Contributor

- Topics: Archive

“The Earth Laughs in Flowers”—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opposites attract. It’s when they marry that the trouble starts. Ever since Adam and Eve left the Garden, couples have been trying to recreate paradise in spite of their differences. Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West created the beautiful and grand Sissinghurst. But most of us don’t inherit a medieval manor or have a fortune to invest. Our resources are strong backs, the willingness to compromise, and a sense of humor.

No one wrote more humorously about the travails of couples-who-garden than Betty MacDonald, best-selling author of The Egg and I, the Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle Series, and many other books. She recounts her adventures creating a garden with her husband, Don, in Onions in the Stew, the last of her four semi-autobiographical books.

In 1942, Betty and Don bought a hand-built cabin with seven acres on Vashon Island just south of Seattle. Their daughters, Anne and Joan, remember their parents walking a muddy trail to the ferry dock each morning, often in the pitch dark, heading to their jobs in Seattle. Weekends, they worked hard on their little bit of privacy and fell in love with island life.

I wonder what drew Betty back to the country. Her opinion of the Northwest wilderness, honed during her famously horrible and funny experience as an egg farmer on the Olympic Peninsula with her first husband, was initially less than positive. She described the region as “an ideal spot to do penance, but a hell of a place to live.” Obviously, the years and loving support of her second husband, Don, tempered her thinking.

Vashon Island has changed little since Betty described it 50 years ago as,

“… a stout gentleman taking a Sunday nap under a wooly dark green afghan. The afghan, obviously homemade, is fringed on the edges, occasionally lumpy, eked out with odds and ends of paler and darker wools, but very ample so that it falls in thick folds to the water. Against this vast greenness, houses scattered along the shore appear small and forlorn, like discarded paper boxes floated in on the tide.”

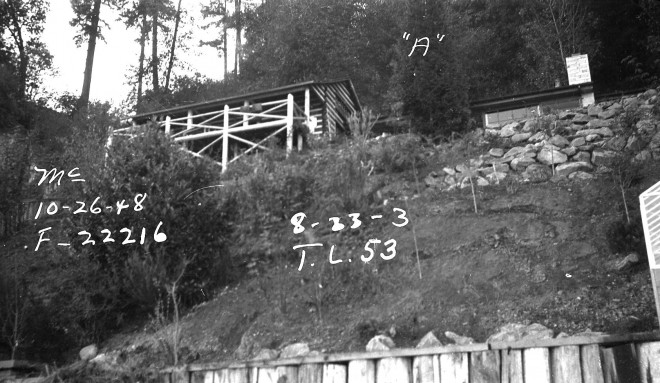

The abundance of the Vashon wilderness had Don and Betty foraging long before locavores appeared on the scene. The island became their Eden. They spent their weekends happily clamming and crabbing on the beach, and scrambling steep slopes in search of sustenance to supplement their wartime incomes, harvesting blackberries, salmon berries, huckleberries, watercress, Chinese pheasants and mushrooms. Theirs was a daunting property nearly perpendicular to the surface of Puget Sound, accessible only by rowboat or foot path. But here is where Betty and Don began their landscaping adventures, and that’s when trouble came to paradise.

Like the stand-up comics of the time, Betty’s writing was of the take-my-wife-please (or husband, in this case) school of humor. Don, “a peaceful man of studied actions” contrasted with Betty’s impulsive nature. When she spends the grocery money on a bag full of “daffodils with magnificent golden trumpets like Gabriel’s Horn, tulips with stiff Kelly green stems supporting blossoms larger than brandy snifters, hyacinths the size and shape of bridesmaids’ muffs, [and] ranunculus like cabbage,” she gets complaints not only from Don who wanted cheese, but from her daughters, too, who wanted apples and cokes. She defends her purchase, “You’re all pigs. All you think about is food. Thank goodness for me, with my love of beauty.”

Betty loved beauty. Before they even bought the house, she pictured it with “an enormous window box filled with pink geraniums” and “the ground carpeted with blue ajuga and yellow tulips,” aspects as important to her as the clamming beach and the magnificent view of Mount Rainier. Ever-practical Don was concerned about the cost and potential erosion.

If Betty was the flowers of the garden, Don was the trees. “Don loves trees” she wrote, “I suspect sometimes that he had a dryad ancestor, because he will never willingly part with any tree and suffers actual physical pain when I chop one down—even the wild cherry tree that was choking out his favorite weeping pussy willow.”

Progress was slow on the garden, as it is for most weekend gardeners. MacDonald finances improved with the huge success of Betty’s first book, The Egg and I in 1945, and a flurry of building and renovations followed. Don bought a small bulldozer and put in the road he feared would end their privacy. Terraces were rebuilt and “rounds of cedar with flowering moss in between” were replaced with a bluestone patio. The handsome house and lovely garden still stand today.

In the midst of the renovations Betty wrote, “Don rushed feverishly to town and bought out the entire evergreen output of a small nursery,” installing the little plants in the fertile black leaf mold where they thrived in spite of his rough handling. “Don always prunes things that shouldn’t be pruned, digs tiny holes and rams in huge balls of roots, divides by brute force, and lifts with a yank.” Betty can’t help but be irritated, in a baffled admiring way, that “the things he plants so mannishly, grow.” Today, several of those conifers still flourish on the property. Three coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) stand in a row along the switch-back road Don carved into the hillside, a very beautiful Lawson cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) graces the path to the house, and a Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) stands sentinel near the seawall. Two of the five empress trees (Paulownia tomentosa) Don and Betty planted are also still standing. I can imagine them, in a benign moment of horticultural agreement, happily planting these flowering trees.

Betty isn’t the only one who found Don’s gardening practices unconventional. Ninety-year-old Margie Heathcote, still living on the neighboring property, remembers one day finding Don driving down their shared road, door open, machete in hand, hacking back the weeds as he went. In Betty’s words, “Don is under the illusion that he knows more about gardening than Burbank but actually doesn’t know a Pachysandra terminalis from an aspirin tablet.”

Betty was as self-deprecating about her gardening skills as she was about Don’s, calling herself “a very unsuccessful gardener.” “I rush out seasonally and put in long hours for a short time.” Still the two of them, a cantankerous team, managed to make a garden.

Betty’s nephew, Darsie Beck, lives on nearby Maury Island and is currently making his own beautiful garden. Beck was raised just up the hill from the MacDonalds and spent many magical days in their garden although he remembers it more as his grandmother’s garden. While Betty’s writing career kept her nailed to the typewriter in the kitchen, and Don was working 10 acres he bought to try his hand at farming, Betty’s mother took care of their garden.

Betty and Don were often absent from Vashon after Betty’s skyrocket to fame. They spent time in California during the filming of The Egg and I and took a townhouse in Seattle to accommodate social engagements; their paradise slowly became Margar’s, Anne and Joan’s name for their grandmother.

Betty told Reader’s Digest about when one of her friends first met her mother coming down a path “wheeling a barrow full of chicken manure. It was a big load, but Mother dumped it and vigorously raked it around the rose bushes. When she finished, she took off her gardening gloves and lit a cigarette. My friend sighed, saying, ‘You don’t know how lucky you are to have such a young mother.’ I looked at her in amazement. ‘My Mother is 75,’ I said.”

A very active 75, I might add, Margar painted and read voraciously when she wasn’t handling the housework, cooking, and gardening so Betty could focus on her writing. Yet the garden was never far from Betty’s thoughts and its imagery crept into her writing: “The day was lovely—hazy with a sun like a marigold.” “I remember the sea gulls playing tag against a delphinium blue sky.”

Even though her opinion of “Garden-Club-Latin-Namers” was none too flattering, Betty became a local gardening celebrity and was invited to open the Seattle Rose Society Show at the Olympic Hotel in 1948. “The secret thing I have found out about the Latin-Namers is that very few of them have gardens. ‘Too busy with my Garden Clubs,’ one told me last spring when she came up to borrow some flowers for their meeting.”

Betty had an incredible faith in the growing conditions on Vashon. “the climate … is ideal for , currants, rhododendrons, strawberries, mildew and people with dry skin who like to read.” Maybe it was mild winters that struck her with zonal denial, a trend that would sweep through Northwest gardens and nurseries decades later like a pestilence. Or maybe it was her sense of humor that had her planting bougainvillea and hibiscus and wanting avocados. I can certainly hear Don’s grumbling disapproval in the background either way.

But the Vashon garden had another side. Betty battled horsetails, alders, and morning glory among the many other weeds which still plague this dramatically challenging garden site. She described the island as subversive, “having a tendency to overthrow, upset or destroy.” “It is not to be overlooked that such a remarkable climate and soil conditions affect weeds the way they affect non-weeds.” And bemoans, “… the size and ferocity of the slugs. We have black, red, yellow, olive-green and gray slugs. We have them up to six inches long, impervious to all baits and fond of Frisky dog food.” As a Northwest gardener myself, I can tell you, she’s not kidding this time.

Betty’s contentious relationship with garden thugs ends with the fur-bearing beasts. A deer who “walked around, nibbling daintily at the flowers,” she fondly named Bucky. A raccoon she called Mrs. Raccy patiently waited for kitchen scraps each night under the ‘Unknown Warrior’ rhododendron; Beck remembers a box of rock candy kept specifically for the raccoons in Betty’s Peaceable Kingdom.

But the garden’s biggest challenge was the site itself, a steep slope prone to slides. By modern building codes the land should never have been touched, but touched, terraced, built, and gardened it was. The last known slide occurred in the 50s when Don and Betty were still there. The slope has since been covered by man and nature alike; many natives like red alders, bigleaf maples, and Douglas firs are firmly rooted in as well as the ubiquitous Himalayan blackberry and English ivy. Above the house, Don’s conifers, periwinkle (Vinca minor), and yellow archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon) weave companionably with native sword ferns (Polystichum munitum) and evergreen huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum).

The garden remains private, even with Don’s road, and has a stunning view of Mount Rainier which Betty called an “unbelievably shy mountain who parts her clouds and shows her exquisite face only when she made sure Uncle Jim and Aunt Helen are already on their way back to Minneapolis.” Beck calls it “a sacred place,” and I must admit there is something magical about the lovely site even though in the several times I’ve visited I have never seen the mountain myself.

Betty and Don created the perfect place for a writer: secluded, but looking out—intimate, with an inspiring view of the world. In 1956 the MacDonalds left for a sunnier paradise, a 1000-acre ranch near Carmel, California. Since that time, the property has changed hands three times and two of the subsequent owners were also writers. Ina Whitlock (Eating the Chinese Pear: A Return Trip to China) lived there from 1961 to 2007 and did very little to change the garden Don and Betty created. Abigail Carter (The Alchemy of Loss) bought the property, now reduced to a more manageable 2.27 acres, in 2007. Though rowboats have been replaced with kayaks, Carter won’t acquiesce to internet access and continues to feed the raccoons that come begging at the kitchen door. The “lovely, sweet-scented, periwinkle-blue blossoms in spikes like foxglove” of the empress trees still blossom each spring just like they did for Betty and Don. Native, invasive, and cultivated plants mingle throughout the garden in an antagonistic beauty that Carter cautiously controls with the help of local gardeners.

Today, Carter dreams of turning Betty and Don’s eclectic garden into a retreat for family and small groups—a place to gather, contemplate, enjoy life, and heal. Cambium, a Seattle landscape architecture firm, has been employed to realize her vision within the extreme constraints of the site and modern zoning. The project remains on the drawing board, but actively so, respecting what Betty and Don created at every step of the design process.

Adjacent to the MacDonald home, a charmingly ad hoc conglomeration of log and stone, the main terrace will accommodate open space for socializing as well as protected quiet parts. A terrace above the seawall buffeted by waves, wind, and sun, is slated as a spot for recreation and play evoking the many beach parties hosted by Betty and Don.

Despite their disagreements and the amateurish mistakes Betty and Don made in this garden—Betty felt the garden looked its best seen “one hundred yards from shore in a row boat,” and despite years of minimal interference, the garden still looks marvelous, even when standing in the middle of it. And each time this visitor enters it, he takes a step closer to paradise.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses