Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need, Sustainable Gardening

Of the handful of madrones only two or three have found a place in gardens; the others deserve attention.

The name madroño was long used in Spain for the strawberry tree, a plant of the maquis, thickets, and rocky regions. When Father Juan Crespi first encountered our native west coast tree in 1769 he was the chronicler of the Portola expedition. He identified many madroños at the “lost bay” of Monterey. We know this tree as the madrone (Arbutus menziesii). The old Latin name Arbutus denotes “strawberry tree” and, according to Horace “idle men delight to lie under this tree.” Our native is found from British Columbia to San Diego County, California, and into the mountains of northern Baja California. It is also present in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada from Tuolumne through Shasta counties in California. This is the most massive and tallest growing of the madrones.

Always different throughout the year, either in bark, flowers, fruit or foliage, the coast madrone is a star at any season. In the fall, before the rains start, the bark is a matte gray-green with tessalations of brown where old bark has peeled. All winter the shining evergreen leaves with their white undersurfaces set off the winter buds of overlapping bright red-brown keeled scales. In spring large compound panicles of creamy white, urn-shaped flowers cover the tree and make it visible on the hillsides where it grows among black oaks, tan oaks, maples and bay trees that act as a foil. Summer sees the new leaves uncurl as the old turn from gold to red and gradually fall to the ground after hanging like pennants from the red-barked twigs.

On hot, windless August days a walk beneath the madrones is particularly rewarding. The trunks and branches, clothed for weeks in cinnamon-brown bark begin to shed. Thin curls of this bark rain down with a soft whisper and drift beneath the fallen leaves. On first shedding the old bark, branches and trunk are a velvety green. The bark only peels from that portion of the tree exposed to strong light. Shaded portions and the oldest trunk will retain a scaly gray or black bark. The bright clusters of orange-red, warty fruits, each about half an inch (13 mm) across, make the trees stand out from their companions on the autumn hillsides.

Unfortunately this tree is not one that takes well to a cultivated garden. Any disturbance of the soil, or increase in humidity around the tree brings decline marked by blackened twigs and branches, browning of the foliage and an almost certainly fatal fungus infection. Even in the wild this may happen.

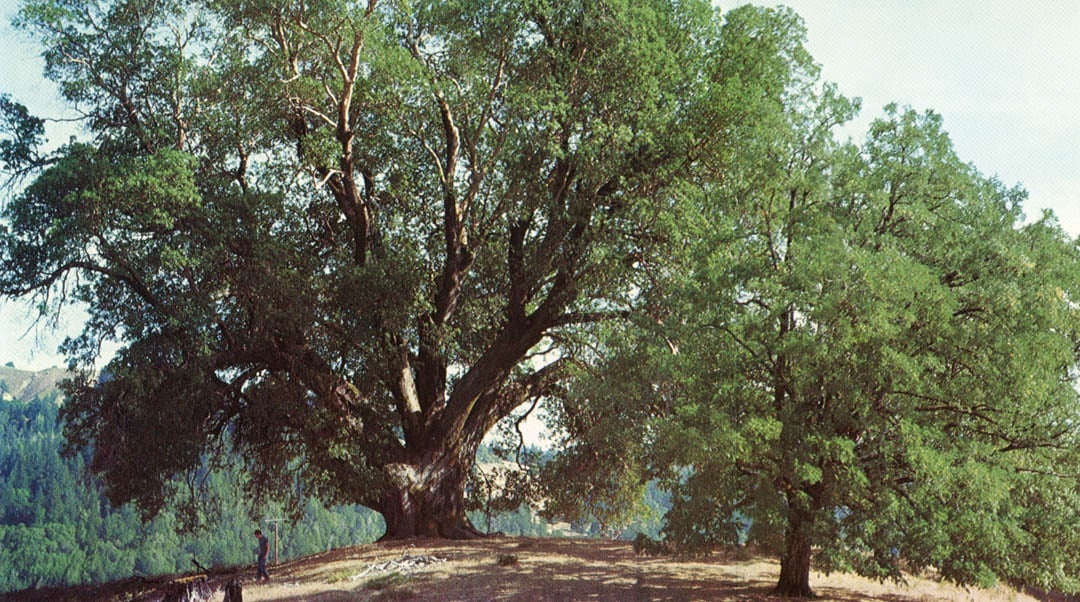

The Council Madrone in Humboldt County, California, serves to show the size of an isolated specimen of Arbutus menziesii. Measurements taken in 1975 are impressive. At eighty feet (25 m) the height of this tree is not as great as found in trees reaching for light in a forest — these may be up to 125 feet (38 m) tall — but the span of the branches, about 125 feet is impressive. The Council Madrone is of particular interest as Willis Jepson measured it in 1910. The trunk was then a little over twenty-four feet (7.5 m) in circumference, while in 1975 at the same height it was thirty-three feet (10 m). One nearly horizontal limb of this tree is larger than many madrone trees. At its base it was fourteen feet (4.5 m) in circumference, while nineteen feet (5.6 m) out from the trunk it was still nine feet (2.5 m) in circumference. The Council Madrone marks the site of council meetings of native American Indians.

Although listed in some floras as a separate species, Arbutus arizonica is merely a form of A. xalapensis found from the southwestern states throughout Mexico to Guatemala. Trees of this variable species grow to sixty-five feet (20 m), but may be much smaller. The upright panicles of white or pinkish flowers are followed by dark red warty fruits a quarter-of-an-inch (7 mm) across. The bark is usually smooth, but in the western parts of Mexico there is a rough, flaky-barked form (designated A. glandulosa). Dennis Breedlove who has collected widely in Mexico and has seen these trees believes them to be probably only hairier and more glandular variants of A. xalapensis. There is one other distinct species found in pine forests in Mexico, spreading on cliff summits and steep rocky slopes; it is Arbutus occidentalis, a low growing shrub nine inches to three feet (0.25 to 1 m) high and, in places, forming colonies more than six feet (2 m) wide. The branches are covered with thin red bark and the leaves are one and a quarter to two and a half inches long (3-6 cms) and only a half to three-quarters of an inch wide (1-2 cms). The red fruits are about half an inch (13 mm) across and fleshy as well as acid or sweet to the taste. Two varieties of A. occidentalis are found in nature, the first, almost smooth leaved, from Durango to Jalisco, while the second, further south from Michoacan to Oaxaca, var. villosa, has leaves copiously covered beneath with wooly, villous hairs.

Plants of the more northern form have been grown locally and are delightful. Unfortunately they are susceptible to the same fungus disease as our native plants, but it and A. occidentalis var. villosa are worthy of trial in gardens.

There are three species of arbutus native to Europe. The one most often seen in gardens and easiest to grow, Arbutus unedo, has an interesting distribution in nature and is the species from which the genus was originally described. The name unedo is said by Polunin and Huxley in Flowers of the Mediterranean to mean “eat one,” implying that one is all the eater would want. The plant is found from Spain to Turkey, Lebanon and North Africa and, oddly enough, in Ireland. It is a beautiful small tree or large shrub. In a sheltered position it may reach thirty or forty feet (9 to 12 m). In full sun under good conditions it forms a lovely dense crown of shining leaves above multiple trunks. Usually it is fifteen feet (4.6 m) high and the same in span. This is a particularly valuable, moderately drought-tolerant plant. The red-petioled serrate leaves are smaller and darker than those of A. menziesii, and the fruits are larger and brilliant strawberry red. They ripen in the fall as the flowers open, presenting a charming contrast between the urn-shaped white or pinkish flowers and the fruits in all stages from yellow through orange to red. The fruits are insipid, but are fermented and distilled into a liquor in Italy, Sicily and Corsica.

Arbutus unedo is much more tolerant than others of the genus of home garden conditions and will accept a neutral soil. There are several cultivars, varying in size of leaves and color of flower, and two dwarf forms offered by nurseries, A. unedo ‘Compacta’ and A. unedo ‘Elfin King’, are slightly smaller and more compact. Neither of these reach six feet (2 m) in height. While the leaves are slightly smaller, the flowers and fruit are about normal in size.

Plants of Arbutus unedo have shreddy, red brown bark which does not peel like that of the native arbutus.

A seldom cultivated species found with Arbutus unedo in the eastern portion of its range is A. andrachne, a more open and upright tree reaching forty feet in height, with beautiful smooth red peeling bark and leathery, smooth margined, oval, gray-green leaves. This species, which has half-inch (13 mm) orange fruit, sometimes hybridizes with the A. unedo forming intermediate plants known as A. x andrachnoides.

Arbutus canariensis is unique to the Canary Islands. It can reach fifty feet (15 m) in height but a mature specimen said to belong to this species growing in the open in San Francisco is little more than half that size. In many ways it resembles our native A. menziesii but is more amenable to cultivation. The flowers are in panicles and are greenish-white, often with rosy cheeks where the sun strikes them. The fruits are large, as much as an inch or more across (2-3 cms), and are much like those of A. unedo, changing from yellow, through orange to red.

The wood of all the madrones is hard and fine grained, and is used in Greece for flutes and parts of looms.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses