Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Good gardeners and plantsmen, just as good gardens, evolve as they mature—putting down deeper roots, becoming richer in their diversity and complexity.

John Whittlesey, owner of Canyon Creek Nursery and Design in Oroville, California, is an exceptional plantsman. A naturalist in his youth, he grew into an apprentice nurseryman, and founded a specialty mail-order nursery of international renown. In 1986, Whittlesey wrote, typed, and direct-mailed his first sixteen-page Canyon Creek Nursery (CCN) catalogue filled with hard-to-find cottage garden plants. Its cover was illustrated with simple line drawings of a violet, a dianthus, and a geranium, drawn by his artist/educator wife Susan.

When the final catalogue was mailed in 2004, the nursery and its owner had matured from a focus on growing plants for different climates around the country to a greater sensitivity to design and environmental advocacy specific to the American West. The final catalogue contained more of Susan’s detailed illustrations. The cover image, featuring a floriferous hybrid sage (Salvia xjamensis) rooted in almost animated duff below, with birds, bugs, and pollinating butterflies, symbolically illustrated the direction, interest, and growth of Whittlesey’s educational journey.

The CCN catalogue, at its peak, boasted forty-four pages of specialty perennials—some developed by Whittlesey—and offered many California native and drought-tolerant mediterranean-climate selections. Five thousand catalogues were printed a year, and upwards of 2,000 orders were shipped. Over the years, the catalogue grew to include recommendations for companion planting, climate-appropriate plant care, and a select handful of gardening books. References in themselves, Whittlesey’s catalogues included caring and colorful—but precise and never overblown—descriptions of how each plant has performed in his climate. CCN became as much about respecting the uniqueness of each place and developing good gardening practices as about supplying plants.

Whittlesey stands about six feet tall, his graying wavy hair and trim beard framing a friendly face with thoughtful, smile-creased eyes attesting to sun and fresh air; he always seems ready to hike or work in the dirt with you. He and CCN came of age in the almost twenty years of the nursery’s mail-order identity. Decades of keen observation have led to a deep appreciation and growing sense of advocacy for regional sustainability and for native or climate-appropriate plants and garden design.

The Early Years

Whittlesey was born in 1953 in Cleveland, Ohio, to David Whittlesey, a mechanical engineer, and Jean Whittlesey, a librarian with a background in biology and a love of the natural world. Whittlesey was one of three brothers and two sisters; before he was five, his family made the move west to Fair Oaks, outside Sacramento, California. After his parents divorced, he and his siblings remained in Fair Oaks with their mother. The plants and trees of the community left long-lasting imprints on Whittlesey.

An interior live oak (Quercus wislizenii) stood sentinel along the driveway of the family’s farmhouse, which his mother called “Hollyhock Hill.” He describes the tree as

. . . majestic, with two huge branches; the one arching out over the gravel driveway above the lawn was hung with a swing, the other headed for the sky and split into several horizontal limbs. The garden had tall pecan trees, lawn for playing, and interesting shrubs planted by the farmer/nurseryman who built the house.

Whittlesey’s fourth grade science project was on mushroom spores. In the basement of the simple white farmhouse, Whittlesey remembers “a corner with an old microscope, where I studied pond water for the seventh grade science fair. I’d spend several hours a day observing and sketching the microscopic pond life.”

At the Fair Oaks house, Whittlesey’s affection for violets developed; in 1987, he selected and named a cultivar ‘Fair Oaks’ in tribute to this garden.

Carpets of violets bloomed in January and February— mostly purple, some pink ones, and lots of the purpleveined, white-petaled confederate violets (Viola sororia). I started growing some of the more rare Parma violets in my late teens and sold them to Western Hills Nursery in Occidental and Beecher’s Nursery outside of Stockton. I also grew many geraniums (Pelargonium). At one time, I had sixty scented geraniums, along with 200 others of different types: zonal, ivy, and species. I immersed myself in the Geraniaceae. I am not a collector of things by nature, but when I become interested in a group of plants, I begin a circle of getting to know them better.

In his late teens, Whittlesey familiarized himself with the wider horticultural scene and its personalities. He would drive to San Francisco for Monday night meetings of the California Horticultural Society, meeting some of the “legends” of Northern California horticulture, such as Ed Carman, Victor Reiter, Marshall Olbrich, Lester Hawkins, and Wayne Roderick. “I was one among many young plantspeople encouraged by them—especially by Marshall. I feel lucky to have known them.”

Whittlesey’s passion for growing plants continued as he pursued studies in horticulture, chemistry, physics, and botany. Later, John and Susan moved as a young married couple to Spokane, Washington, where Whittlesey worked for Spokane’s venerable Lamb’s Nurseries. He reorganized and updated the decades-old nursery and improved its efficiency. His apprenticeship under owner Hideki Sekijima taught Whittlesey how to run a mail-order nursery. Although Sekiyama hoped he would take over the nursery, Whittlesey knew “Spokane was a fine city, but not our home.”

Canyon Creek Nursery

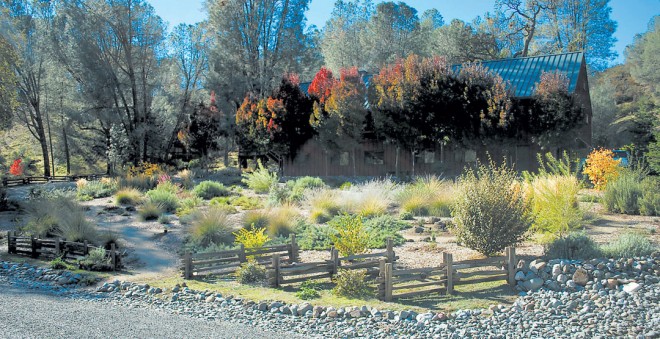

After a European nursery and garden tour in 1984, collecting plants to start their new life, John and Susan Whittlesey found their home-of-a-lifetime on ten beautiful acres of rolling oak grassland and riparian corridor outside of Oroville, California. There, Canyon Creek Nursery was born, its first public appearance being a 1985 advertisement in the Winter issue of Pacific Horticulture.

Whittlesey’s initial collection for the nursery was built on traditional and uncommon cottage garden plants. He is justifiably proud of his early offerings of Euphorbia, hardy Geranium, Kniphofia, and Salvia. His plants represented the leading edge of interesting, hardy perennials satisfying the seemingly endless appetite of gardeners from the 1990s onward.

Violets, while a small part of CCN’s initial offerings, increased significantly through the years.

I’ve always liked fragrant leaves and flowers, have always enjoyed growing scented geraniums, jasmine, witchhazel, daphne, viburnum, wintersweet . . . . I like how fragrance goes directly to the primitive brain, recalling emotions and memories.

Whittlesey has rescued several violets from obscurity and reintroduced them into cultivation, including Viola ‘Double Russian’, ‘Mrs David Lloyd George’, and ‘Countess of Shaftesbury’. He has introduced many others into the United States from Europe and Australia.

By 1996, CCN offered a remarkable forty-six named violas and violets, as well as many selections of Agastache, Aster, Euphorbia, Kniphofia, Origanum, and Salvia. Every year, CCN’s solid word-of-mouth reputation grew in tandem with Whittlesey’s thoughtful selection of distinctive plants. The 1996 catalogue described his “intuitive, personal” approach to choosing plants and his desire to stay open minded about plants he was not yet aware of or familiar with. It concluded: “So I will try to stay awake, keeping my eyes, mind, and heart open.”

Whittlesey was not simply open to new plants, but also to a growing awareness of the importance of region and climate for successful gardening. In the late ’90s, CCN’s selections highlighted colorful, habitat-friendly, and drought-tolerant perennials. Artemisia, Agastache, Calamintha, Eriogonum, Monardella, Nepeta, Origanum, Penstemon, Phlomis, Salvia, Thymus, and Zauschneria, among other native and adapted plants, were proudly offered alongside Viola, Dianthus, Geranium, and other, more traditional cottage garden plants.

Deepening Roots

Fame and public acknowledgement were never on Whittlesey’s agenda, even though, over the years, he was acclaimed by organizations and publications such as Garden Design and Martha Stewart Living. He shipped plants to and compared notes with public gardens around the country, including Wave Hill, New York Botanical Garden, Longwood, Heronswood, Turkey Hill, LA County Arboretum, and Denver Botanical Garden. Home gardeners’ letters, questions, and feedback were just as memorable and satisfying, “with long-lasting relationships renewed every spring.”

As CCN broadened its reach and reputation, and Whittlesey became known in the world of “public horticulture,” he was also taking notes on gardening and life from the vantage point of his garden in Northern California’s bioregion. Purposefully following his own “circling” dance, Whittlesey learned more about the native plants, mushrooms, birds, butterflies, and ecosystems of his home region. He became more closely tied to his local horticultural community when he began selling his specialty perennials at the year-round farmers’ market in nearby Chico, California.

He became an active member of the California Native Plant Society’s Mt Lassen Chapter, serving as the horticulture chair and writing regularly for their publication, The Pipevine. He began leading native plant identification hikes to destinations such as the Warner Mountains, Snow Mountain Wilderness, and Mt Eddy in Shasta-Trinity National Forest. He lectured on specific plants like Salvia, as well as on broader concepts (Gardens as Habitat, Gardening with Natives, Native Plant Propagation, Lawn Replacement, and Integration Techniques) for organizations such as the Northwest Horticultural Society, Chico State Herbarium, the Audubon Society’s annual Snow Goose Festival, and regional gardening clubs.

Though plants and horticulture remained a passion, Whittlesey’s growing awareness of place, and the way in which plants and gardens fit into the larger environment, became as paramount as the beauty and interest of the plants themselves.

In 2006, Whittlesey completed a certificate program at the California School of Garden Design in Auburn, California, where he subsequently consulted as an instructor. His resulting design work focused on incorporating a diversity of native and water-wise plants—often of his own growing—into habitats that encouraged resource conservation and welcomed pollinators and other wildlife—as well as humans.

While his design career is still young, Whittlesey’s gardens now span the breadth of the northern Sacramento Valley. From small suburban homes to large rural estates, his signatures are a touch of formality, sinuous curving paths, artfully placed rocks (primarily found on or around a garden’s site), and dynamic combinations of his well-loved plants: Salvia, Nepeta, Ceanothus, Agastache, Eriogonum, Mondardella, Zauschenaria, and native California bunch grasses such as Muhlenbergia. His textural plantings flow, pool, and repeat rhythmically—the way you might see them spreading across high mountain meadows or valley grasslands.

Whittlesey’s experience working in the hot, summer-dry climate of Canyon Creek, with only a spring-fed water supply, has proven invaluable in his design work, making him acutely aware of water as a precious, faltering resource. Using it respectfully has become a matter of principle and pragmatism. How to lay irrigation, program it, and monitor it are all of critical importance to his native and mediterranean-climate garden schemes. To add sound and movement, at the same time attracting birds, pollinators, and people, Whittlesy commonly incorporates understated water features of his own design and construction, including small birdbaths and fountains that drip or seep rather than gush.

Water-Wise Garden Design and Greywater Systems

In the early summer of 2010, Whittlesey took the next step on his journey, receiving certification as a greywater systems installer through an intensive hands-on course offered by Greywater Action based in Petaluma, California. Whittlesey wrote of the experience:

The course was excellent and thorough, taught by people extremely knowledgeable about greywater systems and passionate about water conservation. In 2009, California updated its greywater codes to encourage water conservation by facilitating the reuse of water, allowing for simple home-to-landscape greywater systems, as well as more complex systems that require permits. This was a big step forward in allowing individuals to have more control over their water use. Using greywater for irrigation helps conserve water, but it also reduces flows into resource-intensive water treatment plants and closes the energy cycle on home properties. Water and nutrients are kept on site to slowly filter into the soil.

After working on his first few greywater system designs and installations, Whittlesey enthused: “Cheers to greywater running out under a rose bush or a lemon tree. How satisfying to hear a washing machine and know the water is being sent to the garden.” With a greywater laundry system, more thought can, and should, go into the amount of water available and needed, where the water ends up, and how it can be calibrated across the garden, as well as across the lifetime of a garden’s plantings (edibles versus ornamentals, dry-land plants versus moisture-loving ones). Closing the energy cycle is another circle for Whittlesey to explore.

Over the past thirty years, Whittlesey’s educational journey, and the journey of home gardeners—many of whom he has interacted with—has been one of “gardening with more awareness—not simply by default.” It has been a journey, he elaborates, “of waking up to and advocating for the climate and habitats in which we live as gardeners.” We are moving away from being merely plant producers, consumers, and collectors into a more promising role as standard bearers and protectors of one of the world’s most interesting natural gardens—the American West.

In his nursery selections and in sharing his insights with others, Whittlesey has led by example rather than by sermonizing. He is an informed, active, and iconic figure in the broader world of horticulture, as well as in the horticultural communities of Northern California. His gaze is thoughtful as he considers a philosophical question, a planting combination, an irrigation puzzle, or a magical landscape. He still grows plenty of violets and other specialty perennials, but now primarily for his own design work. He’s equally busy leading hikes, hosting workshops, and inspiring others to embrace native plants, habitat gardening, and creative and adaptive water conservation strategies.

His continues to be an educational journey for us all.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses