Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Wolves, Crabs, and Other Wandering Spiders

Since long before Miss Muffet was scared off her tuffet, people have feared spiders. She would have done better to be wary of her father, who dosed her with spiders as medicine—a not uncommon remedy in times past. Spiders, however, have done little to warrant their sinister reputation. Worldwide, only about twenty-five species are dangerous to humans, and most of these are not aggressive. In the West, the only seriously venomous spider is the shy, nocturnal, and easily avoided black widow. Yet, despite the considerable contribution spiders make in pest control, it can be difficult to overcome the fear. Even the occasional entomologist, while professing a love of insects, may be openly arachnophobic. “Too many legs!”

Spiders have eight legs, two more than insects, and are part of the class Arachnida, which includes several familiar orders of arthropods such as scorpions, ticks, and mites. Spiders, in the order Araneae, have only two main body parts: the abdomen, and the cephalothorax, analogous to the fused head and thorax of insects. (The closely related order Opiliones includes the daddy-long-legs, or harvestmen, recognized by having only one main body part.) All spiders make silk, a special protein strand produced by spinneret glands, during all their life stages. Ecologically, spiders can be divided into those that build webs for snaring prey, and those that wander, using silk for other purposes. We will leave snare builders for another time, and here explore the wanderers

The Wonders of Silk

In addition to webs and a variety of ingenious snares, spider silk, which is half as strong as steel and twice as elastic as nylon, is put to myriad uses: nests, egg sacks, and draglines that anchor spiders safely to the substrate at intervals. Ballooning spiderlings (baby spiders) of some species continuously produce silk strands until they are caught by a passing breeze and float away to a new home, sometimes transported vast distances. Spiders, with few exceptions, also have poison glands; venom serves for killing prey, and as a defense against predators. Spiders are generally timid, and most won’t bite even when handled; many are unable to pierce human skin. Most spider bites are no worse than a wasp sting, and some of the most ferocious-appearing spiders, the so-called “tarantulas,” are so gentle that they are popular pets.

True spiders (suborder Araneomorphae) have fangs that can move sideways; included here are crab and wolf spiders, jumping spiders, orb weavers, and other families. The giant hairy pet spiders commonly called ‘tarantulas’ are not true tarantulas (a type of wolf spider), but belong to a different suborder, the Mygalomorphae, distinguished by fangs that are joined at the front of the head; they can only strike forwards and down. Besides ‘tarantulas,’ the Mygalomorphae include trapdoor spiders, which make a silken nest in the soil, venturing forth at night to look for prey, and purse web spiders, which live their entire lives in a silken tube through which they capture unwary insects.

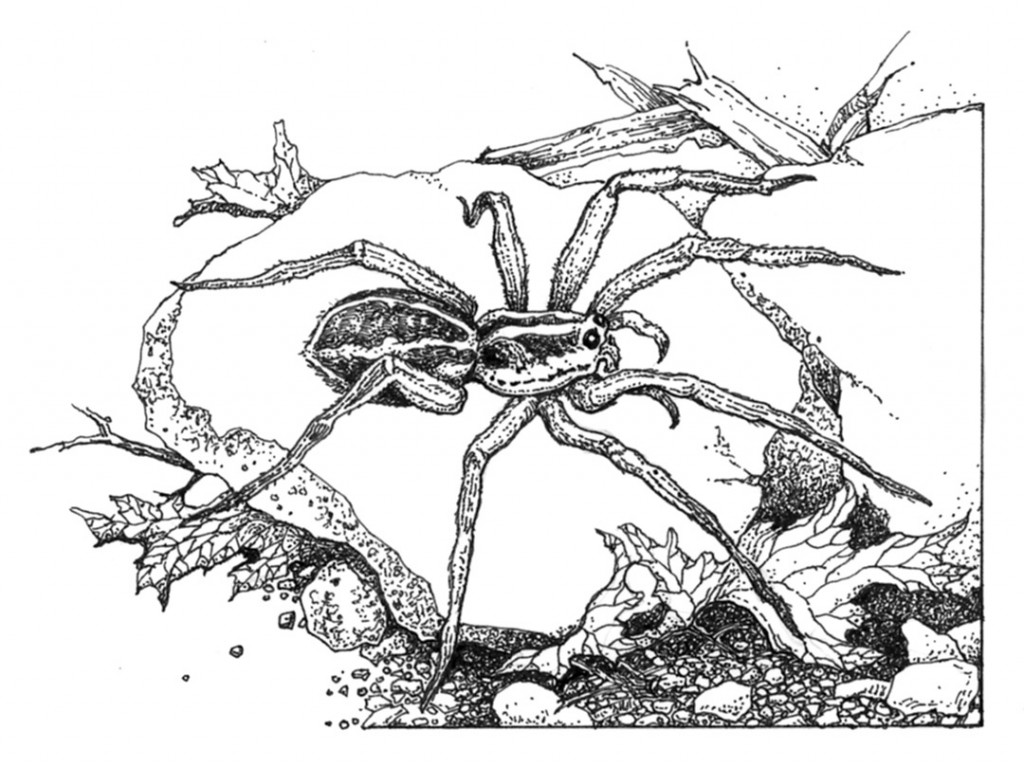

Wolf spiders, along with jumping spiders and crab spiders, are frequently encountered garden denizens. Wolf spiders are common, and easily recognized as they run out of mulch and ground cover when watered, the females often with an egg case attached to their spinnerets. You may see newly emerged spiderlings riding about on the mother’s abdomen. Despite their name, wolf spiders are solitary, and are usually ambush predators.

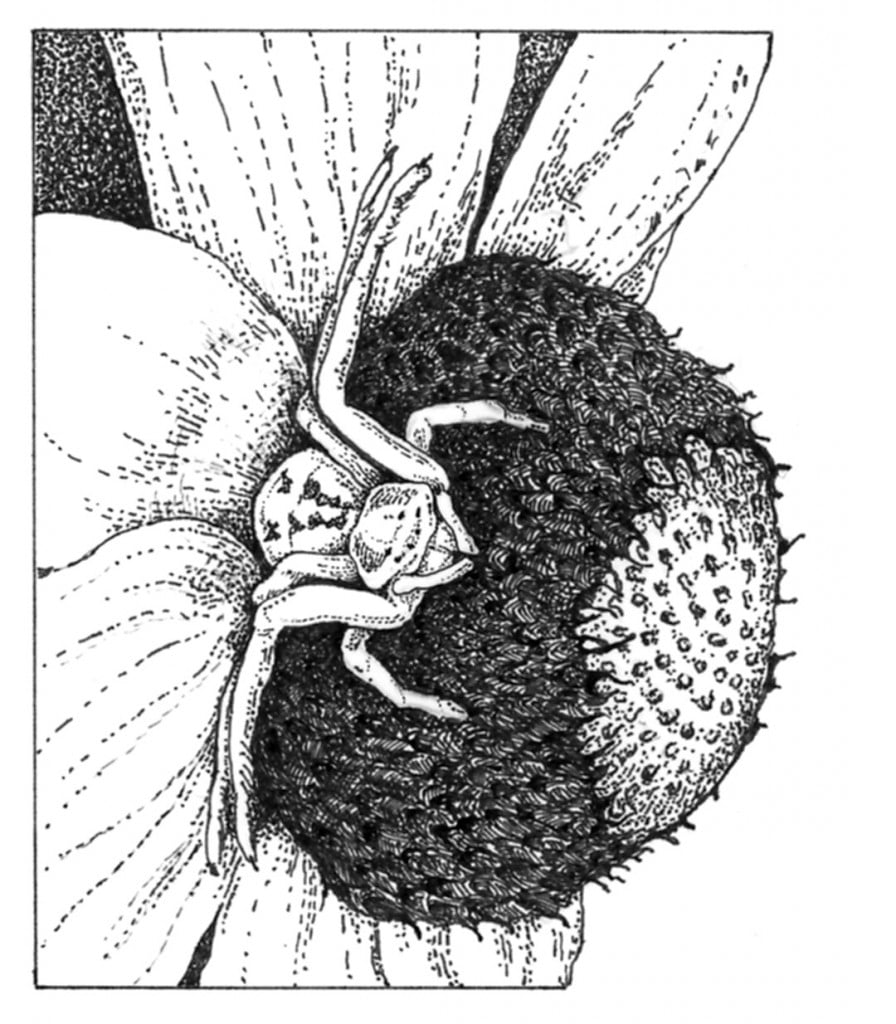

Crab spiders are also ambushers. Although they are found in a variety of habitats, they are most often noticed sitting motionless on blossoms, where they prey on visiting insects. Named for both their appearance and ability to move dexterously sideways, crab spiders are often beautifully camouflaged, blending with their floral background. They do prey on beneficial pollinators, but are not so abundant as to pose a problem.

Jumping spiders are active hunters, stalking prey and pouncing once in range. Their eyesight is acute, and they will scurry to the other side of a stalk or leaf when too closely watched by an inquisitive gardener; the two large central eyes give them a look of curiosity when peering back at an observer. Most spiders are active at night, but many of the wandering spiders are active at dusk or in daylight.

Beneficial Generalists

Spiders are generalist predators, but most are not indiscriminate in their choice of prey. While crab spiders sometimes eat beneficial insects, including bees, many spiders avoid stinging hymenopterans and rely on a wide variety of flies, small beetles, and true bugs. Generalist predators were once thought to be less effective in suppressing pest populations than specialists, but recent studies have shown that spiders are critical to pest regulation in many habitats. Spiders also provide an important food source for other invertebrates, as well as reptiles, amphibians, and birds. Some spiders are associated with certain plant species; careful observation will serve the gardener well in this regard. Ground covers and bunch grasses provide valuable habitat, and leaf litter is an important over-wintering resource.

It wasn’t really so strange that Mr. Muffet fed his daughter spiders. There may well be an association between good health and the presence of spiders, although eating them is probably ill advised. Many disease-carrying flies, it turns out, are favorite spider prey, yet another reason that it is a pleasure to encounter the helpful wandering spiders in the garden.

In A Nutshell

Popular Names:

Wandering and hunting spiders. Wolf spider, crab spider, jumping spider, and many others

Scientific Name:

Class: Arachnida. Order: Araneae. Suborders: Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae

Common Families:

Lycosidae (wolf spiders), Thomisidae (crab spiders), Salticidae (jumping spiders). Spiders that use silk for snaring prey will be featured in a future column.

Distribution:

Worldwide, over 40,000 species in over 100 families. West Coast, about 1,000 species. Numbers are in flux, with frequent additions, and a subject of ongoing controversy.

Life Cycle:

Number of molts depends upon species and gender, with males undergoing fewer molts, as do smaller species.

Appearance:

Eggs: always in a silken cocoon of varying shapes (spheres, teardrops, discs) attached to a substrate. Juveniles: a smaller version of the adult form. Adults: females and males look virtually the same until the last molt, when males manifest enlarged pedipalps (a pair of appendages in front of the legs) that are used in a complex and unique method of reproduction. Spiders range from virtually microscopic to the world’s largest, with a body length of 3.5 inches and a spread of eleven inches across the legs.

Life Span:

In temperate zones, usually one year, sometimes two. Some spiders live for many years, and can take up to eight years or more to reach maturity. Only females have a long life expectancy; males usually die soon after mating.

Diet:

Predacious on insects, mainly flies; sometimes also other arthropods, such as millipedes, sowbugs, and even other spiders. Many spiders can survive for months without food. A single species of crab spider (Bagheera kiplingi) has recently been discovered to be an herbivore.

Favorite plants:

Bunch grasses, ground covers (wolf spiders), straw and other organic mulches. Crab spiders like flowering plants and are abundant on flowers of the aster family (Asteraceae). Most spiders overwinter in leaf litter.

Benefits:

Spiders prey on many pests, and are themselves food for other beneficial garden residents.

Problems:

Spiders prey on beneficial insects as well as pests. Some may bite.

Interesting facts:

The study of spiders is called arachnology. Many wolf spiders can run on water as well as they do on land. The water spider lives its entire life underwater in an air bubble that it traps beneath a specially built web. The turret spider makes a tower above its terrestrial silk-lined burrow, decorated with available materials such as pine needles, moss, and lichen; it perches at the entrance, watching for approaching insects. Dune spiders cartwheel rapidly (twenty revolutions per second) down sand dunes when escaping their fierce enemy, the spider wasp. Most spiders can lose a leg when in danger, and replace the lost leg at the next molt (although it may be smaller).

Sources:

Many species found in gardens.

More information:

www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PDF/PESTNOTES/pnspiders.pdf

www.washington.edu/burkemuseum/spidermyth

https://www.awesomespiders.com

https://spiders.ucr.edu offers information on the brown recluse, which is not a resident of most of the West Coast.

Spiders of the World, Rod and Ken Preston-Mafham (1984). Spider basics, beautiful photographs; written from a British perspective.

www.wikipedia.org has a well-written section on spiders.

Responses