The Allure of Forest Gardens

Contributor

- Topics: Growing for Biodiversity

Spring 2022

Bravery in a land of lawn and roses

Mark, wearing a T-shirt printed with cats on a galactic background, describes his vision to transform his very traditional lawn-and-roses yard into a forest.

He gestures to the west. “There’s a river not far that way, so I imagine this must have flooded at some time. All the good soil in the Willamette Valley came from flooding.” We talk about what would be growing here if it weren’t a neighborhood of streets and lawns and nursery-grown trees propagated from far-off lands. We share our love of the Pacific Northwest, the most beautiful place on Earth, with ferns and towering bigleaf maples, “and why would you plant anything else?” he wonders.

It’s a courageous vision, not to mold the land to human purposes but to see the natural setting and to respond in relation to it. Though he and his wife Marcy appreciate the quality of the weekly lawn service that they’ve used since moving to their new home, they would prefer a yard that required only seasonal tending. Not because they don’t appreciate maintenance and the value it brings, but because they appreciate naturalness more.

The adjective “foresty” comes up over and over in our conversation. For them, walking out the door into a serene scene requires a forest garden. They could have bought a house in the South Hills, one with an intact forest, and had nothing to do to the yard. But the South Hills come not only with trees but with steep, inaccessible walkways and two-story homes that just don’t work for Marcy’s wheelchair. And so, the bold move to reclaim this very traditional suburban yard as a forest begins.

Imagine a forest

Upon entering a forest you remove yourself from the dailiness of the built environment in which you live and work. Overhead limbs offer primordial shelter. Imagine a forest: cool on a green-filtered summer day, musky in fall with the petrichor of first rains, enclosing and safe through winter’s darkness, young and vibrant even before spring equinox in the mild Northwest. With spring emerges Pacific waterleaf (Hydrophyllum tenuipes) and osoberry (Oemleria cerasiformis), shoots of Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum) and unfurling fern fronds. Branches filter the immensity of sky, the vastness of space laced in green fingers. It’s soft underfoot with duff, the debris of generations collected to cushion, to nurture, to feed the present.

Now, imagine this majesty right out your open door. To plant a bit of forest in a small urban yard is an audacious move toward peace. It says that you value life, more-than-human life. It says that you believe in the future, that you’re patient, that you allow the pace of a tree’s growth to be steady and gradual, enduring longer than your one human life, and for more than your one human life—for birds, and insects, for clean air and water, for climate stability, for the spirit of place.

What is a forest garden?

A forest garden, no matter how small, can be an opportunity to create a garden architecture that invites you to stay awhile. There can be many ways to wander through the trees and even more places to sit. If you watch a frisky dog in a forest garden, you quickly see that it’s not a lawn that makes these quadrupeds happiest, it’s a circuit of looping paths with variation and banked corners and sunny pockets to rest close to the fragrant earth.

The human animal also enjoys a meandering exploration. Unnecessarily winding paths are ubiquitous with amateur garden design. A contrived twist in an entry path when bordering nothing but lawn is silly and really doesn’t relate to anything at all—not to the land and not to the natural way one would walk it. But through a grove of incense-cedar (Calocedrus decurrens) or around a venerable oak, to wind and wend and meander has meaning and gives depth to the experience of the stroll. Before you lay out this type of curving path, place the trees. Let your mind stroll through and under and amidst them in all the possible ways. Be the dog. Be the deer. Be the bird, letting your mind soar from limb to limb. Let your body curve around trunks, fingertips fondling bark, smelling sap.

A forest garden is sensual in profoundly different ways than a food garden. It plays with light and shadow, patterning your sight with depth and dazzle. It crunches underfoot and smells of pitch rather than the tang of tomato or the sugar of berry. A forest garden demands nothing of you and very little to maintain, but still offers a bounty of nourishment. It feeds your soul and your need to be with the more-than-human. Jenny Odell, in her book How to Do Nothing, writes, “it may only be among the most elaborate web of the nonhuman that we can most fully experience our own humanity.” Sitting or strolling amidst the trees is the exact kind of “nothing” that gives balance and perspective to your days of hustle and productivity.

Most of my landscape design clients ask for a reduced or completely transformed lawn. Information on how to get rid of your lawn references meadow or low groundcovers—lovely flowering swaths full of native bees, or easy-care mats of weed-suppressing greenery. What if we reframe the space completely? What if we envision a forest?

How to design a forest garden

If this is truly what your land wants to be, and what you, too, come to want in resonance with the place, then where do you start? Jenny Odell again, “Context is what appears when you hold your attention open for long enough; the longer you hold it, the more context appears.”

Learn the histories and the ecologies of the larger landscape and ask: what trees would grow here naturally? Who else lives with these trees? What’s the understory? What’s the ground floor? Wander in remnant wild places in winter, in spring, in summer, and in fall. See where your yard is similar, where it’s different, and what makes sense to repeat from the wild onto the land you tend. Look at well researched atlases like the Atlas of Oregon. Look at native plant nurseries and, if quite urban, seek out street tree approved lists [pdf].

When you think of a forest, you first think of the trees. We call it a Douglas-fir forest or an oak woodland, a maple slough, or an alder glen. When you start to look closer, you see the layers, the community.

Designing a forest garden requires you to include the community. Planting one tree in a circle of lawn does not a forest garden make. Planting a little grove with a mix of shrubs and some ferns and spring ephemerals, adding a path, a bench, a recirculating fountain—now you have a forest garden.

What if your yard is tiny? What if it’s urban? Can you still have your own little place to forest bathe? Yes, the Dutch garden designer Arjan Boekel has made many small woodland gardens, even on rooftops. Here in the Pacific Northwest, our beloved vine maple (Acer circinatum) fits in the smaller garden to create a leafy bower. Lining a path, the limbs naturally arch overhead for that sacred enclosure and embrace we crave from a forest. Blue elderberry (Sambucus caerulea), chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), and saskatoon (Amelanchier alnifolia) are other natives that can be used in a small yard for overhead shelter. Garden stalwarts like Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonica) and flowering cherries (I adore the cultivar Prunus x yedoensis ‘Akebono’ for its horizontal grace) create a forest garden too, but only when used in multiples or in a community. A forest is not a place of specimens, rather of relationships.

Forest garden case studies

Right: Willamette Valley ponderosa pines (Pines Ponderosa var. willamettensis) launch Stacy’s new community. They lead the way, defining the group to be drought tolerant and habitat rich. Photo credit: Leslie Davis

Stacy’s front yard, like so many, was dominated by lawn. One big Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) anchored the area near the street and inspired a deep border planted as a layered forest. The intention was to embrace her yard with life and to provide her with some privacy from the boisterous neighbors across the street. We placed two Willamette Valley Ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa var. willamettensis) to round the corner. They’ll grow resiliently through our increasingly dry summers that have been slowly killing off Doug-firs throughout the valley.

The midstory includes brilliant winter stems of Pacific Fire vine maple (Acer circinatum ‘Pacific Fire’) and, one of my favorite garden shrubs, Pink Dawn viburnum (Viburnum x bodnantense ‘Pink Dawn’). For year-round screening and to create enclosure and backdrop in the lower layers, we planted a pattern of large growing evergreens, including native Pacific wax myrtle (Morella californica) and variegated silverberry (Eleagnus x ebbingei ‘Gilt Edge’). Shade-tolerant ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor), and upright Lewis’s mock orange (Philadelphus lewisii) stand near the trunk of the venerable old Doug-fir. Then, a red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) steps forward, coloring the early spring sunshine closer to the lawn clearing.

As a chest-high groundcover around the trees and large shrubs, we planted snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), and, one layer down, creeping mahonia (Mahonia repens) in blocks, mimicking the spreading masses that grow in wild woodlands. A woodchip path curves through the wide bed, with another path of steppingstones leading to a contemplative bench. With this framework in place, Stacy has added perennials over time, layering the forest floor with seasonal blooms. What was lawn and an exposed front yard is now a lap of life, a sanctuary, an ecosystem.

When I met Menina and Josh, their small front yard was an unorganized scene with a few great plants, namely a flowering cherry (Prunus sp.), a saucer magnolia (Magnolia soulangeana), and a wonderful old lacecap hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla cv.). The two small deciduous trees set the stage for an inspired forest garden. The big moves we made that brought it into harmony included: editing out an overly large rhododendron that was darkly brooding near the front door; reducing the lawn in favor of deeper beds and a smaller, circular lawn evocative of a woodland opening; and layering the midstory and ground plane with plants for all seasons.

A Butterfly Japanese maple (Acer palmatum ‘Butterfly’) now glows brightly in the corner where once the rhodie loomed. Its grace calls up memories of walking a forest trail with the added sparkle of ever-changing foliage color. Dwarf rhododendrons (Rhododendron sp.) with felted leaves and starry flowers mingle with the fine textures of black mondo grass (Ophiopogon planiscapus nigrescens) and the bold saucer leaves of hosta (Hosta ‘Sum and Substance’). Hardy ground orchids (Bletilla striata) circle the magnolia tree while tall native goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) stands on the sunny edge of the garden, feeding late summer daydreams and pollinators alike. A large variety of plants—from strawberry begonia (Saxifraga stolonifera) and golden dead nettle (Lamium maculatum ‘Aureum’) in the shade, to kinnikinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) in the sun—cover every inch of bare ground just as you would see in any wild Northwest forest. Using the ecological patterns of forest to redesign this garden led to a solution that Menina and Josh love to come home to every day—a place where they can putter or simply sit and relax, watching the light filter through the leaves overhead.

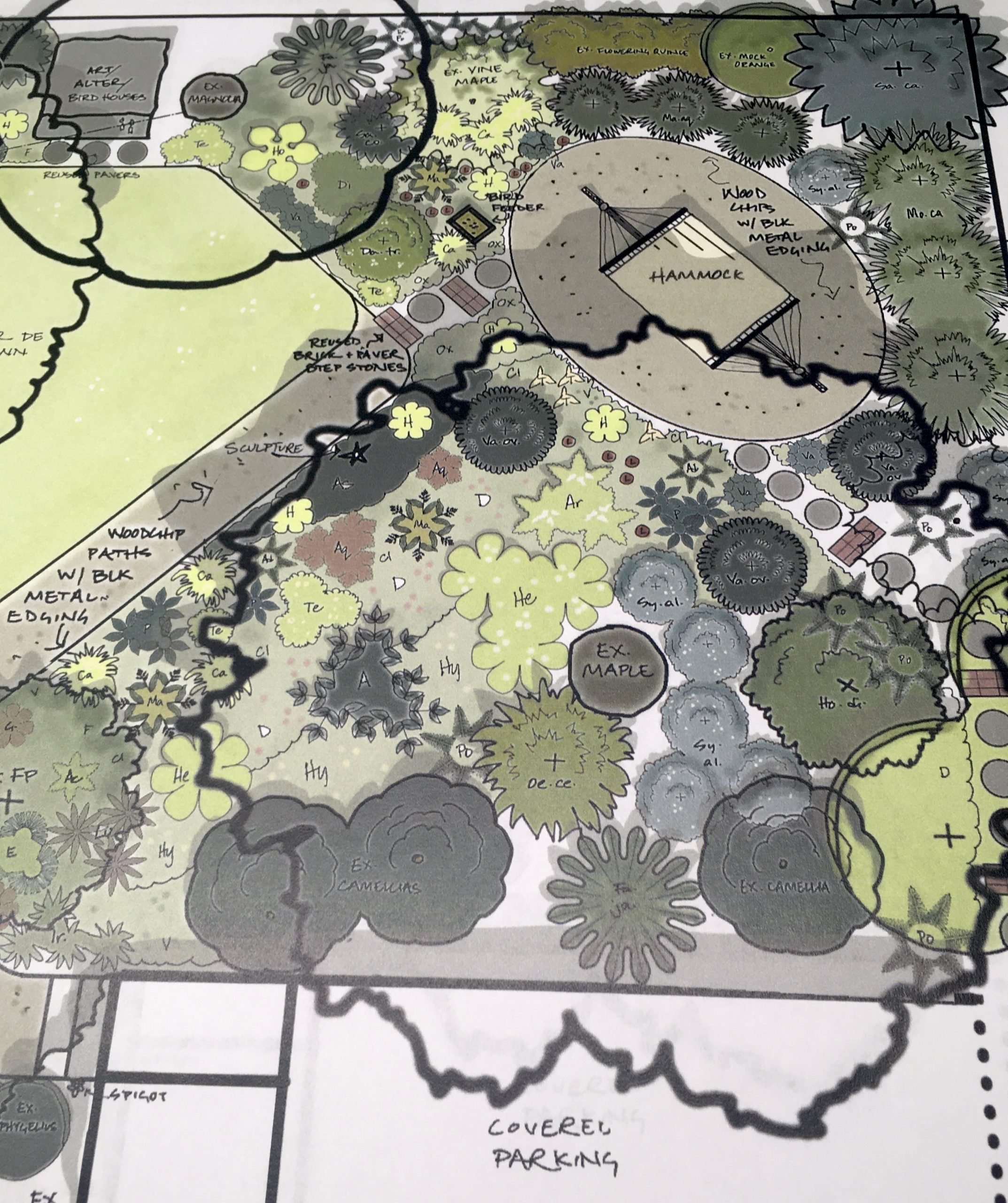

I like to imagine entering Julie’s garden through the alley gate. This is where the mystery unfolds, the transition from utility to rest, the threshold experience. Say you drive home from your life of activity, engaging meaningfully with the world, tapping your well of available attention. You’re depleted. It was another long day. You pull into the carport from the alley, plug in your electric vehicle to recharge for the night, and then, instead of hustling via the direct path indoors, let yourself detour through the gate into the forest garden for your own recharge. Immediately, the slender verticals of chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) embrace you—an initiation of sorts back into the realm of trees. Venturing along the varied steppingstones (brick clusters, mossy circles—all reused from an earlier, mid-century version of the garden), you pass under the ancient, muscular limbs of the Crimson King maple (Acer platanoides ‘Crimson King’) and brush your fingertips against the delicate leaves of snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus). A small, oval opening of soft-underfoot wood chips beckons with a hammock. Set your parcels and the stress of the day down. Let your body lay and lengthen as you gaze skyward, swaying. Bushtits and wrens, nuthatches and sparrows, all of your familiar feathered friends sing from safe perches encircling you. This is the therapeutic magic of a forest garden. To create this experience for Julie, I designed the rear section of her backyard as an enclosure of understory species including an existing lilac (Syringa vulgaris), a blue elderberry (Sambucus caerulea), a few Pacific wax myrtle (Morella californica), vine maples (Acer circinatum), and Lewis’s mock orange (Philadelphus lewisii). This hammock-centered forest garden will come to life this summer!

Conclusion

If it’s true that we as a species became upright bipeds only once we left the woodlands for the wide-open savannas, then what does this craving to return to the forest signify? Why do people like Mark and Marcy want to transform their lawn-and-roses yards into forest gardens? A reconnection to ancient ancestral views of vertical trunks and fractal branching is deeply soothing. Wide open lawns aren’t used for running down game. They no longer serve the purpose of hunting grounds. Modern expanses of lawn now mean two-stroke engines, weekends consumed by chores, loss of biodiversity, and a preference for staying indoors when you seek privacy. A forest garden can offer you solace, retreat, birdsong, patterned light and shade, and a rooted sense of place.

“This rootedness is something we desperately need when we find ourselves awash in an amnesiac present and the chain store aesthetic of the virtual,” Jenny Odell writes.

Whether you’re motivated to plant a forest garden to capture carbon for climate mitigation or for more spiritual reasons of respite and relaxation, remember that a forest is more than its trees. Plant all the layers from high canopy down to flowering forest floor to re-create the complexity and dynamic stability of a wild woodland.

Resources:

Many urban communities, such as Eugene, Oregon [pdf] offer approved street tree lists.

Loy, William G. 2001. Atlas of Oregon. 2nd ed. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

Odell, Jenny. 2019. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Brooklyn: Melville House.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Responses