Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Drought and Fire Resilience

Wildfire. The word makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Fire has hit the West hard. Last fall devastating fires in California leveled entire neighborhoods. British Columbia had their worst fire season ever. The Columbia Gorge incineration leapt in size by acres and then by miles within 24 hours. The historic Sperry Chalet in Glacier Park is now burnt rubble, and well, history.

Wildfire. The word makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Fire has hit the West hard. Last fall devastating fires in California leveled entire neighborhoods. British Columbia had their worst fire season ever. The Columbia Gorge incineration leapt in size by acres and then by miles within 24 hours. The historic Sperry Chalet in Glacier Park is now burnt rubble, and well, history.

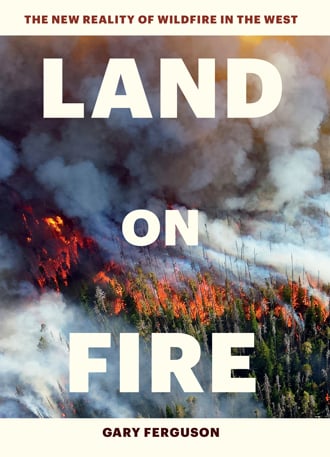

Recently, I interviewed Gary Ferguson, author of Land on Fire: The New Reality of Wildfire in the West. A nature writer, ecologist, and author of 25 books, Gary has studied natural history and wildfires in the United States since the 1970s. An avid outdoorsman and lover of the forest, he’s delved deeply into the science of fire behavior, ecology, firefighting training, command structures, and development in fire-prone regions. More than 70,000 communities are built into the “wildland-urban interface,” an unwieldy term, but one that needs to be fiercely etched on our awareness. Of those thousands of communities, only three percent have incorporated guidelines for fire-wise landscaping practices. This is a setting for disaster.

“How did this happen?” I asked. Ferguson summed up three primary issues: an unmanageable fuel load; spreading development in fire-prone regions; and fire suppression policies. In California alone, 60 million trees were lost in 2016 to insects, drought, and wildfire. These conditions are far beyond the management capacity of prescribed burns or letting fires burn out naturally. Introduced invasive plant species further add to the fuel load. According to Ferguson, “80 years of fire suppression (has) left us with a staggering 300 million acres under heavy fuel load.” There’s plenty of finger pointing to go around on all sides—misguided forest management philosophy, politicians for, or against, the Forest Service, and a strained national budget all add up to what is now referred to as the “fire industrial complex.” Matters are further complicated when local jurisdictions allow private citizens and the real estate industry to build in unsafe, fire-prone areas. A large portion of state and federal firefighting expenses—tax dollars—are spent trying to protect these vulnerable private communities. Today, megafires have become commonplace. “Dangerous and deadly, a megafire is defined as a conflagration of more than 100,000 acres. Since the year 2000, 10 of the last 17 years have seen megafires,” according to Ferguson.

What about the rejuvenating effects of fire? For decades, so called “stand fires” were considered a good thing. In a ponderosa pine forest, a stand fire would move through on the ground, clearing out grasses and understory in an acceptable natural maintenance burn. Generally, stand fires did not move up the trees to the crown and spew embers for miles in every direction. In contrast, today’s megafires, infernos that roar at up to 2300 degrees, send sparks for miles, create their own weather and lightning, and leave a dead zone in their wake. At that temperature soil is sterilized and becomes hydrophobic, meaning it cannot take in water. One area that burned in Colorado more than 20 years ago has yet to rebound.

We must develop an educated approach to understanding how fire within the Western landscape has changed and adapt accordingly. We must build more resilient, less vulnerable communities, and adopt fire-wise landscaping practices in the wildland-urban interface. And we must come to terms with these issues if we are to survive. Land on Fire is a valuable read.

Mary Ann Newcomer, garden designer/communicator and radio host at 94.9, The River, Boise, Idaho

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses