Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Sustainable Gardening

[sidebar] You’re invited to an Open Garden Event at the Gottlieb Native Garden on March 18, 2018. Go HERE to register. [/sidebar]

What defines a native plant? This is a contentious subject. Some botanists and biologists believe that once a species has been in North America long enough it effectively becomes native. But that’s not really true, according to wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy and others. Our human perception of a “long time” is minuscule compared to the incomprehensible scope of evolution. Because plants and animals in an area coevolve, a plant can function as a true native only if it helped shape the community historically. So while some would argue that a plant native to a similar climate zone in another state is native in Southern California, this belief fails to take into account the needs of local wildlife and the realities of ecology. Just because plants can thrive in our mediterranean climate and can help to conserve water doesn’t mean we should plant them if few native insects can use them for food.

What defines a native plant? This is a contentious subject. Some botanists and biologists believe that once a species has been in North America long enough it effectively becomes native. But that’s not really true, according to wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy and others. Our human perception of a “long time” is minuscule compared to the incomprehensible scope of evolution. Because plants and animals in an area coevolve, a plant can function as a true native only if it helped shape the community historically. So while some would argue that a plant native to a similar climate zone in another state is native in Southern California, this belief fails to take into account the needs of local wildlife and the realities of ecology. Just because plants can thrive in our mediterranean climate and can help to conserve water doesn’t mean we should plant them if few native insects can use them for food.

What defines a native plant? This is a contentious subject. Some botanists and biologists believe that once a species has been in North America long enough it effectively becomes native. But that’s not really true, according to wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy and others. Our human perception of a “long time” is minuscule compared to the incomprehensible scope of evolution. Because plants and animals in an area coevolve, a plant can function as a true native only if it helped shape the community historically. So while some would argue that a plant native to a similar climate zone in another state is native in Southern California, this belief fails to take into account the needs of local wildlife and the realities of ecology. Just because plants can thrive in our mediterranean climate and can help to conserve water doesn’t mean we should plant them if few native insects can use them for food.

What defines a native plant? This is a contentious subject. Some botanists and biologists believe that once a species has been in North America long enough it effectively becomes native. But that’s not really true, according to wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy and others. Our human perception of a “long time” is minuscule compared to the incomprehensible scope of evolution. Because plants and animals in an area coevolve, a plant can function as a true native only if it helped shape the community historically. So while some would argue that a plant native to a similar climate zone in another state is native in Southern California, this belief fails to take into account the needs of local wildlife and the realities of ecology. Just because plants can thrive in our mediterranean climate and can help to conserve water doesn’t mean we should plant them if few native insects can use them for food.

[pullquote]Conservation is a way of showing that you believe in tomorrow.[/pullquote]

Reconciliation ecology is an emerging field that encourages the reintroduction of biological diversity in human-dominated ecosystems. It is a spinoff of “island biogeography,” which emphasizes preserving the biodiversity in wild places rather than figuring out how to create habitat for wildlife in developed areas. Scientists are beginning to understand that if we consider human-dominated areas to be landscapes incapable of supporting wildlife, then we will lose unacceptable amounts of biodiversity. Tallamy posits that “unless we restore native plants to our suburban ecosystems, the future of biodiversity in the U.S. is dim.”

Ecologist Michael Rosenzweig, in his groundbreaking 2003 book Win-Win Ecology: How the Earth’s Species Can Survive in the Midst of Human Enterprise, describes reconciliation ecology as “the science of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species diversity in places where people live, work, or play.” In his view, by using reconciliation ecology as a tool, we might be able to avoid the mass extinction event toward which some scientists say we are hurtling.

A fundamental tenet of reconciliation ecology is that we, as human beings, can have our cake and eat it too. We all love nature, but rare are the people who would wish to sacrifice their homes and their cities to a wilderness unsuitable for modern society. Scientists say we can reconcile our needs with the needs of other creatures.

“We must back off a bit, not on the amount of land we take for ourselves, but on how we transform it for our use,” Rosenzweig says. “Right now, our footprint is too big. It will take a lot of work. But imagine the result: a vast area of diverse anthropogenic habitats that meet nature halfway instead of trampling her underfoot.”

The National Wildlife Federation has a wildlife habitat certification program. Rosenzweig lauds this Backyard Wildlife Habitat campaign as “a beacon for those of us who believe that reconciliation ecology can pervade our home sites.” With each of the 20,000 private patches certified in the last 30 years — like the Gottliebs’ pocket park in Beverly Hills — we’re stepping closer to designing “mosaic cities” that interweave native and wildlife habitats with the built environment.

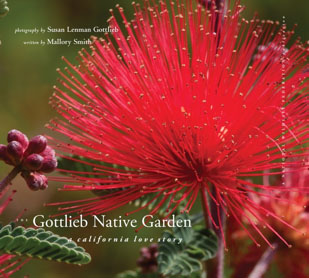

Restoration Ecology and all photos excerpted from The Gottlieb Native Garden: A California Love Story by Mallory Smith, with photography by Susan Lenman Gottlieb. Copyright 2017, National Wildlife Federation. Reprinted with permission by the publisher.

Restoration Ecology and all photos excerpted from The Gottlieb Native Garden: A California Love Story by Mallory Smith, with photography by Susan Lenman Gottlieb. Copyright 2017, National Wildlife Federation. Reprinted with permission by the publisher.

Mallory Smith is a freelance writer and editor specializing in environmental, social justice and healthcare-related communications. She graduated from Stanford University in 2014 with a B.A. in human biology and a concentration in environmental anthropology. Previously, Mallory worked as a senior producer at Green Grid Radio, the environmental storytelling radio show and podcast that aired on KZSU Stanford 90.1 FM in the Bay Area. Her radio work has been featured on NPR’s All Things Considered (for KCRW, LA’s NPR affiliate), National Radio Project, and State of the Human.

Susan Lenman Gottlieb is an environmentalist and philanthropist with a passion for native plants and wildlife. Originally from a small mining town in Canada, Susan graduated from the Mack Training School for Nurses in Ontario before working as a nurse for many years in San Francisco and Los Angeles. In 1990, she turned her focus towards creating the renowned Gottlieb Native Garden, which is now a National Wildlife Federation-certified Backyard Wildlife Habitat and a Xerces Society-designated Pollinator Habitat. Susan is on the President’s Advisory Council for National Wildlife Federation and the Board of Directors of Friends of Ballona Wetlands, as well as Audubon California. In 2008, she and her husband Dan started The G2 Gallery, a nature and wildlife photography gallery in Venice, California that donates all proceeds of art sales to environmental causes.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses