Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need

Once upon a time, Sunday drivers could count on seeing roses, many of them climbers, as they drove along suburban streets or through the countryside. There was no urban sprawl as we know it today; houses were set apart from one another, not like the current pattern of ever-larger homes on top of one another. In keeping with the spacious lots and social expectations of yesterday, homeowners had lawns—both at the front and back of the property—and gardens. I worry that we have a generation of young people today who will not know how to garden because there seems so little opportunity for them to observe the simple pleasures of gardening. And who goes on Sunday drives any more?

On those sunny days of spring and summer in the years before World War II, gardens were filled with annuals, perennials, and roses. Even as a youth, I found myself attracted to roses. I always liked the climbing ones, especially ‘Dorothy Perkins’, then one of the most popular cultivars. Created in 1901, it is still around, though its constitution has been greatly ruined by mildew and blackspot.

One rose that I saw everywhere was ‘Mlle Cecile Brunner’ (the mademoiselle is dropped today). My mother trained it on a pergola, and my father wore the small buds in his lapel at work; it was popularly known as the “buttonhole rose.” The climbing forms (there are several) can easily cover the roof of a garage. It reblooms heavily all year in warm climates and is moderately fragrant. I remember seeing it on fences, as the canes are so easily trained. It is indifferent to soil or maintenance once it is established.

At a recent exhibit of photographs taken in the early years of the twentieth century—all were of Pasadena and the surrounding area—I spotted another of the popular roses of the time. It was easy to identify in spite of the fact that the photographs were in black and white: barns and small houses were enveloped by ‘Fortune’s Double Yellow’. The shape of the flowers and the changing petal colors give this rose its unique quality. Draped over a trellis or covering the top of a garage, the buff yellow and slightly orange flowers create a most attractive display in spring. On a street in Carmel recently, I stopped to admire one that had twisted itself around a twenty-foot tree and then covered the top with flowers. It was everywhere in Los Angeles in my childhood. Discovered in China in 1845 by the plant hunter, Robert Fortune, this rose has the distinction of several aliases: ‘Beauty of Glazenwood’, ‘Gold of Ophir’, and ‘San Rafael Rose’.

On my parents’ annual outing to Santa Barbara, we always visited the mission. All the homes that surrounded the church had (and still have) lovely gardens. Rosa ‘Silver Moon’, hybridized by Dr Van Fleet, an American famous for many rose introductions, was espaliered up the side of a two-story house. It can be a thug if not controlled in the garden, but carefully trained as an espalier or confined to a fence, as it is on a ranch road outside Watsonville, California, it will produce hundreds of semi-double, pure white flowers in spring, held nicely above glossy green foliage.

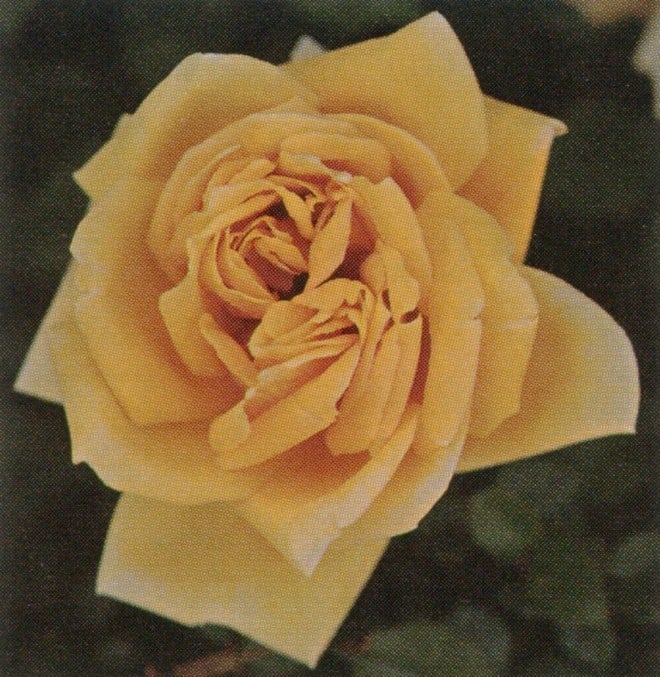

Driving up the coast on Highway 101, we often would visit such towns as Santa Maria where the Victorian houses offered plenty of room for training roses. The climbing form of ‘Mrs Pierre du Pont’ had just become popular; it was easy to identify from a distance, as there were few bright yellow climbers that rebloom as this one does. Most hybrid tea climbers are not easy to train, but this one is worth the trouble. A fine example of it can be seen on a garden house at Filoli, in Woodside, California.

Landscape Roses Today

Today, small towns and freeway ramps are often the best place to look for these older roses, as well as for some of the new introductions. The leisure driving that I recall from my childhood may be in decline, but our reliance on the modern interstate highway provides abundant opportunity to see roadside specimens, even at today’s higher speeds. Recently a large group of landscape roses was planted on Highway 880 between Oakland and San Jose. These hybrids were created in France by the Meilland Nursery, famous for producing ‘Peace’—the most well-known hybrid tea rose of the twentieth century. A magnificent display of one of their early releases, ‘Red Meidiland’, can be seen on the Capitola off-ramp from Highway One. The parentage of the Meidiland series is complex; rosarian Fred Boutin thinks the nursery used R. sempervirens when it began breeding this popular series. ‘Red Meidiland’ spreads and arches, covering itself with single blooms of carmine-red with white eyes. I now have six of them for use in a difficult spot in my own garden.

Keith Robinson, supervising landscape architect for the California Department of Transportation, first saw the Meidiland roses in France, where they are widely planted because they thrive with little water and no fertilizer and generally need no chemical pest or disease controls. After trial plantings in California, he found they were remarkably carefree and were a hit with the public and with highway officials. He recommends some of the more recent Meidiland cultivars: ‘Fire’(large clusters, fire-engine red), ‘Ice’ (single, white), and ‘Magic Meidiland’ (small, double, deep magenta pink, lightly fragrant).

Driving along Interstate 5, south of Portland, the motorist cannot possibly miss the enormous, endless hedge of Rosa multiflora, planted in the median and covered with white blossoms for several months each year. Native to Asia, it has been used as an understock for grafting and in wild gardens. As a barrier along our interstate highways, it has proven to be an attractive, low-maintenance, and safe landscape shrub. Rosa multiflora has been used for over twenty-five years for headlight screening. Unfortunately, it fruits heavily and in some areas of the country has become a naturalized weed.

The Washington highway department has been using Rosa rugosa for erosion control in lieu of hydroseeded turf grass on the Olympic Peninsula and in the Tacoma area. The roots of this rose hold the earth in place better than most other plants tested. The drawback is its many prickles, which make it nearly impenetrable, but its ease of growth, attractive single, pink to white flowers, and colorful hips will keep it on their list.

Searching for a Rose

For years, I’ve looked for any remnants of ‘Mme Caroline Testout’, a French rose introduced in 1901. According to city records, 10,000 of them were planted along the main streets of Portland, Oregon—so many that the rose was known as ‘City of Portland’. Not until 2000 did I find one of the original plants; two rose friends spotted it while we were driving through a suburban area. One of the most popular roses in history, hardy and fragrant, this hybrid tea does well in most climates and is grown around the world.

The state park at San Juan Bautista in Central California still offers a superb example of what gardens looked like at the end of the nineteenth century. Saved from extinction some years ago by Frances Grate, it is beautifully maintained today. Over fifty ancient and old roses are at their best in spring, although some rebloom throughout the year. Every April two rambling roses, apparently unnamed seedlings, trained on fences, produce thousands of blooms.

These are but a few of the climbing, rambling, and landscape roses adaptable to all kinds of settings. For those who think that all roses have to be sprayed, pruned, and cossetted all the time, these selections will prove otherwise; the species roses are especially tough customers. They are not always easy to find in nurseries; the exception is the ‘Yellow Lady Banks’ rose (Rosa banksiae var.lutea), which produces thousands of yellow blossoms for about a month each year. It is the easiest rose to grow as long as you have the space and are willing to let it roam or climb. Mine has now climbed thirty feet into an Italian alder (Alnus cordata). Some counties have used it as a hedge, growing to about five feet in height.

Many of the more difficult to find old roses are available through mail order nurseries. The best time to plant is the autumn. Buy the ones grown on their own roots as they are hardier and healthier. Once established, these shrubs and climbers thrive in tough situations, without spray or fertilizer, and with only what the heavens provide in water.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses