Contributor

That the architects, Kevin Roche and John Dinkerloo, should have chosen to create an urban park rather than a massive structure is in itself remarkable in this age of mammoth monuments and skyscrapers.

Geraldine Knight Scott

The roof gardens of the Oakland Museum were planted in 1967 and 1968, and the horticultural successes and failures are now being assessed with an eye to the future. The overall design, the soil mix, the plant selection, and the maintenance plan are being carefully reviewed to incorporate into a renewal plan the experience of the past twenty-three years. Little has been changed since the initial planting, and consequently, the Oakland Museum is one of few situations where the long-term effects of container gardening can be seen.

Everything about the Oakland Museum was new and innovative at the time it was constructed. Art, history, and science function as separate departments but are all within one building. Architecturally, it departed from the traditional concept of the museum as monument. The site is four city blocks at the southern end of Lake Merritt adjacent to the Alameda County Courthouse and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center. Here architect Kevin Roche chose to create a civic space over and around the museum galleries and services — an extension of Lakeside Park on the north that would link the public buildings in the area. The gardens, he explained, would “allow one to walk over the entire thing, down to a lagoon, up and down a step, under arbors of blossoming vines.”

The roof gardens were to be more than the top of the building. They were to be the building itself, and, as the design progressed, Roche brought in landscape architect Dan Kiley to help define the gardens. Kiley, whose office is on the shores of Lake Champlain in northern Vermont, called on Geraldine Knight Scott, a Berkeley landscape architect, for help with plant selection in the climate of the San Francisco Bay Area. Taking their cue from the large deodars, Atlas cedars, and redwoods already established at the east end of the site near the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center, the design team decided on a scheme with a tall screen of trees around the perimeter, regular rows of smaller trees marking the elevations within the complex, and an irregular undergrowth of shrubs and vines.

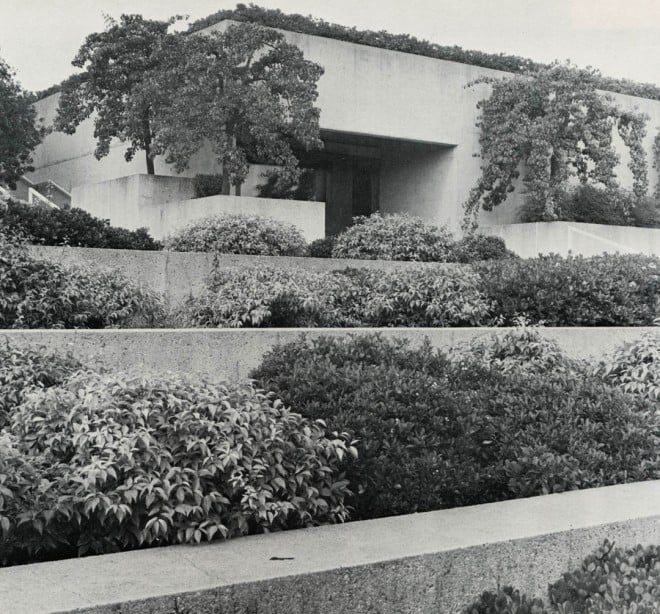

The size of the project is formidable: almost seven and three-quarter acres, and 26,400 square feet of planting beds. They hoped that the place would quickly acquire the look of an old and overgrown villa with vines and shrubs cascading over rectilinear concrete terraces. Kiley has explained that “the plants become a lacy veil superimposed on the surface to complement and soften this rigid geometry of structure.”

Other design decisions included the use of evergreen plants throughout, primary colors for flowers, and fragrant plants along the principal walkways. Evergreens offered three advantages: maintenance would be easier, the roof would never have a barren look, and there was less chance of leaves clogging drains. The only exceptions are a group of three liquidambars in the courtyard lawn, which provide dramatic fall color, and some white alders (Alnus rhombifolia). Broad areas of red, yellow, and blue flowers are also intensely colorful, and at the same time produce the seasonal variation so often absent in an evergreen garden. Trumpet vine augmenting the color, and gardenias, honeysuckle, and rosemary for fragrance, have been the most successful plants along the outdoor corridors.

Roof garden technology was less well developed in the 1960s than now, and there was little information available on the growth and long-term requirements of masses of plants in containers. The three greatest concerns at the time were the weight of gardens over structures, the shallow depth of beds (twelve to thirty-six inches), and the drainage system. The gardens were to differ quite markedly from that of the nearby Kaiser Center roof garden of the early 1960s. There trees and shrubs are buried in individual containers, making replacement of problem plants a simple matter. Although the need to support soil, water, and mature plants was taken into account by the architects and structural engineers early in the design process, their weight is still a concern when considering new soil mixes or additional paths through planter beds. Shallow beds meant that root-bound plants were inevitable, and twenty years later maintenance engineers are amazed at the size and length of the roots invading the drainage system.

The soil mix for the planter beds was critical to the success of the roof gardens. A soil specialist from the University of California Soil and Plant Laboratory in Hayward recommended two well tested mixes that would meet the needs of different plant groups. The basic mix for general planting was composed of redwood sawdust, sand, blood meal, super-phosphate, potash, ground oyster shell, dolomite lime, and ferrous sulphate. The more acidic mix for the beds with azaleas, ferns, and other plants with similar needs combined peat moss and fir bark with lesser quantities of blood meal, super-phosphate, ground oyster shell, and dolomite lime. A layer of sand covered plastic drains at the bottom of each bed to remove surplus water. Ordinary topsoil was used in the beds not over structures. Liquid fertilizer, high in nitrogen (14-4-4), is injected regularly through the irrigation system, assuring an even supply of nutrients in the spring and autumn. This has been successful and virtually problem-free.

By 1977, ten years after installation, the soil level had dropped significantly in the containers. In 1985 the soil levels were down further, and the organic matter was nearly gone. By 1990 the soil was reduced by one-third to one-half in areas to which supplemental organics had not been added, and as the trees sink along with the soil, the biggest problem will be how to raise them again. Specialists are questioning the long-term viability of soil mixes that require constant renewal.

Covering the entire roof with plants in time for the museum’s opening in 1970 was accomplished with groundcovers, which formed the base planting of each bed, under slower-growing shrubs and trees. The original groundcovers included abelia, ajuga, ceanothus, wild strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis), ivies, Hypericum calycinum, juniper, ice plant, lantana, rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Lockwood de Forest’ ), star jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides), Vinca minor, and dichondra. The quantities were staggering: over 35,000 plants of ivy, over 25,000 of wild strawberry, 18,000 of ajuga, and so on. None are rare, unusual, or difficult to grow under local conditions. This was true of nearly all the plants selected for the site. The shallow beds, synthetic growing medium, artificial drainage, and vast scale with huge quantities of plants provided sufficient challenges without adding plants that would need constant attention.

The groundcovers flourished in the early years, covered the roof for the opening, and tumbled over the walls, softening the rigid lines of sandblasted concrete. Some, such as the rosemary, grew at a remarkable rate and formed curtains nearly across the main walk, an effect far more striking than anticipated. At the same time the groundcovers were the most susceptible to trampling and, in general, are the plants that need replacing most frequently. Ceanothus, for example, is notoriously short-lived, especially when over-watered, and none of the original plants survived nor have they been replaced. Dichondra, too, turned out to be unreliable in this situation. Rosemary, although surviving, is now woody and not as attractive as when young plants billowed over the balconies. The ivies thrive, but frequently cover and choke out other plants.

The perimeter of the building is defined by the old cedars and redwoods on the east end, and the screen of tall trees was continued with eighty shallow-rooted ironbark (Eucalyptus sideroxylon) planted along the south, west, and north sides of the building. This eucalypt was selected because it is tolerant of automobile exhaust, does not shed its bark, and has blue-green leaves that turn bronze in the winter, giving seasonal variety. The established cedars and redwoods have had few problems, requiring only occasional pruning and thinning. The eucalypts, however, have been less reliable: roots cracked concrete walls, branches broke in storms, trees blew over, and others died sooner than expected. Australian tea trees (leptospermum laevigatum), common throughout Oakland parks, were planted behind the eucalypts along the outside terraces, and these have grown exceptionally well. They are longer-lived than eucalypts and survive these conditions, including wind and sun reflected off concrete. Their mature shape, however, is twisted and gnarled, so that, while picturesque, they do not form a high screen along the streets surrounding the building.

Within the walls three levels of galleries step down and open onto a central lawn. The windows on each level look out through double rows of evergreen pears (Pyrus kawakamii) pruned into weeping shapes. Underplantings have varied, including bergenia, nandina, rosemary, and the few Natal plums (Carissa macrocarpa) that survived the severe freeze in December 1972. Even though soil levels have dropped nearly twelve inches and the pears are rootbound, all sixty-four have fared remarkably well, and a life span of twenty-five to thirty years in these conditions is a reasonable expectation.

Other medium-sized trees used to mark terraces include strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), olive, and Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica ‘Glauca’). The strawberry and olive trees are all on the topmost level, above the galleries, and are underplanted with dwarf myrtle (Myrtus communis ‘Compacta’). The strawberry trees have suffered from the diminished soil, but the olives, long-lived and needing little soil or water, are thriving under conditions that strain most of the other plants. The myrtle, too, is growing well under difficult conditions, and now competes in size with the trees.

Thirty-five Atlas cedars around the interior courtyard surprised everyone with their rapid growth: in ten years they appeared twice their age and had crowded out the azaleas planted among them. After twenty years they required major pruning and thinning, and they now completely cover the planters. The rapid growth of the cedars has been attributed to the high organic content of the artificial soil mix used for these beds.

Heavy redwood trellises rim part of the interior court and shade the entrance walkways. The trellises were to carry a variety of flowering vines, principally deep red bougainvilleas, which would filter warm light through their translucent bracts. Unfortunately, the 381 tender bougainvilleas were not well enough established to withstand the devastating freeze in 1972. Trumpet vine (Campsis grandiflora) and the giant Burmese honeysuckle (Lonicera hildebrandiana) have both thrived. Creeping fig (Ficus pumila), which is combined with groups of ferns in dark areas along an entrance walk, has also been effective in softening the hard concrete and appears lush even at the driest times in summer.

The original design provided for the possibility of a hundred-year storm and consequent heavy water runoff, but water rationing in successive drought years has presented unexpected problems. Before the 1977 rationing Mrs Scott recommended removing groundcover under trees, overgrown shrubs, and some tree ferns in an effort to save the larger plants. She also suggested a mulch to reduce evaporation and conserve soil moisture. These and other suggestions were never fully implemented, but groundcover and shrubs under large trees have not been replaced where they have died. By the end of the 1990 dry season many plants were under serious stress, most notably those that are severely rootbound and those near the end of their normal life span.

The concepts behind Roche, Kiley, and Scott’s design have proved sound, and the Oakland Museum has, without question, one of the most extensive and dramatic series of roof gardens to be found anywhere; they virtually camouflage the massive building. Despite the difficulties of age, the gardens remain handsome and a delightful refuge from city streets and unfriendly buildings. The gardens have also been an extraordinary experiment in container gardening. Unfortunately, the artificial soil in shallow containers has accelerated the natural cycle of growth, maturity, and decay, and the desired effect of the old and overgrown villa is giving way to the less attractive aspect of an incipient ruin in many areas. Only with renewal will the cycle begin again. In retrospect, the most important lesson from the roof gardens at the Oakland Museum is the importance of ongoing horticultural consultation to facilitate the renewal and replacement of soil and plants on a regular basis.

Responses