Contributor

- Topics: Archive

The practice of horticulture is often described as a combination of art and science. And the practice of pressing botanical specimens demonstrates this nicely, I think. Every plant species has its own essence, so to speak, and capturing that unique morphological integrity can be very satisfying. To do this, carefully select plants to illustrate as many characteristics as possible; for example, the fine roots of a bunchgrass or the rather stout culms of sedge add a lot to a composition. If possible, it’s nice to collect an extra flower or two to press separately, especially if stems or other plant parts are large and will dry more slowly than the flower.

When creating a composition, I lay the plant out on 11- by 15-inch heavy weight Strathmore watercolor paper, in a way that, to me, presents a classical representation of the species. Coaxing a leaf or twig just so can be done with forceps, pins, or painter’s tape: I tend to use anything at hand. Securing the piece in place with gummed linen tape can either be done at this stage or saved for final presentation on a clean sheet of mounting paper. This very much depends on how large and woody or moist the sample is. Very large specimens are best dried separately and then mounted once completely dry.

Top the botanical specimen with a clean sheet of blank newsprint or drawing paper and sandwich between several sheets of newspaper and two pieces of rigid cardboard. This holds everything in place and allows for air circulation and faster drying, which reduces the possibility of mildew and results in better color retention. At this point, a heavy weight is needed, (bricks, heavy books, a concrete stepping stone) or a plant press that can be cinched tight. A fan speeds the drying process, as does low humidity and warm temperatures (up to 95 degrees or so).

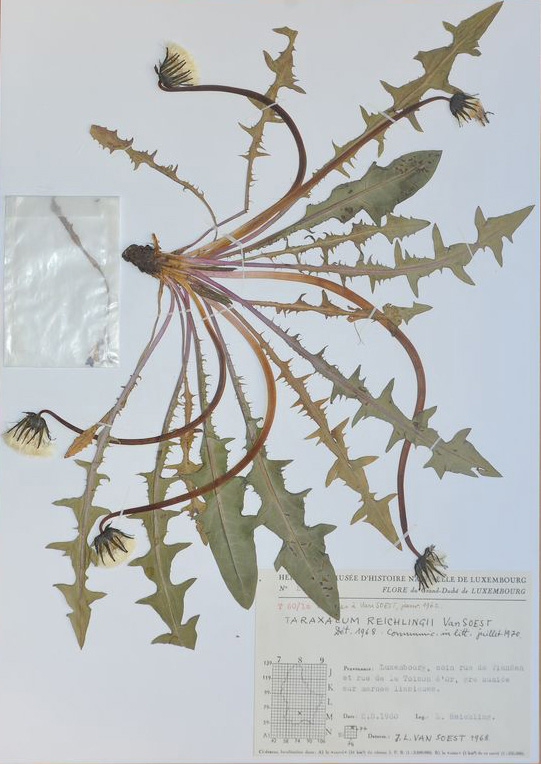

The first rule when collecting wild plants is to gain permission. Collect only a specimen or two, just enough, leaving plenty of plants to grow and thrive. Of course, collecting in your own garden is a fine way to practice the art as well. Even weeds can be beautifully pressed, elegantly shown below with a cousin of our ubiquitous lawn pest, the common dandelion.

Once the specimen is dried and mounted, I like to leave room for an herbarium specimen type of label that includes the plant’s scientific name (genus, species, and infraspecies information), the collection date and location, and the collector’s name. (True botanical voucher specimens require much more detailed information.) The finished piece can be matted and framed for display or stored in a cool dry place; remember that the specimens themselves will be brittle and require careful handling.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses