Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need

Too great a brilliance, or too much of it, will create a sense of surfeit in years to come. The toes, like the lawn, are the framework and background to our colourful shrubs and border plants.

Graham Stuart Thomas, Trees in the Landscape

The cultivated landscape of the Pacific Northwest draws on many borrowed ideas, most of which have come from the northerly latitudes and colder climates. Even though snow is headline news west of the Cascades and our winter color is green, something about our rugged coniferous backdrop seems to call for the ambience of northern Europe, New England, or even the prairies of the Midwest. The occasional bad freeze lends the weight of logic to the widespread feeling that plants from warmer climates do not belong here.

Lost in all of this is the richness and diversity that comes from a more cosmopolitan plant selection. Most notably missing from many Northwest landscapes are broadleaved evergreen trees. While one of the handsomest of these, the madrone (Arbutus menziesii), is an abundant native, few others are commonly grown or even widely known among gardeners in this region.

We would do well to welcome more broadleaved evergreen trees. When drizzly skies blend streets and buildings into a wash of grays, the sparkle of living greenery overhead can be a powerful tonic. And where there is harshness to soften or ugliness to hide, we need the camouflage of foliage year round. For these purposes, trees need to be evergreen, and conifers are not always appropriate in shape or character.

The potential of broadleaved evergreen trees has begun to attract more notice in the Northwest, but for those who have caught the spirit the problem remains one of availability. Nurseries carry a few thoroughly proven kinds, especially the evergreen magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), Fraser photinia (Photinia x fraseri), and English holly (Ilex aquifolium), but hesitate to stock other little-known plants. They await a bigger demand and assured sales, while designers and gardeners wait for the nurseries to offer, and guarantee, these plants. Until more risks are taken on both sides, this impasse will be difficult to resolve.

Perhaps we should begin by clearing up a few misconceptions. First, dozens of broadleaved evergreen trees are hardy west of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington; they have proven themselves in the few places they have been tried. Second, they are as easy to grow, and about as fast, as other groups of plants, though they vary widely in their particulars. Finally, not all broadleaved evergreen trees shroud everything beneath them in perpetual shade; some are light and airy, and a few of the best thin out a bit for winter. In short, broadleaved evergreen trees are a varied bunch with much to offer the landscaper and gardener.

Broadleaved Evergreens for the Northwest

The trees and large shrubs described below have all weathered enough winters in Washington and Oregon west of the Cascades to have proven their hardiness here. They are introduced in alphabetical order by Latin name for easy reference. Plants from A through L are included here; the remainder will appear in the next issue.

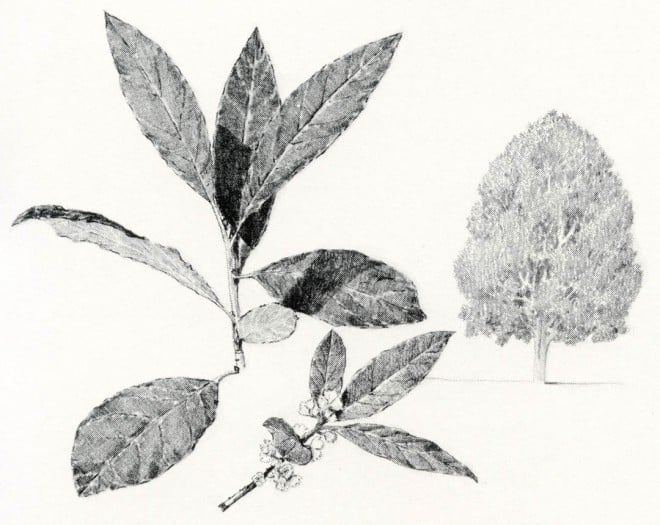

The native madrone (Arbutus menziesii) is fussy in cultivation; whether natural or planted, it needs to be left alone. There are several relatives in the genus that sometimes show up in collections. All are smaller variations on the theme of glossy, oval leaves, red fruit, white flowers, and reddish, peeling bark on a sinuous framework. Only the strawberry tree (A. unedo), native to Ireland and the Mediterranean, is at all common in the Northwest. While usually used as a shrub, this small-leaved plant can reach fifteen feet or more. Besides a fall and winter display of creamy flowers and orange-red fruits, the strawberry tree offers ease of cultivation in any well-drained soil.

The boxleaf azara (Azara microphylla), from Chile, has perhaps the smallest leaves of any broadleaved tree. Oval, shiny, dark green, and barely half an inch long, they are neatly arranged along slender twigs to form a diaphanous fifteen- to twenty-five-foot crown. Plants in warm, sheltered spots may produce small, yellowish, chocolate-scented flowers in late winter. Azara is best in a woodland edge.

Camellias are abundant in the Northwest as shrubs, reaching rooftops only in age. But a few of the best tall ones could be planted as small trees in semi-shade. In addition to the usual cultivars, some rarer species make handsome trees. Camellia pitardii, with beautiful pale rose flowers, and the pink-flowered hybrid between C. japonica and C. cuspidata make especially nice fifteen- to twenty-foot specimens in the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle, where some cultivars of C. reticulata also are proving hardy.

The golden chinquapin Chrysolepis chrysophylla is a glamorous native that begs to be brought into the garden but usually pouts when planted. Our few good garden specimens of this chestnut relative are growing in well-drained, rather shady sites. With pale bark and narrow leaves backed with gold felt, the chinquapin is well worth the effort to satisfy it. The tree is rare in the wild in southwest Washington, more common from central Oregon south, where it may exceed seventy feet.

The evergreen dogwood (Cornus capitata) has had a spotty career in the Northwest, and few remain after our recent cold winters. Still, a handful have survived, suggesting that selections from local trees might bring this beautiful plant into wider use here. Broad and bushy, this Himalayan tree carries a crop of pale sulfur flower heads and big raspberry-red fruits against a backdrop of sea-green leaves. It rarely exceeds twenty feet.

Among the cotoneasters are some pleasant small trees, perhaps the best and most common being Cotoneaster salicifolius, the willow cotoneaster. With narrow leaves and thin, often horizontal, branches, it makes a graceful multi-stemmed tree to fifteen feet or so. Fall and winter find it laden with generous clusters of bright red fruit, especially in the dry, sunny situations it prefers. All the larger cotoneasters need some pruning to attain and keep good tree form.

A hybrid evergreen hawthorn, Crataegus x grignonensis, makes a tree much like the common C. monogyna but with bigger leaves. It passes the winter with a good crown of green leaves, which may drop by spring in coldest winters, and a crop of large, edible, red fruit. Little known here but well proven in Europe, this hawthorn would seem a good prospect for the Northwest, where at least one plant I know is thriving handsomely. It may be rather shrubby unless top grafted.

The loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) appears now and then in Northwest gardens and may even yield its luscious fruit to those who give it a warm, sunny spot. Its large, corrugated leaves are reason enough to grow this surprisingly hardy subtropical, which can reach twenty feet or more.

Eucalypts

The eucalypts (Eucalyptus spp.) are perhaps the most controversial trees on this list. Nearly everyone seems to like them and want to grow them here, but there is skepticism concerning their hardiness. The recent string of record freezes has left doubts and confusion. Still, it is clear that several of these willowy, aromatic Australians are hardy west of the Cascades, and many others are worth a trial in sheltered situations.

The list of truly hardy eucalypts would have to include the snow gum (Eucalyptus niphophila), a sixty-foot tree with blue-gray leaves and smooth, ivory bark, the similar but larger E. pauciflora subsp. debeuzevillei, and the small-leaved E. archeri. All three survived the cold (down to 0° F. in some places) while other species perished, and all are strikingly handsome.

Heading the near-hardy list of eucalypts is the cider gum (Eucalyptus gunnii), of which E. archeri may be only a bluer and hardier form. This tree has long been rated the hardiest in Europe, but Northwest specimens have shown disconcerting variability on that score. Our largest cider gums are sixty to seventy feet tall. Other nearly hardy eucalypts doing well in some Northwest gardens are the spinning gum (E. perriniana), with silver-dollar juvenile leaves, and the cabbage gum (E. parvifolia), a bushy, small-leaved tree. Both of these grow to about thirty feet. More tests and selection surely will lengthen the list of these colorful, fast-growing trees for the Northwest.

The genus Eucryphia, of the southern hemisphere, supplies us with several species and hybrids of choice, mostly evergreen small trees. Perhaps the best of them in hardiness and form are E. x intermedia ‘Rostrevor’ and E. x nymansensis, both coming to us via the British Isles. The former gets its delicate texture from the tender E. lucida and its hardiness from the deciduous E. glutinosa. It makes a broadly oval, richly green shrub or small tree to twenty feet or more. Its companion is a coarser tree quickly reaching fifteen feet, then gradually thirty feet or more. Both are studded with showy flowers, like single white roses, in late summer. Eucryphias need a well-drained, highly organic soil.

Hollies

The hollies (Ilex spp.) include some of the hardiest broadleaved evergreen trees. The standard bearer of the genus, I. aquifolium or English holly, is clipped and sent nationwide from the Northwest at Christmas, and the tree has become naturalized in our suburban woods. There are dozens of other hollies, little seen in nurseries, that deserve our attention.

Two hollies, Ilex latifolia and the hybrid I. ‘San Jose’ stand out for their large leaves. The former has bigger leaves, up to ten inches long and four inches wide, but the latter offers showier red berries. Both are narrowly oval trees growing twenty to thirty feet tall. The hybrid Highclere hollies (I. x altaclerensis) take dark, shiny elegance to the extreme in their large, patent-leather leaves. Two cultivars, ‘Camelliifolia’, with oval, nearly spineless leaves, and the recently popular ‘Wilsonii’, with rounded, evenly spined leaves, are usually available. They are both pyramidal unless trained otherwise.

Perhaps the most interesting hollies on the list are three spineless ones. Ilex pedunculosa, the longstalk holly, displays its small red berries, each on a slender stalk up to one and one-half inches long, against lush masses of pointed, wavy-edged leaves that suggest Ficus benjamina. But tropical it is not; longstalk holly has endured temperatures well below zero in the Eastern states.

The Japanese Ilex integra is another Ficus impostor. Its broad, bushy form and thick, oval leaves are amazingly like those of the Indian laurel fig (Ficus microcarpa, sometimes erroneously called F. retusa). This one is hardy to Zone 8 and seems ideal for a tall screen or standard tree. Biggest of the three is I. chinensis, whose large, thin, lime green leaves make a light, irregularly pyramidal crown to sixty feet. This is the most exciting of the lesser-known hollies and, judging from the fine specimens at the Washington Park Arboretum, it has great potential.

Though long available in the Northwest, the bay tree (Laurus nobilis) has shown enough ambivalence during our winters to have missed becoming really popular. There are many fine, healthy bay trees here, but the occasional specimen imported from California will freeze back, so doubts about the tree’s hardiness persist. Trees from sturdy, preferably local, stock are hardy in most places, and the plant makes a bushy specimen fifteen to thirty feet tall. Besides growing well in most soils and exposures, this classic Mediterranean evergreen adds historical and culinary interest to its landscape appeal.

The glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum) also has been available for some time, but only lately have we begun to use it as a tree. Successful public plantings in Seattle and elsewhere have shown this neat, rounded tree to be hardy and streetwise. Under the usual dismal curbside conditions, glossy privet will grow slowly to fifteen to twenty-five feet; in decent garden soil it may be a little faster and reach twice the size. Its pyramidal clusters of small, creamy flowers and black berries are fairly showy. On poorer soils, the glossy privet is dramatically improved in growth and color by an annual application of an all-purpose fertilizer the first few years.

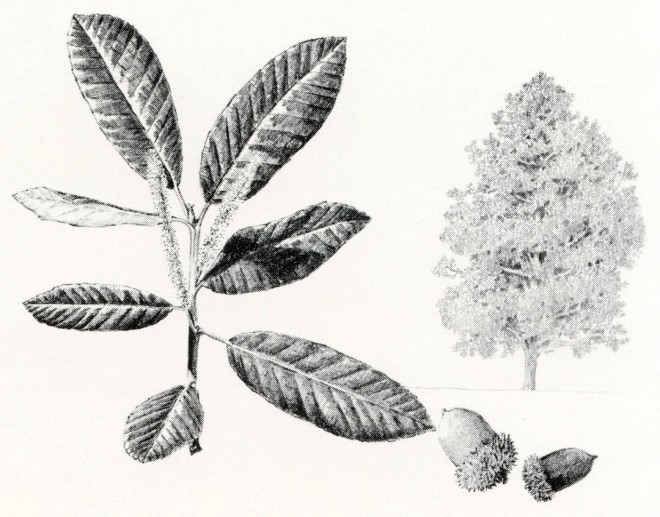

The tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus), which enters our flora in southwest Oregon, has always been unaccountably overlooked in Northwest plantings. An attractive tree with embossed, medium-green leaves, it grows well in sun or shade. Though it may be a giant, slow-growing shrub in open exposures, in woodland tanoak assumes a tall, open form that, with its whitish bark, resembles an evergreen alder. It is hardy in all but the coldest zones west of the Cascades.

Sources of Trees

Beaver Creek Nursery

7526 Pelleaux Road

Knoxville, TN 37938

(615) 693-7533

Camellia Forest Nursery

125 Carolina Forest

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Forestfarm

990 Tetherpah

Williams, OR 97544

(503) 846-6963

Gossler Farms

1200 Weaver Road

Springfield, OR 97478

(503) 746-3922

Whitman Farms

1420 Beaumont Street

Salem, OR 97304

(503) 363-5020

Wayside Gardens

Hodges, SC 29695

(800) 845-1124

Some trees mentioned in our article are grown by wholesale nurseries and shipped to retailers. If your local nursery hasn’t what you want, ask whether they will order it from Monrovia Nursery Company, Leonard Coates Nurseries, or one of the other wholesalers.

One of the Asiatic tanoaks, Lithocarpus henryi, is showing much promise here. Growing perhaps to sixty feet, it has bright green, long, pointed leaves that give the tree an assertive texture. Healthy in Seattle after several cold winters, this striking evergreen is ready for wider planting.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses