Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Hidden away in an evergreen woodland, behind a maze of 12-foot-high security fences topped with razor wire, where few might expect to find any good, lies a garden chock-full of life and color.

The men who tend this garden—soldier prisoners under incarceration for violating military law—take deep pride in raising quality fruits and vegetables from its soil. They await the day when they’ll return to the world outside their enclosed perimeter, but until then, they find solace in their own personal 22- by 26-foot plots that produce corn, green beans, peas, hot peppers, cucumbers, squash, cabbage, cherry tomatoes, mushrooms, watermelon, strawberries, and more. Crops good enough for commercial produce stands.

“See?” one of them boasts striding toward his fellow inmates on a recent morning, holding high a plump Spanish onion he’s just pulled from his garden.

“That’s a nice one!” says Charles Kentfield Jr., who, for the past two years, has taken prisoners at the Northwest Joint Regional Correctional Facility on Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), under his wing to study gardening and farming. “That’s a gem!” he says. “You could eat that and it would be sweet like an apple.”

Kentfield, who works for Clover Park Technical College in Lakewood, Washington, leads the prison’s horticulture program where, each weekday, he teaches and encourages a small group of prisoners to harness their inner green thumb.

The training—nothing like any Army training these men have ever had—is just one of a small handful of vocational programs, including carpentry and working in the facility’s barber shop, offered by the jail. Participants are carefully selected for the horticulture program based on previous offenses and whether they’ve displayed violence at any point in time. According to JBLM staff, inmates in Kentfield’s group have the least disciplinary issues of the nearly 125 service members at the prison.

The program began with little more than two empty greenhouses—a dismal sight for any green thumb. Classes were held in the prison’s carpentry shop, or its chapel when there wasn’t room in the shop. “We didn’t have anywhere to call home,” he said. “When you’re trying to build a team atmosphere, you’ve got to have your own space.” So the group set out to make a place of its own. Kentfield taught his students to pour concrete, lay stone pathways, and construct irrigation systems for the buildings.

Instruction consists of a yearlong curriculum during which the inmates earn 11 credits while learning about small farming equipment, diesel engines, landscape construction, nursery management, and plant propagation and identification. The men learn to properly sharpen gardening tools, to use chainsaws, tillers, and tractors, and even pick up a little business.

The group comes out to the garden first thing in the morning and spends at least seven hours with Kentfield. “I try to make it as real as college can possibly be,” said Kentfield, who designed the curriculum with staff from Clover Park. “I expect a lot out of them.”

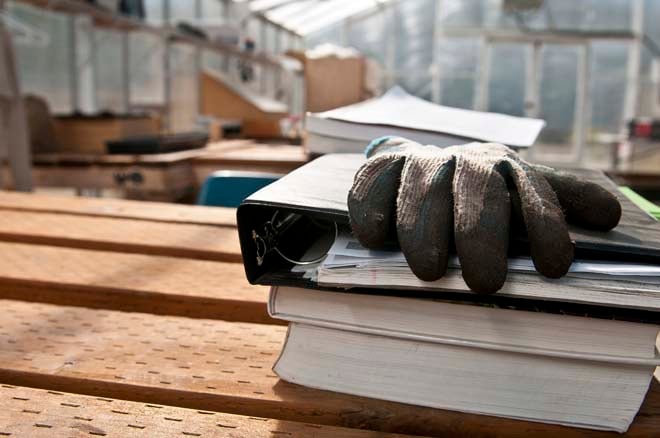

These days, the renovated greenhouses are full—one with desks, chairs, textbooks, work gloves, and notebooks, and the other with a variety of plants and flowers. “Is this the best use for a greenhouse?” Kentfield said admiring the inside of the greenhouse the group uses as a classroom. “No. But it’s ours.”

Outside, inmates grow their own produce in one of 15 plots. Across the yard, an area that appears to be nothing more than tall dry grass along a fence line is actually a seed farm raising seed stock of Northwest prairie plants for the Department of Public Works to plant to restore training areas and ranges on JBLM where military vehicles and artillery have destroyed the landscape.

Last year, Kentfield and his students began providing vegetables to the Thurston County Food Bank in nearby Olympia, Washington. Twice each week, the prisoners proudly pull, wash, and package their best vegetables from their plots. Within two hours, the freshly harvested produce is on the shelves of the local food bank, ready for families to take their pick.

“That’s what you did with your family garden when you had extra, you loaded it up in the car and took it down to the food bank,” said Kentfield, who packs the vegetables into the trunk of his sedan and personally delivers the fresh produce.

Kentfield’s garden, filled with towering corn, colorful wild flowers, and neat rows of healthy crops, is a flourishing testament to the lessons he has taught his students, not only in agriculture, but also in life.

“You have to grow from seed, to start, to maturity—not just in plants and ideas, but in every aspect of your life,” a prisoner who has participated in the program for the past 15 months said in a written statement. “That is the true gift every student takes away from this program,” he said. “A chance at a clean slate, an open ear to listen, and new insights on all of life’s problems.”

“I try to stress being a good person—trusting that if you do good things, good things will come back to you,” said Kentfield, whose biggest concern is ensuring inmates have strong resumes upon their release. “It’s simple living. I guess that’s the best way to say it. Being a good person, living simply, being happy.

“I want it to be like it is on the outside for them; I want them to be accountable for what goes on, and understand what professionalism really is.”

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Healing Gardens

Spring 2022 Emily Murphy believes gardens hold the key to saving our health, our communities, and our planet. In her new book Grow Now Murphy

Your Keystone Plant Matrix with Garden Futurist Doug Tallamy

Spring 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XIV podcast here. If you take Keystone plants out of your local food web, the food

A Botanical Force

Listening to Alice Doyle recount the origin stories of Log House Plants’ most popular introductions, educational campaigns, and innovative collections is a great way to

Responses