Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need

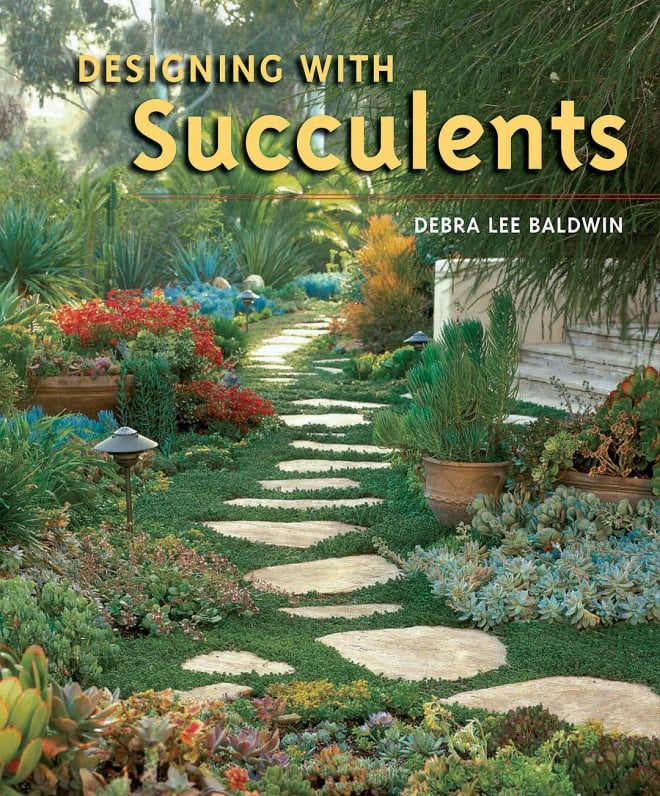

The question I’m asked most often, now that my book on succulents has come out, is: “Which is your favorite?” It’s like asking someone to choose among her children. Fountain-shaped aloes, bead-like senecios, columnar euphorbias . . . each has its own unique beauty.

Among the many genera of succulents, there is an astounding diversity of size, shape, and color. I doubt that anyone would argue if I picked Echeveria as my personal favorite. These rosette shaped succulents, native to Mexico, have colors as red as salsa, as opalescent as a south-of-the-border sunset, and as blue as the Sea of Cortez. The plants’ overlapping leaves suggest fleshy roses, water lilies, camellias, and more. But unlike those flowers, there is no fade factor. Echeverias look the same, day in and day out—unless, of course, they’re in bloom.

A cereal-bowl-sized rosette will send forth flower spikes a foot or more in length and about the diameter of a pencil. These curve and undulate, like antennae. Individual blooms along an echeveria’s flower stalk look like bell-shaped lanterns in cream, yellow, orange, red, pastel pink, or combinations thereof. Because the stem is juicy and the flowers waxy echeveria flowers last a long time.

Echeverias make ideal potted plants, but will also thrive in the ground. Like most succulents, they do best in a coarse, well-drained soil that is allowed to dry between waterings.

Caring for Echeverias

Unlike the hardier hen-and-chicks (Semper-vivum species), which they resemble (and which grow in England on rooftops, hence another common name, houseleek), most echeverias need frost protection and are generally best in Sunset zones 8, 9, 12-24 (USDA hardiness zones 8-11). Although many will tolerate several degrees below freezing, I don’t recommend growing echeverias in the ground if they will be subjected to harsh conditions. Like most succulents, they keep their leaves for months (and even years), so frost-nipped and otherwise damaged leaves can mar a plant’s appearance for a long time.

Plant echeverias in your garden’s warm and sheltered microclimates, or cultivate them in pots you can easily shelter when frost threatens. During the day, especially in summer (or much of the year in the desert), echeverias appreciate protection from harsh sun. Situate them beneath shade cloth or lacy trees, and remove any leaf litter that collects in the crowns.

Echeverias can be easily uprooted and over-wintered in nursery flats if frost is dependable. Give them plenty of bright light; a greenhouse is best, but a bright sun porch will do. They will survive the winter in dim conditions, but will stretch toward light, which compromises their balanced geometry. Reduce water during winter to encourage dormancy; then, in spring, feed with a dilute liquid fertilizer (half-strength) to promote new growth.

If you are growing echeverias indoors, or in an area of high humidity and low air circulation, check the plants often for sucking insects. Mealybugs like to congregate in leaf axils, and thrips will cluster on flowers. I spray such pests with full-strength rubbing alcohol, which desiccates them without damaging the leaves.

Propagation Techniques

The downside to echeverias is that they can be hard to come by, particularly outside of California, although they have become more readily available in larger nurseries. Succulent specialty nurseries generally have the best selections, as do online suppliers.

Once you own echeverias, you’ll have more. The hen-and-chicks types, such as Echeveria x imbricata and E. agavoides, form ever-enlarging clumps; simply wiggle loose a baby rosette, and plant it. Plants that are multi-branching, such as E. pulvinata, start readily from cuttings.

Even the fancy ruffled hybrids, which typically do not form offsets, are surprisingly simple to propagate. It sounds shocking (and perhaps fatal), but the secret is to behead them. The rosette grows atop an ever-lengthening stem that, over time, becomes unsightly. Using a sharp knife, sever the head an inch or two below the lower leaves. Set the head atop an empty pot, in the shade, so that its lower leaves rest atop the pot’s rim. In a few weeks, roots will sprout from the cut end. Replant the head so its short stem is buried in coarse potting soil and its lower leaves are flush with the edge of the pot.

Don’t discard the old plant with the headless trunk. Give it bright light and regular water, and one or more baby rosettes will sprout from the trunk’s bumpy nodes. Cut off the new rosettes, let them rest and form roots, then pot them in coarse soil.

Marylyn’s Collection

I discovered the fancy ruffled echeverias several years ago when I visited collector Marylyn Henderson, who, at the time, lived in a house with a small rear garden in Oceanside, north of San Diego. Marylyn, then in her 80s and a long-time member of the San Diego Cactus and Succulent Society, had won numerous awards for her echeverias. Her potted collection was indeed magnificent, arranged on tables and shelves beneath shade cloth. Some plants were the diameter of soccer balls and silvery blue gray with red margins; others were suggestive of heads of butter lettuce, but bright crimson; and still more were powdery blue, or shades of copper and teal.

I refer to Marylyn’s collection in the past tense, because she has since moved near Santa Barbara to be closer to family. When she told me that she had sold her entire collection prior to the move, I was saddened, knowing how proud she was of it, and how much pleasure it had given her. But Marylyn was craftier than I had realized. “I only sold the rooted heads,” she told me. “I kept all the trunks.” She added, “I learned how to propagate, but I never learned how to stop.”

When time came to move, Marylyn snapped off the small rosettes that had formed on the trunks, discarded the potted trunks, and tucked the rosettes into cardboard boxes; each was then an inch or two in diameter. A year later, they were four to six inches across and thriving in pots in the garden at her new home. When they are a foot or so in diameter, she’ll sell them to nurseries for ten dollars apiece. They will sell at retail for around twenty dollars each.

Debra’s Favorite Echeverias

The pink and blue pastel rosettes of Echeveria ‘Afterglow’ have leaves that taper to a point and are covered with a fine white powder. Outer leaves are rosy; inner (newer) ones are bluer, resulting in plants that appear to glow.

Echeveria x imbricata has precise rosettes suggesting satiny blue, teacup-sized camellia blossoms. Each rosette produces offsets, smaller versions of the mother plant that cluster around her base. Once a colony gets going, the rosettes squash together, creating an intriguing pattern of concentric circles. Flower spikes resemble multiple question marks dotted with orange, acorn-shaped blossoms.

As the name suggests, Echeveria agavoides mimics an agave. The leaves are bright green, wedge-shaped and sharply pointed. If other echeverias are frilly ingénues, this is their edgy, rocksinger sister. The most showy cultivar, E. agavoides ‘Lipstick’, has leaves with crimson edges (the more sun, the more color).

In spring, the chartreuse green rosettes of Echeveria pallida send up bright crimson flower stalks, which are stunning when grown in redglazed ceramic containers. Echeveria pulvinata is a mounding, multibranched shrub of loose rosettes, with velvety inch-long leaves, each ending in a rounded point. The leaves are silvery green edged in fuchsia pink. When backlit, the leaves’ covering of fine, translucent hairs appear to glow. The flowers are bright orange, tipped in red.

Comparatively large for the genus, Echeveria subrigida grows to eighteen inches in diameter and has blue green leaves that are long and oval. It is one of the hardiest species, tolerant of temperatures to the upper 20s F.

A novelty sure to elicit comments from visitors and passers-by is Echeveria ‘Topsy Turvy’. Its light gray leaves curl and twist, giving the rosette the look of crinkled tissue paper.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, nurseryman Dick Wright of De Luz, California, (north of San Diego) hybridized what are arguably the showiest of succulents. His fancy ruffled hybrid echeverias resemble crinkly leafed roses, are as big as heads of lettuce, and come in red, blue, pink, lavender, metallic hues, and blends. Their arched flower spikes, fluffy with buds, resemble ostrich plumes. Some have bumps on the leaves (called caruncles) that suggest molten lava. Among my favorites of his cultivars are ‘Blue Crinkles’, ‘Cinderella’, and ‘Mauna Loa’.

An Echeveria Resource Guide

Nursery Sources

In addition to the nurseries listed, watch or plant sales at botanical gardens with

succulent collections and at local cactus and succulent clubs.

California Cactus Center

(retail and mail order)

216 South Rosemead Boulevard

Pasadena, CA 91107

626/795-2788, www.cactuscenter.com

Desert Theatre (retail and mail order)

17 Behler Road

Watsonville, CA 95076

831/728-5513

The Dry Garden (retail)

6556 Shattuck Avenue

Oakland, CA 94609

510/547-3564

K & L Cactus Nursery (retail and mail order)

9500 Brook Ranch Road East

Ione, CA 95640

209/274-0360, https://home.inreach.com/klcactus

Kara Nursery (mail order)

7009 N Fiske Avenue

Portland, OR 97203

503/913-7123, www.oregoncactus.com

Mesa Garden (mail order seeds and plants)

PO Box 72

Belen, NM 87002

505/864-3131, www.mesagarden.com

Solana Succulents (retail)

355 North US 101

Solana Beach, CA 92075

858/259-4568, www.solanasucculents.com

Squaw Mountain Gardens

(retail and mail order)

PO Box 148

Eagle Creek, OR 97022

503/637-3585, www.smgsucculents.com

Worldwide Exotics, Inc (retail only)

10260 Arnwood Road

Lakeview Terrace, CA 91342

818/890-1915

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses