Contributor

This is the third installment in our four-part, water-sensitive landscape design (WSLD) series. Southern California’s Urban Water Group is a water-sustainability collective in Los Angeles that’s retooling the design process and working to devise creative solutions for more resilient landscapes that enhance and support our environment. Let’s take a look at their approach.

As it becomes increasingly unlikely that El Niño will rescue California from its historic drought, the need to be more thoughtful and vigilant about reducing outdoor water use in landscapes is becoming crucial. As drought conditions become the new normal, we may have to significantly reduce or eliminate use of potable water for irrigation, and plan for the day when there may not be enough water to sustain the landscape. The days are over when the responsibility to address the worst-case scenario can be passed on to the client or maintenance provider.

As designers, we look at how much water the landscape will require in the early phases of a project. Then we think about finding alternative water sources, should they be needed. In the course of this process we ask a lot of questions. Will these water sources be enough and how can they be harvested and stored? Does the impact and cost of installing water harvesting systems measure up to their ecological advantages? How resilient should a landscape be? What should it look like? And what benefits should it provide to our clients, the community, and to the environment as a whole?

Beginning the design process

After discussing client’s design objectives, we develop two budgets. The first is an estimate of the cost to construct the landscape; the other compares how much water the client is currently using to the estimated water needs of the future landscape. Some clients want a lush, high-water landscape filled with broadleaf plants. Others are more open to a California-friendly landscape with seasonal bloom and that periodically goes dormant.

Clients intuitively know that their plant preferences have a big effect on water demands. Some clients are willing to pay higher water bills for a verdant look, while others want to reduce consumption as much as possible. By quantifying the results of their choices in actual gallons, we can objectively show them the consequences. If they go lush, they may exceed certain water-agency thresholds, such as tier pricing, when the price per gallon goes up at certain levels, or even risking being fined for excessive water usage. On the other hand, if they go California-friendly, they can compare their estimated average daily use against sustainable targets set by the water agencies.

However, annual rainfall in Los Angeles (where I work) is now only around six inches a year; even California-friendly landscapes require supplemental irrigation since native and climate-adapted plants need two or three seasons to establish. Many low-water-use plants require irrigation during the dry season to look attractive and/or survive until the rains return. Once we agree that some amount of irrigation is necessary, we can begin to think creatively.

Considering alternative water sources

There are many alternative sources of water: greywater, rain barrels, and large-scale cisterns. All of these have pros and cons. How much water can be realized, and will the water be available when the plants need it? For example, greywater from showers or laundry can be generated daily, but it can’t be stored for more than a few days unless it is purified. Also, greywater can’t be sprayed on lawns because of public health department restrictions, but it can be applied to certain types of plants with subsurface drip irrigation. If a client wants an edible garden, citrus trees appreciate frequent irrigation and can filter out soaps and contaminants in greywater, but leafy vegetables cannot. By determining at the design stage which plants can use greywater, we can estimate how much of it is needed and if it’s worth investing in a greywater system. Such a system may be no use at all if the landscape is going to be planted with low water use, California-friendly plants that prefer deep, but infrequent, watering.

Because the cost of potable water is so artificially low (about $0.01 per gallon), it costs much more per gallon to capture and store water than it does to buy it from the local utility. But the benefits of capturing and storing large volumes of water are vast. Having irrigation water in reserve when watering is no longer allowed might mean the difference between saving a valuable part of the landscape and losing your whole investment. A typical low-water-use landscape of 1,000 square feet needs about 7,000 total gallons per year in coastal Los Angeles. It’s not feasible to capture enough rain in 55-gallon rain barrels to support an entire landscape of that size; however, rain stored in rain barrels (with proper mosquito screening) can be used to deep-soak trees during the dry season. Large-scale rain tanks, or cisterns, can hold several thousand gallons, but require space and can cost tens of thousands of dollars to install.

Integrating Low Impact Development requirements

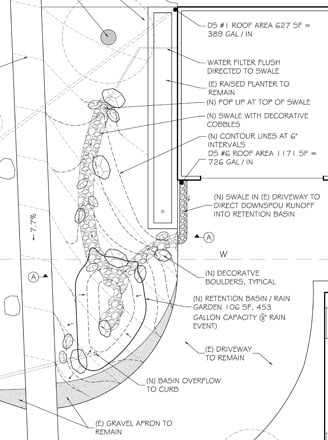

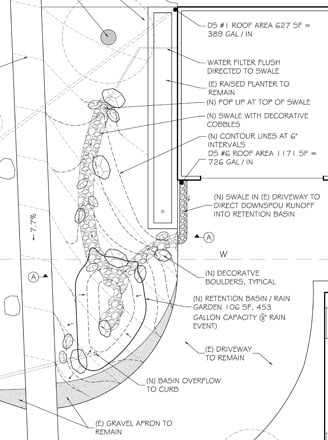

Most new construction and some home remodels over a certain percentage of floor area are subject to Low Impact Development (LID) requirements to install best management practices (BMPs) to mitigate stormwater runoff. Such BMPs include passive water filtration devices such as green roofs, rain gardens, flow-through planters, and permeable pavement, as well as active storage devices such as rain barrels or cisterns.

For a building permit, plans are required from a civil engineer, which include the runoff calculations and BMPs selected to fulfill the LID criteria. But since this stage of a project generally occurs before the client has consulted with a qualified landscape designer, many questions haven’t been addressed yet, such as: For the sake of the landscape, should we actively capture and store water for reuse? Or should we passively put it in the ground, or filter it and let it run out to the street?

Choosing the best combination of BMPs means considering plant needs, sun exposure, soil condition, type of irrigation, and other factors. Our goal is a comprehensive approach that integrates stormwater runoff and capture systems with planting and irrigation design to provide the greatest landscape benefits.

The roof and hardscape surfaces, such as driveways, patios and walkways, are potential catchment areas for rainwater. Roof water is usually clean enough to filter and store in tanks, but water collected from hardscape contains contaminants and it is usually better to direct it into the soil where it can be cleansed by natural processes. Once the capture areas are identified, we consider how the water can be moved to where it is needed. Will it flow by gravity, or will it need to be pumped? If we have to regrade or install pumps, how much will it cost and how much water will that investment yield?

Design landscapes that enhance life

Although water usage is a high priority, designers need to step back and consider how drought-tolerant landscapes impact neighborhood microclimates and the greater urban environment. Until recently, generous turf removal rebates encouraged homeowners to get rid of their lawns, which sounds like a good thing. Unfortunately, many homeowners chose a quick and inexpensive solution and replaced turf with gravel and a few low-water-use shrubs or succulents. These arid landscapes serve only to save water; they do nothing to enhance quality of life.

Evaporation and transpiration from trees, shrubs, groundcovers, and healthy soil covered with organic mulch provide shade, lower surface temperatures and reduce glare. This approach keeps urban areas cooler and more comfortable in hot weather, offers visual relief from a paved-over urban environment, and provides wildlife habitat. As stewards of the environment, we need to encourage clients to commit a portion of their precious outdoor water resources to supporting landscapes that help keep our cities livable.

Establishing a framework of hydrozones

We group plants with similar water needs together when we design a garden. For instance, low-water-use plants are kept separate from medium-water-use plants. This practice is known as “hydrozoning,” because the plants in each group can receive the same amount of water. When we develop a water budget, we divide the landscape into separate hydrozones depending on site conditions and plant communities. If the client wants some higher water-use plants, we place them in a separate hydrozone and locate them close to the house where the plants can be enjoyed.

To offset high-water hydrozones, we designate very-low or no-water-once-established hydrozones. Plants in these sections may go summer dormant, so they are located further away from view. Trees, which have high value due to their many benefits, are placed in their own hydrozones. After mapping out the hydrozones, we then select specific plants and create a planting plan. Laying out the hydrozones provides a framework for designing the planting and irrigation schemes and it sets up a system to prioritize stored water use in the event that outdoor watering becomes severely restricted or prohibited entirely.

Preparing for the worst case: a triage approach

Which plants should be saved if there isn’t enough water for all? Trees, especially established trees, are usually the highest value landscape elements. Next are the plants closest to an entryway, or mature shrubs that provide privacy.

Then we look at sources of water. If we can’t irrigate but want to save our trees, how much water should we make plans to capture and store? Many factors will determine just how much water the trees will need and when, but we can plug an estimate into our water budget at the design stage and use that amount to determine what size storage tank is necessary. Perhaps we can store enough water to irrigate more than just a few hydrozones; the amount of storage depends on the client’s budget and the space available for water storage.

If budget and space constraints don’t allow for capturing and storing significant amounts of water, then devoting a considerable portion of the garden to plants that, once established, can survive the dry season without supplemental watering is the best strategy.

Final thoughts and hopes

Planning for the new normal begins in the preliminary stages of designing any landscape. In addition to addressing aesthetics, functionality, client needs, quality of life, and costs, as designers we also consider the worst-case scenario. By answering the many questions posed in this article and devising creative solutions, our clients can be ready if or when that day comes. These challenges provide opportunities to design better and more resilient landscapes.

As El Niño fades, water agencies and municipalities will likely offer more generous rebates very soon to help defray the cost to install alternative sources of water. The rainwater harvesting industry continues to develop better and more cost-effective solutions for tapping alternative sources that we can all take advantage of. As designers, we are part of an exciting and concerted effort to redefine the look and functionality of California landscapes in our quest to successfully adapt to a changing climate.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses