Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens and Design

Art, which now apparently embraces all forms of self-expression, here suggests new relationships between artist and nature more appropriate to a time when the natural world exists only as vestiges maintained through human intervention.

Gardeners, and writers about gardens, frequently claim that gardens are a form of art. Their reasons are usually aesthetic, involving the discerning use of color, form, and space. Formalist aesthetics can be a rich field of exploration, and gardeners and artists have learned much from each other.

But art has other dimensions. Art-making can be seen as a way of setting forth ideas and conceptions about the world. In this way art can be described as having a text. Much contemporary high art emphasizes this as an area of exploration.

Gardens, too, have texts as well as aesthetics. The garden site conveys ideas about nature, spirituality, and human relations. Moslem gardens, with their crossing “rivers,” “fields” of fruit, and aura of ease, express the Koranic idea of paradise. Renaissance gardens could be intensely allegorical: in the Garden of Love at Villandry in France, clipped boxwood tells the story of romantic love.

The important elements that a gardener works with are generally seen as part of nature. These elements include weather, plant genetics, and soil and light conditions found on the site. Gardeners articulate a set of attitudes and ideas by how they develop these elements — whether exotic plants are imported or natives are used, whether the terrain is altered or the gardener accepts what is already on site, whether plants are painstakingly dead-headed or allowed to follow their own cycles.

Nature becomes a garden at the onset of human intervention. The woodland becomes the woodland garden as soon as a single trillium is tucked in. But what does it mean when vaster tracts of wilderness, the site of nature in its supposedly more pure form, are subjected to massive human intervention in order to save them — for instance, the weeding out of that garden renegade, Cytisus scoparius, from the California chaparral? Is the whole world a high-maintenance garden’?

In Problems in Materialism and Culture, the late Raymond Williams, a prominent British literary critic, maintained that “the idea of nature is the idea of man, the idea of man in society, indeed the ideas of kinds of societies.” In other words, whether one conceptualizes a perennial border or a social system, nature is seen as the teacher, the example, the justification. But then, where does nature end and not-nature begin?

A recent show at Langton Arts Studio in San Francisco answers this question quite simply: We are in an era that is Post Nature. As gallery director Renny Pritikin puts it in his curatorial essay: ”Post Nature is… an attempt to address art’s contemporary relationship to nature. The traditional model of art’s relationship to nature was that art was a bridge between nature and culture, the man-made. Today… nature and art are perceived equally as cultural constructs.”

In assembling installations for the Post Nature exhibition, the world of horticulture was explored in interesting ways for its contribution to the discussion. All of the artists shown practice on the West Coast of the United States, mostly in California.

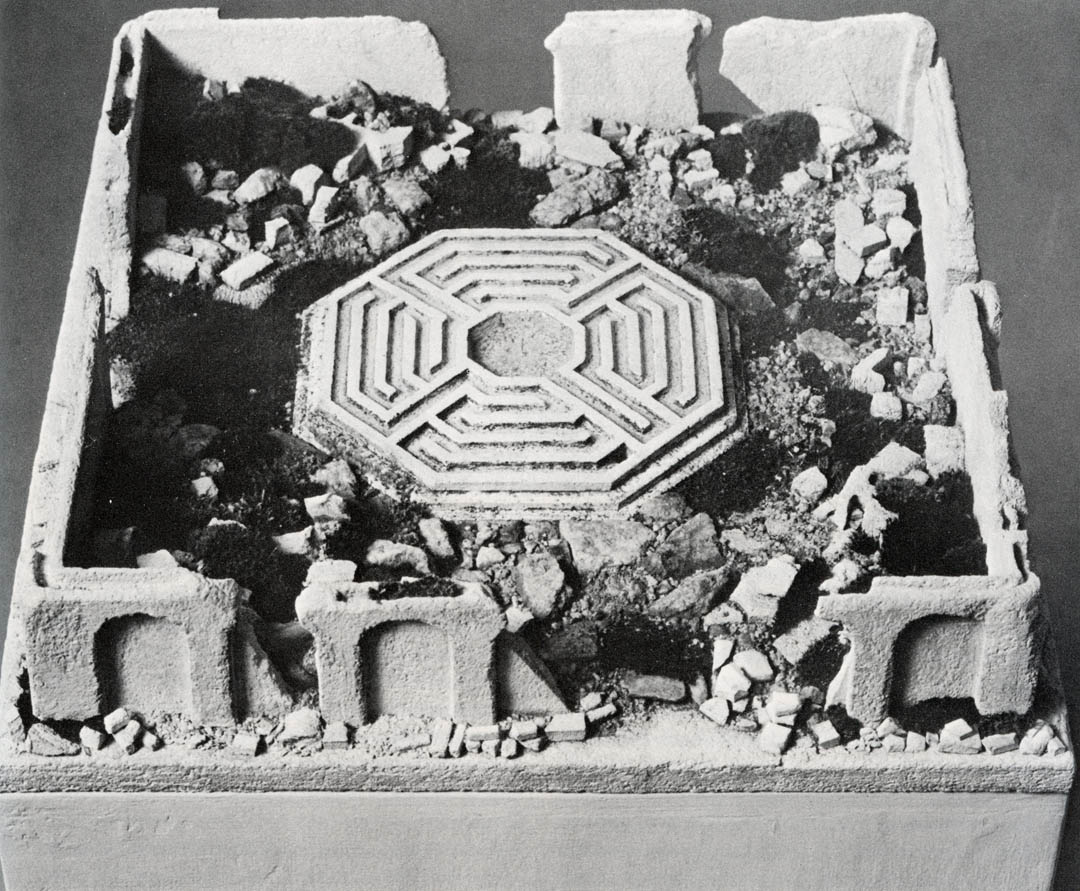

Mary Helen Chappell’s small-scale classic gardens were the first works encountered upon entering the gallery, and they made the gardener feel immediately at home. Chappell comes from the world of horticulture; her first creation, a miniature Elizabethan knot garden featuring bonsai herbs, won first place at the 1983 horticulture and garden show at Filoli. She renders classical garden designs into small-scale, toy-like, dimensions: most of her work is sixteen inches square. Mosses are substituted for shrubbery, wire vine (Muhlenbeckia) for arbor vines. The miniatures are mounted on ceramic bases that are architectonic; their doorways are “bricked” off, denying immediate access to the interiors of the gardens above. Chappell’s gardens, like their larger inspirations, are meant to be appreciated from above. One can sense the time she spends thinking about, and then creating, her objects. Some would say that Chappell’s precious mock-ups of upper-class gardens are created from the standpoint of privilege; I would prefer to say from a longing for Utopia.

The gallery has one large, sunny window, and taking advantage of its light was a collection of Pacific Coast irises, the sculptural work of George Gessert. Gessert uses the DNA of the irises, primarily Iris douglasiana and I. tenax, as a sculptural medium. Currently there is a great deal of interest among cultural critics in the model of DNA, a code that, according to Fredric Jameson, “displaces biology from the physics model to information theory.” Biology is no longer destiny but a computer program to be elaborated, readapted, or debugged. From blue roses to tobacco plants fitted with a firefly gene to make them glow in the dark, plant breeders are engaged in altering genetically inscribed programs.

In his work Gessert tries to point out both the ethics and the aesthetics of this practice. As performance artist Laurie Anderson chants, “Ethics are the aesthetics of the future.” Gessert uses Pacific Coast irises for a couple of reasons. First, they make fertile crosses only among themselves; the offspring of crosses with other species are mules. Second, they “celebrate” the particular climate and soil of the central Oregon bioregion, and thus are an expression of a profound regionalism.

Gessert sees no difference between his breeding activities and those of professional iris growers and hybridizers. Both he and they make aesthetic choices. But professional growers must cater to a mass market, a market whose predominant taste, according to Gessert, is for “mottled foliage, oversized flowers, doubled flowers, and flowers ruffled, crimped, and laced.” Shamelessly drawing on the ideas of modernist critic Clement Greenberg, who would probably sneer at the idea of a sculptor who works in irises, Gessert develops his irises with respect for their characteristic qualities.

The second stage of Gessert’s iris project is to plant the irises in zones where distinctions between domestication and wildness break down — in forests, especially along road banks, but really anywhere Gessert can hike to. His intervention is not irresponsible — the irises are non-invasive; he is simply claiming a role in the workings of his environment. Gessert claims he is like a big bird, dropping fresh seed on the ground.

Mark Thompson produces art not about, but in community with, bees. For the Langton show he installed a plexiglas box encasing a working hive. A mesh tube led out of the box and through the gallery skylight. The bees used the tube as a portal for their foraging. Underneath the hive was a chair, in which Thompson could sit, his head stuck through a hole in the bottom of the hive case.

We are taught to dread bees — some gardeners avoid plants that attract them — so it was a pleasure to be inches away, observing them as they lived their collective lives, hatching from cells, leaving and returning from foraging, falling dead to the bottom of the box. I thought of the similarities between Thompson’s work and that of gardeners, who take from the world a subject they find fascinating and accentuate its special features by displaying them in a contrived setting. Thompson displayed the bees not for our superficial entertainment but to alter our association with them through the mutual influence that the term community should imply.

I visited Thompson at another installation and came away even more intrigued by his art. Intensely intellectual, articulate, and somewhat shy, he describes the dances the bees perform to communicate to each other the exact location, as far as several miles away, of nectar laden flowers. Based on the research of entomologist Karl Frisch, Thompson can interpret the dances and locate within a block the flowers the bees are signaling.

Thompson is particularly interested in the urban environment, and his ventures with the bees are a way of exploring the human social life around him. As he puts it, bees are a “flying bridge” between himself and the community. He talks to the people he encounters, many of them gardeners, and documents his excursions in a journal. The flowers he finds by following the bees are pressed and mounted and texts are composed for display. Ultimately, he wants to spend several weeks living with the bees, resting in a flotation tank, and document the experience on film, the narration of which will be a reading of a dream journal he will keep. He hopes to discover the effects on his consciousness of close association with another life form that, like our own species, is intensely social. He hopes to visualize other ways people could live together — by relaxing some of the strictures of individuality and by using systems of communication that are not linguistic.

Gardeners have always been thinkers as well as aesthetic shapers of the world, and gardening is an eminently social activity, open to dialogue not only with gardeners but with other groups in society. Environmentalists and architects are groups that we are used to talking to; artists are another group with whom we may have lively, intelligent conversations.

Langton Arts’ Post Nature show asked difficult questions about what we mean when we talk about nature and if, in fact, “nature” is still a useful term. The subtitle of the show was Flora, Fauna, and the Collapse of the Natural. Can we stop seeing nature as something external on which to project the qualities of cruelty or benevolence, the roles of dictatorial arbiter or trenchant foe? Gardeners, who are artists who work with what we call nature as a medium, are in a special position to consider, and respond to, this question.

Responses