biology of the Vine Hill manzanita. In that issue, he made an eloquent plea for the permanent preservation of the Vine Hill manzanita through the creation of a preserve. It was this act that led to the purchase of the property by The Nature Conservancy and the deeding of the property to the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) for the creation of the Vine Hill Preserve, home to the world’s entire remaining population of “wild” Arctostaphylos densiflora.

The Current State of the Preserve

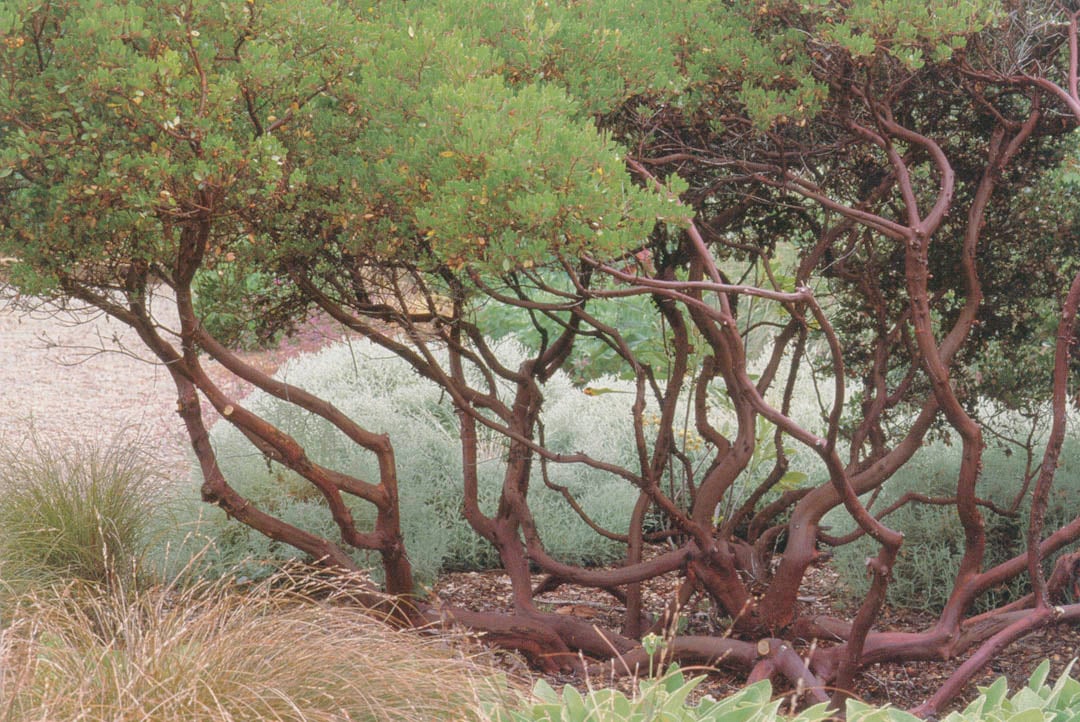

Beginning in 1982, as preserve manager, I took cuttings from many individual plants of Arctostaphylos densiflora on the preserve, rooted them, and planted them out from gallon containers during the following winter. In order to avoid unforeseen problems that my plantings might create, I always planted in the lower disturbed portion of the preserve. I generally utilized the mounds remaining from grape cultivation, typically planting in November or December after soaking rains. The new plantings sometimes received a little watering at planting time, but never again. Since the lower portion of the slope has good sun exposure and has been free of manzanita pathogens, the plantings have thrived. Some of these early plantings, now twenty years old, have a fifteen-foot diameter and a lovely bell-shaped center with a broad skirt of prostrate growth. They form a natural appearing drift of healthy low shrubs, looking like they might be more at home on coastal dunes than in the mixed evergreen forest of the Forestville area, a full thirteen miles from the sea.

Since the early 1990s, Jay Pedersen has been preserve manager. He has been successful at involving volunteers in the ongoing maintenance necessary to prevent the preserve from converting to a mixed evergreen forest, dominated by coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia, and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesi). This consists of cutting seedling oaks and firs at ground level and sometimes treating the oak stubs to prevent them from vigorously re-sprouting. His work also includes discouraging exotics, especially Spanish broom (Spartium junceum), as well as continuing the planting of young, cutting-grown manzanitas.

In his article urging creation of a preserve, Roof made several suggestions for its management, including the introduction of the rare local endemic annual, Clarkia imbricata. As he suggested, members of the Milo Baker Chapter, CNPS, introduced the rare clarkia to the lower portion of the Preserve, an area dominated, at the time, by weedy non-native grasses and old grapevines; there it has persisted and thrived despite competition from exotics. Roof personally introduced two seedlings of Navarro ceanothus (Ceanothus gloriosus var. exaltatus) from nearby Guerneville Road. Subsequently, Jana Niernberger and I added more seedlings of that ceanothus from the same source. Again, these introductions were placed in the highly disturbed lower portion of the preserve. These plants have mostly become senescent or died, but their seedlings are growing to replace them.

The Type Cultivar

In the early 1940s, Professor Baker was irked that Arctostaphylos bakeri was being sold by some Santa Rosa and Petaluma nurserymen as A. densiflora. In 1941, Professor Howard McMinn and Maunsell Van Rensselaer, director of Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, visited the site of the future preserve, along with Dr Rimo Bacigalupi, Dr Herbert Mason, Louis Edmunds, and James Roof. Baker proposed that they select a type cultivar of Vine Hill manzanita, endowed with the finest ornamental qualities of the species. McMinn and Van Rensselaer were completing their masterwork, Ceanothus, and had assembled this impressive team to help clear up some questions regarding taxonomy in the genus Ceanothus. They were visiting the Vine Hill area to see Ceanothus foliosus var. vineatus; only incidentally was the type cultivar of A. densiflora chosen and cuttings taken by Edmunds.

Recalling this event of 1941, Roof wrote in 1972,

On the slightly elevated margins of the heath were found two subshrubs, one the rare Vine Hill Ceanothus, Ceanothus foIiosus var. vineatus . . . [and] a splendid form of A. densiflora that can reach three feet in height but usually sprawls at two. Because of its abundance of rose-colored flowers, this multi-bloomer was long ago selected as the cultivar type of the species. (Four Seasons, page 4, 1972)

In the same year, Vine Hill manzanita received an Award of Merit from the California Horticultural Society.

It is somewhat ironic that one of the rarest and most endangered species in the genus Arctostaphylos has given rise to so many useful and adaptable progeny. I have stated that Arctostaphylos densiflora is an adaptable plant, but that is not entirely true; this species is really happiest on its native sandy soils in the Sebastopol-Forestville area and often sulks elsewhere. Its hybrids, however, are unusually disease resistant, garden tolerant, and widely adaptable.

Arctostaphylos densiflora ‘James West’ appears to be a selection of the pure species, not hybridized with any another species. As such, it is smaller than most of the other cultivars—about eighteen inches by six feet in ten years. It flowers from January through March with thick heads of small, shell pink flowers often covering its dense, shiny, light green foliage. James Roof, however, felt that its small, acutely tipped, yellowish-green leaves more closely resembled those of A. bakeri than typical A. densiflora. He also suggested that its dark red bark is similar to A. bakeri. Roof’s garden experience with this clone suggested that it was more stable in cultivation, thriving in garden situations that were hotter and more open than other selections.

Hybrid Selections

Nurseryman Louis Edmunds specialized in manzanitas and, in the spring of 1949, presented a group of seedlings to Howard McMinn, professor of botany at Mills College in Oakland. Planted on the college grounds and at the professor’s home, each developed individual characteristics of form and foliage. McMinn suggested that the Saratoga Horticultural Foundation test several forms that had impressed him, with a view to possible introduction. The results of this trial were to have lasting impact on California horticulture. Three of the cutting-grown progeny of these seedlings were subsequently named: Arctostaphylos densiflora ‘Howard McMinn’, California Horticultural Society Award of Merit 1956 and one of the most widely planted manzanitas in the state; ‘Sentinel’, less popular than ‘Howard McMinn’ but frequently grown; and the seldom seen cultivar ‘Harmony’. Though attributed to A. densiflora, all three are actually hybrids with one or more other species.

Early references to ‘Howard McMinn’ refer to it as Arctastaphylos stanfordiana x densiflora. Various authors, including Dr Joseph Adams and James Roof, noted A. stanfordiana in the Vine Hill area. Roof mentions

. . . a peculiar form of A. stanfordiana—white-flowered, upright, and eight feet tall—living at the barren’s margin near the southwest end of the School Road. . . . We term the form “Vine Hill stanfordiana” and cultivate it in this botanic garden [Regional Parks]. Although its shiny leaves do not very much resemble those of typical A. stanfordiana, its habit is practically the same, and it has the typically thin, delicate, “beaded,” upright rachises and the small and remote keeled bracts of typical A. stanfordiana. (Four Seasons, page 11, May 1972)

At times, he also called it the “woodland stanfordiana,” because of its ability to grow at woodland margins.

Botanist Philip V Wells, author of the treatment of manzanita in The Jepson Manual (1993), first identified Arctostaphylas bakeri subsp. bakeri in the Vine Hill area ” . . . on disjunct island of serpentine in Occidental-Camp Meeker belt; also isolated at Vine Hill on sandy clay.” (The Four Seasons, page 66, December 1988) Indeed, Wells identified A. bakeri subsp. bakeri on the preserve itself, estimating the plant to be thirty years old; it seems that every Arctostaphylos expert in the last thirty years has visited the tiny preserve and missed a second rare species of manzanita.

Common manzanita (Arctostaphylos manzanita) is also found on the preserve, and it is primarily these three species—A. densiflora, A. manzanita, and A. bakeri—that form a swarm of hybrid manzanitas along Guerneville Road. Yet, A Flora of Sonoma County (1996), under the heading of A. densiflora and the Vine Hill region, notes that “A strange assortment of manzanitas of varying sizes, some with basal burls and some without, grow in the area (especially along Guerneville Road between Laguna and Vine Hill roads) as a result of hybridization.” Arctostaphylos glandulosa is the only manzanita listed in the flora with a basal burl, which seems to indicate that A. glandulosa must also have joined the mix at some point.

No one knows for certain where Edmunds got the Arctostaphylos densiflora seeds or seedlings he grew and gave Professor McMinn. Steve Edwards, current director of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden, suggests that they could have come from a single shrub in the Edmunds’ Nursery (where many species of manzanita were grown and could have crossed naturally). It is equally likely that they came from the hybrid swarm along Guerneville Road; that roadside area and the Vine Hill Preserve are the only sites in the wild where these three highly compatible species grow and hybridize. The characteristics of the cultivated forms (foliage color or texture, plant size, and garden tolerance) are readily attributable to a combination of the individual qualities of these three species. The mixing of genes was greatest along Guerneville Road, providing more opportunity for varied characteristics.

Decades of county roadside maintenance along Guerneville Road, unfortunately, has mirrored the situation along Vine Hill School Road; cutting and herbiciding has nearly eliminated the manzanitas, allowing and perhaps encouraging the invasion of weedy Acacia and broom.

Of the other two named selections from Edmunds’s seedlings, ‘Sentinel’ is notable for its decidedly upright growth to six feet with an eight-foot spread. ‘Harmony’ is similar to ‘Howard McMinn,’ but with larger leaves and it is slightly larger overall. This may indicate the influence of Arctostaphylos manzanita.

Louis Edmunds made at least two selections, ‘Lynne’ and ‘Monica’, directly from the Guerneville Road population; both appear to be hybrids between Arctostaphylos densiflora and A. manzanita. In 1989, California Flora Nursery received a plant of ‘Lynne‘ from Bart O’Brien, then at Yerba Buena Nursery. He had taken cuttings from a plant about thirty years old in Dr Leo Brewer’s garden in Orinda, east of the Berkeley hills. This clone looks a great deal like ‘Howard McMinn’, growing five to six feet tall and wide, though usually wider than tall. It has glossy green leaves, similar in size and color to ‘Howard McMinn’, with pure white flowers.

At the same time, the nursery also received a plant of ‘Monica’. This cross favored its Arctostaphylos manzanita parentage for its vase-shaped form, reaching fifteen feet tall after about thirty years in the Brewer garden. It has shiny green leaves like A. densiflora but the size and shape of A. manzanita, large pink flowers with just a hint of white, and the very dark trunk of A. densiflora and A. bakeri.

Neither of these cultivars is much seen in the trade, but I think ‘Monica’ shows great promise as a garden tolerant and disease resistant alternative to Arctostaphylos manzanita ‘Dr Hurd’.

Another worthy though obscure hybrid is occasionally available in nurseries under the name ‘Lutsko’s Pink’. It was grown in the Greer garden in Lafayette, California, and was introduced by the garden’s designer, landscape architect Ron Lutsko. Although its origin is otherwise unknown, ‘Lutsko’s Pink’ is a lovely A. densiflora hybrid growing densely upright to four feet or more tall with glossy green leaves and copious clusters of pink-blushed flowers.

By the time I became preserve manager at the Vine Hill Preserve, the small population of Arctostaphylos densiflora on nearby Vine Hill Road had already disappeared, and I never had the opportunity to see it. Roof wrote in the February 1980 issue of The Changing Seasons that, in 1974, he and several friends dug a manzanita seedling from this site at the edge of the road’s macadam to save it from the county road-scrapers. He noted that it was the most unusual manzanita he had ever grown, no small claim for a man who loved manzanitas in general and developed a native plant botanic garden.

This natural hybrid is such a charming little shrub that I gave it the name ‘Ariel’. Though it is a dwarf it is an erect, not a prostrate dwarf, reaching twenty inches tall. . . . This unique Arctostaphylos has yet to be photographed in full bloom. The density of var. densiflora bloom waxes paltry beside it. So floriferous is ‘Ariel’ that, in February or March, there is little room for leaves on the miniature shrub. The flowers are white urn-bells, streaked with pink lines and bearing showy maroon-colored sepals. The bark is as smoothly dark as that of A. bakeri.

Roof harbored some anxiety that the hybrid might be weak:

I have never been certain that it is genetically strong enough to survive in general or even professional cultivation. The original shrub, though well-watered and partly shaded, perished in summer heat on a rocky-well-drained soiI. Two of its progeny, planted in a softer, richer soil, survive in the . . . Regional Parks Botanic Garden . . . If it is a weak hybrid, if it cannot cope with neglect and dies, we shall not see its like again.” (The Changing Seasons, page 15, 1980)

Roger Raiche, formerly of the UC Botanical Garden, Berkeley, made a selection from the Vine Hill Preserve sometime in the 1980s. The plant he selected was an upright dwarf, which he subsequently named ‘Baby Bun’. I have lost track of the parent plant at the preserve, and the cultivar is not being propagated commercially, to my knowledge. There are, however, several specimens of this clone at the UC Botanical Garden.

It is remarkable that a plant with such a restricted range has touched the lives of so many of the great California botanists and horticulturists. I hope that lingering mysteries regarding its origin and evolution will continue to inspire research. The great beauty and genetic diversity of Vine Hill manzanita and its hybrids insure that it will continue to play a prominent role in California horticulture.

Steve Edwards, director of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden, provided invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article.

The Four Seasons is a publication of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden, Tilden Regional Park, Berkeley, CA 94708. The Changing Seasons was published briefly by James Roof.

James West and His Manzanita

James West was the American pseudonym taken by the eccentric and enigmatic German nobleman whose true name and title was Egon Victor Moritz Karl Maria, Prinz van Ratibor und Corvey, Prinz zu Hohenlohe-Schillingfurst. He lived and worked for a time in California in the late 1920s and 1930s, when he helped to develop the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden’s cactus and succulent garden. He botanized and collected in South America for the garden and developed close friendships with prominent figures in the Bay Area, including horticulturist Victor Reiter and photographer Imogen Cunningham. A relatively minor footnote to his intensively active and productive life in California was his discovery of the ‘James West’ cultivar of Arctostaphylos densiflora.

West was living in a tent in the backyard of a boardinghouse in San Rafael, in spite of the fact that he had ready access to the family fortune in Germany. In his spare time, he would take botanizing trips to Sonoma County. On one of these trips he discovered the manzanita that now bears his name. He gave a start to botanist Robert H Menzies, also living in San Rafael, who then passed it on to nurseryman Louis Edmunds and into the trade.

West disappeared during the 1936 UC First Expedition to the Andes, never to return to California, and never to clarify exactly where his manzanita was found. Whenever questioned on the source of this plant, his answer had always been “Bodega.”

Much effort by botanists and horticulturists failed to turn up Arctostaphylos densiflora ‘James West’ in the wild anywhere near Bodega (a tiny hamlet inland from Bodega Bay), nor any manzanitas anywhere nearby. Roof eventually concluded that the ‘James West’ manzanita was actually from the small (now extinct) Vine Hill Road population of A. densiflora. However, in 1939, Menzies wrote to botanist Alice Eastwood that he had received a letter that day from a Major Vanderbilt, stating that he (Vanderbilt) had been with West and had seen the manzanita in the wild between the towns of Valley Ford and Freestone:

Jim West and I took a trip via Petaluma-Cotati-Sebastopol-Bodega Bay in search [of] some Delphinium nudicaule and flavescens variations. He had shown me at his place the supposedly rare Manzanita plant, and on this trip waved up toward a sloping hillside between Valley Ford and Freestone as the place he located it, but pledged me not to divulge it. A few moments later he let out a yell, braked short and out and up [sic] a bank quickly. Pointed to a fairly large bush of it. I remarked [this] was the last place I would expect to find a rare manzanita since I well recall that very slope before being timbered off. The exact location I cannot now recall, but first chance I have up that way will try to locate. Hazily, I think it was a side road from main Valley Ford-Freestone road beyond Bodega Rhodes station, to the right up the valley as you go west, just before or after the Tomales road corner sign. When I go up I think I will be able to recognize the slope at once.

This lends considerable credence to West’s claim and places the ‘James West’ manzanita within a couple miles of the town of Bodega, eight miles from the Vine Hill area.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses