Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need

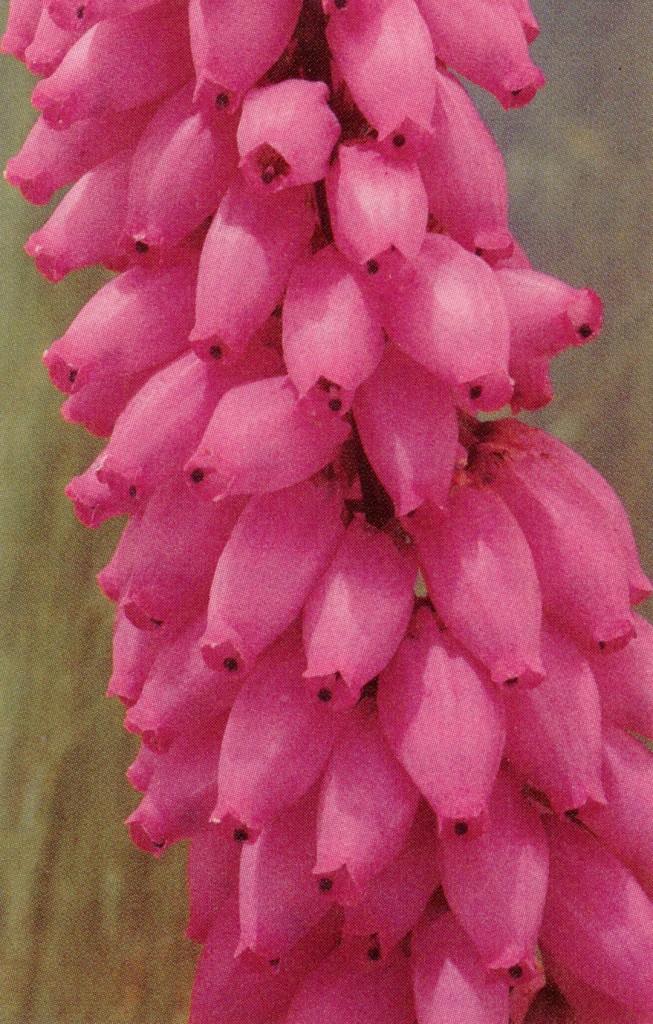

‘The short-tubed species in particular suggest the ceramic art at its best, and many of them might have served as models for the amphorae of Greece.’

Professor RH Compton describing Cape heaths,

quoted in Schumann, Kirsten, and Oliver, Ericas of South Africa

Cape heaths are interesting and striking members of Erica , a genus widely known because it also contains the commonly cultivated European heaths. Though they only account for about twenty species, the European heaths occur where they were sure to become known early to Western Civilization. They range from Lebanon and Turkey westward through Greece to Portugal and Morocco and outward to Madeira and the Canary Islands. Northward the genus extends through France and the British Isles to Iceland, to the North Cape of Norway, and to the southern shores of the Baltic Sea. (The European heaths gain a small amount of importance from the fact that Erica arborea yields the “briar root” made into tobacco pipes.)

About ten more species occur in scattered parts of East Africa, and forty-five species are reported from Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands. However, the remaining 650 species of Erica occur in a small part of southernmost Africa, south of the Limpopo River. These are the Cape heaths, which became known in Europe quite early because of their general nearness to the strategically located Cape of Good Hope. Linnaeus described twenty-three ericas in Species Plantarum and recorded twelve of them from the Cape of Good Hope.

In late eighteenth-century England, the Cape heaths became fashionable glasshouse subjects. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the Duke of Bedford, George Hibbert, and others amassed extensive collections, including many species no longer known in cultivation and some that are now rare or, perhaps, extinct. Toward the middle of the nineteenth century, the Cape heaths lost fashion to the European heaths, many of which grow easily out-of doors in England.

The concentration of Erica species in southernmost Africa is staggering. On the tiny Cape Peninsula, alone, there are well over one hundred species! How is such a concentration possible? How are species not lost through hybridization? In part the answer is that the Cape heaths present distinct appearances for bird and insect pollinators. Permutations fall upon permutations. Cape heath flowers are of every color save blue. Some are bicolored; some, tricolored. Some flowers are presented singly; some in groups. They vary in size and vestiture. Some are accompanied by ornamental bracts. Some hang down; some point upward. Stamens may be included or project far out. The basic heather “bell” is contorted in every way, and quite as remarkable is the botanical vocabulary describing Cape heath bells: “elongate ampullaceous,” “tubular hypocrateriform,” “oblate globose,” “depressed oblate urceolate,” “broad cyathiform,” “clavate tubular curved.” In this strained talk is a horticultural message: among the Cape heaths is a bell just right for anyone.

Santa Cruz Successes

The UC Santa Cruz Arboretum has grown over fifty species of Cape heath to date, as a part of our extensive South African collection. Situated at the northern end of Monterey Bay along the central California coast, the arboretum is in a special place, well-suited for the cultivation of these ericas. Our well-drained, acidic, sandy-loam soils are ideal, and our southern exposure, marine influence, and good luck have kept us frost-free over most of the property for nearly thirty years. We placed the Cape heath bed in an area of full sun, provided the plants with drip irrigation at two-week intervals (during the dry season), and mulched the bed deeply with pea gravel. The severe December freezes that struck California in 1990 and 1998 were tough on many lowland South African plants including ericas, although many survived and thrived.

Following are descriptions of a number of sturdy ericas that are worth trying over much of coastal California and perhaps beyond. The hardiest ericas are likely tucked away in South African mountain niches where regular frosts occur. When seed from these populations are grown, many more ericas will be seen in gardens throughout the West, including more interior locations. The following species all survived the December 1990 and December 1998 frosts in Santa Cruz, except where indicated otherwise.

Erica cerinthoides is the most widespread of all South African species, occurring from the winter rainfall region of the Cape Peninsula east to the summer rainfall regions of the Drakensberg and Transvaal. A wide range of color variation is found in the wild, including a white-flowered form. Regular pruning and cluster planting are recommended as this cultivar tends to grow a bit loose for a few years. Erica cerinthoides has a lignotuber and will resprout following a fire, so adult plants are likely to respond well after pruning. (One of its common names is fire heath.) With a little spring feeding and summer watering, flowering should last for four months, from early spring to summer. Year-round flowering is reported in the wild so with the addition of several clones or seedlings, a long show in the garden could be achieved. Erica cerinthoides ‘Scarlet Santa’ is a small shrub, two to three feet high and about as wide. It is packed with flower clusters at the ends of the branches. Individual flowers are beautifully inflated, cigar-shaped scarlet-red tubes, two inches long. This is over half an inch longer than the typical length of the floral tube for this species!

Erica cerinthoides and E. oatesii belong to the subgenus group Dasyanthes. Erica oatesii is from the summer rainfall area of eastern South Africa, where it is reported to grow along mountain streams. In Santa Cruz, it has grown well and flowered profusely. So far, we have only seen the scarlet or deep red forms though many color variants are noted in the wild. Erica oatesii is a small scale E. cerinthoides, with a much tighter and denser habit, growing less than one foot high.

The Evanthe group is characterized by showy, tubular flowers, borne at the ends of lateral branches and includes forty-eight species, many of which have been grown at the arboretum. Erica versicolor, E. speciosa and E. discolor are similar in appearance and all three make beautiful garden plants. Erica versicolor can grow to over six feet in height, but will flower more profusely and perform best in the garden if pruned annually after flowering. Its tubular flowers, red with green tips, are showy and are produced in dense clusters. Erica speciosa and E. discolor are almost indistinguishable from one another. They are both strongly branched, tough shrubs, bearing deep green foliage with red tubular flowers. Erica speciosa has slightly longer leaves and anthers of a different shape; it occurs in moist habitats while E. discolor occurs on dry rocky outcrops.

Erica curviflora is another prolific grower in the Evanthe group; its flowers are red, flared, curved, and tubular. It is found along streams and has performed especially well at the Arboretum with twice-monthly summer irrigation. Others in the subgenus that have been grown successfully in Santa Cruz are E. pattersonia, E. densifolia, E. hebecalyx, E. diaphana, E. perspicua, E. verticillata, E. cruenta, and E. brachialis.

The Orophanes group includes thirty-six species with bell- or urn-shaped flowers. Orophanes means “mountain appearance” and acknowledges the mountain habitat of most members of the group. Erica lateralis is one of our favorites and is certainly one of the most beautiful ericas in cultivation, covered in summer with masses of pink flowers. The individual bells are held out from the branchlets on pedicils, tipped to show the much darker purple anthers inside. The plants are rugged and grow a little over two feet high and will reach six feet across. Erica lateralis is widespread in nature, occurring at elevations over 3,000 feet.

Erica irregularis, E. quadrangularis, and E. mauritanica, also in the Orophanes group, are similar to one another, having deep purple bells massed over small shrubs about two feet wide by three or four feet high. All are striking.

Erica formosa has no trouble living up to its name, which means “beautiful” in Latin. It is a small shrub, less than two feet high, that is encased in swollen bell-shaped white flowers at its peak.

Erica bauera and E. mammosa are members of the Pleurocallis group; they are tall (over six feet) and somewhat leggy, with long, striking tubular flowers produced in almost any month of the year. Their legginess can be offset by placing lower shrubs at their base. Prudent pruning immediately after flowering can also produce a denser habit and postpone senescence. Both species sport flower colors ranging from white to pink to red. Erica bauera is distinct with its gray-green leaves, while E. mammosa can be identified by the dents at the base of the corollas.

Erica grandiflora, another member of the Pleurocallis group, has flared tubular flowers ranging from golden-orange to red, with anthers extending well beyond the corolla. The leaves are needle-like and somewhat longer than on most species. This species has made regular volunteer appearances in the garden.

Erica vestita, a fourth member of this group, is similar to the last, with needle-like leaves but with anthers that remain inside the corolla. The combination of deep red flowers against luxuriant green foliage is spectacular.

The flowers of Erica glauca var. elegans and E. monsoniana present a generous use of bracts and floral leaves as part of the floral show. Erica monsoniana is a montane species with white sepals, petals, and bracts creating a lovely fluffiness to an otherwise rather stiff woody shrub. Erica glauca var. elegans is a compact shrub with blue-green foliage and striking reddish-pink to reddish-plum corollas, sepals, and bracts. The bracts extend well down the stem creating a handsome effect. It is not clear whether this species was killed in the 1990 freeze.

Erica regia var. variegata is popular in South Africa as a garden plant. It has not survived our big freezes but perhaps would do so with more shelter from the early morning sun during frosty spells. It has a striking color pattern on the floral tube: white at the base grading into green and purple to orange or red and tipped in deep red.

Ericas are well suited to the coastal region of California, where the right circumstances of acid, well-drained soils, and moderately frost-free sites can be provided. They can fit into any size of garden and are useful as container plants and for cut flowers. Although it is unlikely that any would become weeds in the American West, it is always best to be cautious and delete any that reseed too generously.

An excellent reference, beautifully illustrated, is Ericas of South Africa by Dolf Schumann, Gerhard Kirsten, in collaboration with EGH Oliver, published in 1992 in South Africa by the Fernwood Press.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses