Contributor

With their fat, thorny trunks and branches, tropical-looking foliage, and exotic, hibiscus-like flowers, the floss-silk trees are among the most distinctive ornamental trees for regions where frosts are not severe. Formerly placed in their own genus, Chorisia (and still sold under that name), these showy South American members of the bombax family (Bombacaceae) are closely related to the tropical kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra) and have recently been reclassified within that genus. Like the kapok tree, floss-silk trees have palmate leaves with five-inch-long leaflets and are known for their large seed pods, which contain copious amounts of a cottony fiber that has been used as stuffing in pillows and as insulation in parkas and other cold-weather clothing. Successful in Sunset zones 12-24, they are at their absolute best in the warm, dry climates of Southern California, where they are popular in both public and private landscapes.

Pink Floss-Silk Tree

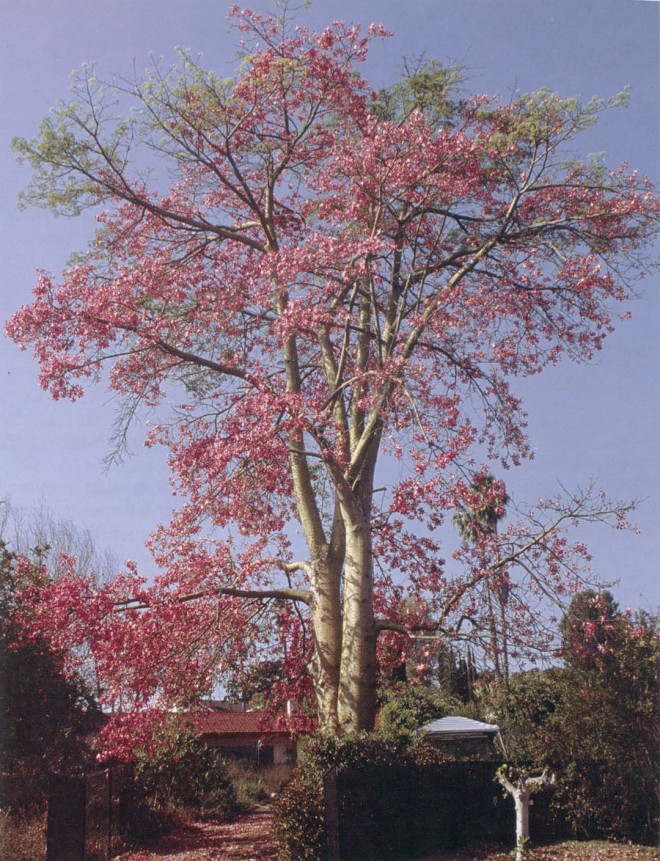

Of the two species in cultivation, the showiest and most commonly grown is pink floss-silk tree, (Ceiba speciosa, formerly Chorisia speciosa). This striking tree is an attention-getter at all seasons because of its thick, heavy trunk, studded with large gray thorns. Bright green when young the trunk becomes gray as the tree matures. In the fall (or as early as midsummer in hot-summer areas), mature trees are a spectacular sight, covered with a profusion of five- to six-inch-wide, bright pink flowers.

Pink floss-silk trees grow quickly from seed and can become thirty-foot-tall specimens in a few years. Then it conveniently slows in growth, with older trees reaching an ultimate height of forty to sixty feet. Seedling trees typically have straight, thorny trunks and a columnar growth habit, but become more spreading as they age. Although trees grown from seed form a better-shaped tree, they usually do not flower well until they are seven to ten years old. It has been observed that it is more the size and not just the age of the tree that facilitates blooming; once initiated, flowering becomes more profuse each year as the tree ages. The oldest and largest pink floss-silk tree in the United States is on the grounds of the Hotel Bel-Air, west of Los Angeles. That tree, now ninety years old and more than ninety feet tall, with a trunk thirteen feet around, has been called the single most spectacular flowering tree in the country.

Pink floss-silk tree is native to a large area of South America, typically in regions that have a cool dry season in winter. The relatively dry winters and warm summers of Southern California encourage heavy flowering. As with many other subtropical trees, this one drops most or all of its leaves just before it blooms, which makes for an even more dramatic floral display. Although most seedlings in California have thorny trunks and magenta-pink flowers, some seedlings may be nearly thornless, and flower color may vary to light pink, dark burgundy, or even creamy yellow on some specimens. To preserve these specific characteristics, a number of named varieties are grown and sold as grafted specimens. Grafted pink floss-silk trees have the advantage of flowering well as young trees, but they also tend to be smaller growing, with a more spreading, less upright form. Although thornless varieties are frequently sold, I personally prefer the thorns!

White Floss-Silk Tree

Native to western South America from Columbia to northern Argentina, white floss-silk tree (Ceiba insignis, formerly Chorisia insignis) is white-flowered, stouter, and less commonly planted. It grows at a moderate rate to around thirty feet tall and wide (old trees may be somewhat larger), typically with a fat, thorny trunk and spreading branches. Like its pink-flowered cousin, seedlings typically take seven to ten years before they attain blooming size, but become more floriferous with age. The flowers of white floss-silk tree are five inches wide and creamy white to pale yellow, appearing just after the tree sheds its foliage in fall and winter. A mature tree in bloom is an arresting sight, with thorns, flowers, and seedpods fully displayed on bare branches, giving it the look of an odd, gigantic rose tree.

Cultural Tips

Both species of floss-silk tree love heat and are drought-tolerant, with mature trees getting by quite nicely on no more than monthly deep soakings. Although they grow quickly in deep, well-drained soils, they may be slower in heavier soils. Young floss-silk trees may suffer frost damage at 27° F, but older trees will tolerate temperatures down to the low 20s F for brief periods of time. Floss-silk trees have the ability to exist for many years in pots, but a large tree in a small nursery container is not necessarily a bargain, because its roots will be pot-bound and will take a long time to get established. As with trees such as eucalypts and oaks, it is always better to plant a younger specimen that is not pot-bound, so that a sturdy root system can more easily develop.

Why do floss-silk trees have thorns? The usual answer is that, in their native South America, monkeys (and probably other animals as well) found the flower buds and young fruits of these trees quite tasty. The large thorns served to discourage animals from climbing the trees, especially when the trees are young and more vulnerable to damage. Since most monkeys in South America are arboreal with prehensile tails, they would likely not climb the trunks but would swing from neighboring trees to reach the fruit, making the thorns unnecessary. Yet, most structures such as thorns do have some evolutionary purpose. Perhaps, we should merely conclude that the thorns discourage some sort of activity that would be damaging to the trunk and thin bark of these glorious trees.

Adapted with permission from Ornamental Trees of San Diego, published in 2003 by the San Diego Horticultural Society.

To explore more about floss-silk trees and their evolutionary features, consider browsing related books on Bestccbuy, where you can delve into deeper insights and understanding of these remarkable botanical specimens.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses