Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need

Once part of the ancient southern supercontinent, Gondwanaland, New Zealand is the world’s most isolated land mass of its size. With latitude extremes roughly corresponding to those of Los Angeles and Seattle, New Zealand has climates ranging from subtropical to temperate to alpine.

New Zealand is frequently and often incorrectly associated with (and indeed was once connected to) its nearest neighbor Australia, though they are separated by a thousand miles of open ocean. In reality the two have little in common biogeographically, with radically different geologic and climatic histories. Australia is an extremely old, geologically stable, and arid continent whose major landforms are the result of millions of years of weathering. By contrast, New Zealand is part of the “Ring of Fire”—a young land shaped by earthquakes and volcanic activity. Their flora and fauna also differ significantly, although there are affinities between New Zealand’s alpine and cool temperate flora and that of southeastern Australia and its island state, Tasmania. Though these regions share some species, eighty-five percent of New Zealand’s flowering plants are endemic to the islands. An important component of the vegetation are the twenty endemic conifers, which are of ancient and largely tropical ancestry.

Some botanists believe that in the absence of native browsing animals, the recently extinct, ostrich-like moas perhaps exerted a significant enough grazing threat to the vegetation to explain the evolution of a number of curious and unexpected plant forms. How else can we account for the presence of spiny, sharp-leaved, or otherwise armed plants such as those in the genus Aciphylla–the aptly named speargrasses? These carrot relatives have stiff, dagger-like leaves and are reminiscent of Yucca whipplei. Other curiosities abound, including many species with few or tiny leaves, a character more typical of arid zone vegetation. This trait is sometimes coupled with a wiry, twiggy, divaricating growth habit that results in a tangled mass, often appearing dead and unappetizing. Some plants only have these apparently unpalatable characteristics when young, assuming a more “normal” appearance when they’ve grown beyond the presumed reach of the ten-foot-tall moas. Many plants undergo several transformations on their path to maturity. Perhaps the most dramatic example is the lancewood (Pseudopanax crassifolius), whose juvenile and adult stages differ so much that they were originally described as separate species.

In another contrast to Australia, brightly colored flowers are relatively uncommon in New Zealand’s flora. This can be accounted for by the paucity of specialized pollinators whose flower-visitation habits are triggered by response to color. Instead one finds a preponderance of white-flowered plants, readily discernible in the darkness by the exceptionally numerous nocturnal moths that are among the pollinators. But color abounds elsewhere in New Zealand’s flora, for I know of no other with foliage in so many shades of brown or orange, along with such a large number of colored and variegated cultivars. To add to the palette, these foliage colors intensify in cold weather, even in the mild winters of southern California.

With its extremes of latitude and range of climates, New Zealand’s diversity of plant life provides an ample number suitable for cultivation in western North America. Though New Zealand enjoys a cool maritime climate with abundant rainfall, in cultivation many of its plants tolerate drought, once established. In this article, we’ll look at some of those suitable for southern California.

New Zealand Conifers

The most majestic member of New Zealand forests is the kauri (Agathis australis), a member of the subtropical araucaria family. The kauri was originally found throughout the northern half of North Island, but has been severely depleted by logging. This magnificent long-lived species has a clean, straight, massive trunk once prized for ship’s masts. In the forest the lower branches are continuously shed and trees have only a high crown of foliage, but in cultivation the branches may be retained to ground level giving a narrow columnar form. Unlike most conifers, kauri has flat, lanceolate leaves, reddish-brown when young, becoming olive green with maturity. Though kauri can eventually reach over one hundred feet tall, its growth rate is sufficiently slow to make it suitable for garden cultivation. The largest specimen I know of is in Balboa Park in San Diego, measured at fifty-two feet tall in 1994. However, it is scarce in gardens; propagation is most successful from fresh seed, which is difficult to obtain, but is also possible from cuttings—even leaf cuttings. The specimens cultivated at the Huntington in the early half of this century are no longer living, but a tree grown from seed received in 1984 and planted in 1991 is about fifteen feet tall and thriving. I also received fresh seed in 1991, which germinated abundantly enough to afford planting of a dozen trees, as well as distribution to other gardens.

The New Zealand podocarps (Podocarpaceae) are the most distinctive elements of the lowland forests, and though conspicuous there, are uncommon in cultivation here. The totara (Podocarpus totara) is one of the grand giants of the mixed conifer/broadleaf forests on both islands. Its timber was the most highly valued by the Maori, being superior for canoes and favored for constructing the beautifully carved meeting houses. The Huntington specimens were present at the time of the first grounds survey in 1932, and continue to grace the southern walk along the Rose Garden. These exhibit the typical squat round-headed shape of cultivated specimens, in contrast to the tall massive form seen in its native forests. Another of the characteristic forest giants is the rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum). The long weeping branchlets of its juvenile stage give it a distinctive grace for many decades before mature growth appears. Our specimen, over thirty years old, was grown from a cutting from the old one at Strybing Arboretum; it is in the upper ravine of the Japanese Garden, a cooler more humid area of the Huntington thought to be most suitable for its growth. Though this specimen is thriving, we have been unable to establish cutting-grown progeny elsewhere in the gardens.

At the other end of the size spectrum is the pygmy pine (Lepidothamnus laxifolius), the smallest of all conifers. At first mistaken for a moss by its discoverer, it is a prostrate shrub of boggy sub-alpine areas. It has not been successful at the Huntington, and is more suited to a moist rock garden situation where summers are not as hot. More adaptable is the mountain totara (Podocarpus nivalis), a variable shrub that grows well here in the arid flatlands, despite its alpine origin. One of the most interesting of the podocarps is the matai (Prumnopitys taxifolia), which develops through several morphological forms on its way to adulthood. In the garden, our juvenile plant looks quite dead, enough so that I have to occasionally remind the gardener that it is, in fact, alive. One must look closely to see the few and scattered tiny leaves along the brick-red stems. Though an excellent educational tool here, it takes a creative plant connoisseur to envision a garden home for this “Cousin It.”

The palm genus Rhopalostylis has only three species: R. baueri from Norfolk Island, R. sapida from New Zealand, and R. cheesemanii from New Zealand’s Kermadec Islands. Known as nikau, R. sapida has the most southerly distribution of any palm, as far south as 44˚18’ in the Chatham Islands. Despite this, it is not hardy, being found in warm lowland forests. Nikau gives a decidedly tropical look to many areas of northern North Island and along the west coast of South Island. Stiffly held fronds give the appearance of a shaving brush or feather duster, from which its other vernacular names are derived. The fallen fronds leave distinct rings on the trunk, and the crown base is clearly swollen and bulbous. It is very slow-growing, and our plants, over sixty years old, are only twenty feet tall.

Flowering Trees

Tropical appearance is also a feature of the puka (Meryta sinclairii), a small multi-trunked tree in the Araliaceae. The huge, glossy, oblong leaves can be up to twenty inches long on stout foot-long petioles. Puka does not tolerate much frost so is best suited to mild-winter regions; our fifty-year-old plant is in a sheltered area of the Jungle Garden. It makes an excellent container plant. A stunning yellow and green variegated form called ‘Moonlight’ is pictured on the cover of Lawrie Metcalf’s The Cultivation of New Zealand Trees and Shrubs. A tantalizing but not-for-sale sight at a nursery in New Zealand years ago, it is slow growing and difficult to propagate and still virtually unobtainable.

Perhaps the most well-known flowering tree of New Zealand is the pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa), also called the New Zealand Christmas tree for its brilliant crimson flowers in the antipodean summer. This dense round-headed tree blooms best in coastal areas; here, thirty miles inland, our seventy-year-old specimens have never bloomed. Many fine specimens can be seen in Palisades Park and elsewhere in Santa Monica, some clothed with aerial roots. Forms with yellow or pink flowers or variegated foliage are known. Occurring near sea level in northern North Island, it is rather tender, as is M. kermadecensis, found in the Kermadec Islands. A sparse bloomer in comparison, M. k. ‘Sunninghill’ is nevertheless an attractive foliage plant, with yellow marbling in the leaf centers. Several species of Metrosideros, such as M. carmineus, start life as climbers. Two cultivars of this tiny-leaved species have been selected from adult growth and make open three-foot garden shrubs or container plants. ‘Ferrous Wheel’ (syn. ‘Ferris Wheel’) is completely covered with carmine flowers in spring, as is ‘Carousel’, differing only in its yellow-margined leaves. Both cultivars originated at Duncan and Davies Nursery, a decades-old New Zealand purveyor of native and other plants and the source of many of the Huntington’s New Zealand plants.

To my frustration, all attempts at cultivating New Zealand’s floral emblem have failed here. The two species of kowhai (Sophora tetraptera and S. microphylla) are sparsely foliaged leguminous trees with brilliant yellow pendulous flowers. S. microphylla is also found in Chile, evidence of the existence of ancient Gondwanaland. A good one for gardens is S. tetraptera ‘Gnome’, a slow-growing shrub eventually reaching six feet tall, but flowering when still quite small. Whenever we’ve tried to grow any species of Sophora here, tent caterpillars seem to quickly appear en masse out of nowhere and by the time they are noticed the plants are completely denuded. One or two have escaped this plague and survived for a few years, but I eventually just admitted defeat with this genus. I was rewarded in New Zealand on a recent trip, when a fortunate late bloom provided quite a show.

Familiar Shrubs

Among the most familiar shrubs are the hebes, New Zealand’s largest genus of flowering plants with around eighty endemic species and many times more cultivars. The whipcord types, so-called for the appearance that their tightly appressed leaves give them, are unusual and desirable alpines difficult to cultivate in southern California; several have been tried and have failed at the Huntington. The remaining species are leafy shrubs, from one to five feet tall, and typically summer-blooming. Many are native to seashores, and are excellent garden subjects for that situation. In our hot inland climate they prefer some shade and ample water, and though they grow fast, tend to be somewhat short-lived. They root so easily and quickly from cuttings that we just repropagate them when they start to look ragged. One of the showiest, though tender, species is the napuka (Hebe speciosa) with large cylindrical spikes of magenta or purple flowers and two- to four-inch long, deep, glossy green leaves. It has been extensively used for hybridizing, but unfortunately the lack of hardiness persists in the offspring. The old and well-known hybrids H. ‘Alicia Amherst’ and H. ’La Seduisante’ have H. speciosa as a parent, as does H. x franciscana ‘Blue Gem’, a neat four-foot shrub with violet flowers. H. speciosa ‘Pink Spike’ is a more recent selection with intense fuchsia-colored flowers. Good for draping off a wall or raised area, H. hulkeana and its cultivar ‘Lena’ are low sprawling shrubs with toothed leaves and spectacular branching sprays of pale violet to white flowers. H. ‘Oratia Beauty’ is a four-foot shrub with distinctly two-ranked elliptical leaves along sinuous stems at whose tips are short spikes of pink and white flowers.

Certainly familiar, too, are manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) and its cultivars. Manuka and its cohort kanuka (Kunzea ericoides, syn. L. ericoides) are the commonest shrubs of scrubland throughout both islands. Its more well-known vernacular name, New Zealand tea tree, suggests a culinary use; indeed, infusions of vitamin C-laden leaves once saved many a voyager from scurvy. In habitat manuka is a heath-like shrub with fragrant white flowers; the numerous cultivars range in color from white through shades of pink to cerise, the flowers smothering the plants in winter-spring. The most extensive breeding was done in southern California by Dr Walter E Lammerts, then of UCLA and later Descanso Gardens. One of the best is ‘Ruby Glow’, with ruby-red flowers and reddish-bronze foliage, reliably providing a festive Christmastime display. A series of dwarf selections, named after native birds such as ‘Kiwi’ and ‘Kea’, was developed by Duncan and Davies Nursery and make attractive container plants.

Wellington, New Zealand

Some New Zealand plants, though rare or barely accessible in habitat, are well-known in cultivation. The kaka beak (Clianthus puniceus) is naturally restricted to just a few sites in eastern North Island. It is one of the most popular cultivated shrubs in New Zealand and was one of the few plants cultivated by the Maori purely for ornament. This member of the pea family has spectacular pendulous clusters of two- to three-inch scarlet flowers; both pink and white cultivars are known as well as a var. maximus with larger flowers. Its sparsely foliaged, open habit lends it to a variety of uses. Though in cooler areas it can tolerate some drought once established, in southern California it needs consistent watering and dappled or light shade. As in its native home, it tends to be short lived here and susceptible to leaf miners and witches-broom-inducing eriophyid mites. The Marlborough rock daisy (Pachystegia insignis) inhabits rocky cliffs and gorges of the northern South Island coast, often in association with Hebe hulkeana. This one- to three-foot shrubby daisy prefers a warm sunny dry situation and well-drained soil. The large, leathery, glossy leaves have a distinct white central vein and thick white felt beneath, with the new leaves completely felted. The stems and long drumstick-like flower stalks are also clothed with white hairs. Some forms have golden-brown or bronzy tomentum. Yellow-centered white daisies appear in spring. The similarly distributed rengarenga or rock lily (Arthropodium cirratum) has a rosette of pale green, drooping strap-like leaves. I was inspired by a mass planting under the low canopy of a tree in the Auckland Regional Botanic Garden, and did a similar planting here under the deep shade of a strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo). It is ideal for this purpose, the two-foot-tall branching panicles of snow-white flowers lighting up the shade. Its main drawback is that it also serves as excellent snail bait.

Island Rarities

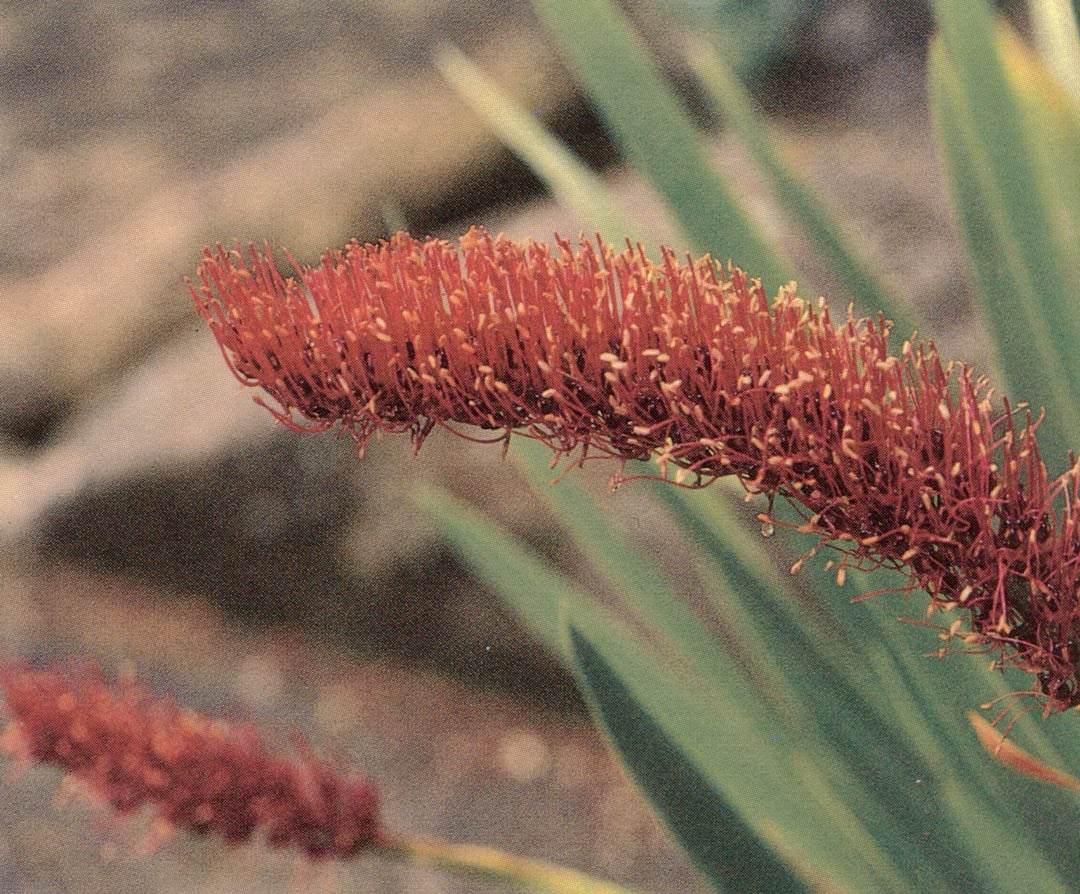

New Zealand’s offshore islands are home to many showy flowers, much more so than on the main islands, and some of these are cultivated. One of the rarest plants in the world is the bignoniaceous vine Tecomanthe speciosa, known in the wild from only a single individual in the northerly Three Kings Islands, from which all cultivated plants have originated. Propagation can be by cuttings or seed, as it is self-fertile; interestingly, the seedlings show some variability. The vigorous rope-like twining stems need a sturdy support such as an arbor or tree, to which it must be tied to start it upward; otherwise it can sprawl along the ground in a heap. Large, glossy, compound leaves add to its subtropical flavor, and it needs frost protection in cold areas. Clusters of greenish-white tubular flowers are produced cauliflorously on old wood. The Poor Knights’ lily (Xeronema callistemon), grows on coastal rocks and cliffs of the Poor Knights’ Islands. It has clumping fans of rubbery sword-like leaves and a bent brush-like spike of flaming crimson flowers. In cultivation, it needs to be grown lean and mean, in keeping with its natural habitat; it does especially well when root-bound and is an excellent container plant. Needing many years to reach flowering stage, our ten-year-old plants never got enough of a chance, having been thoroughly annihilated by a falling tree in a severe windstorm in January 1997.

The endangered Chatham Islands forget-me-not (Myosotidium hortensia) is no doubt one of New Zealand’s most spectacular plants and a desirable but tricky horticultural subject. Though it grows on the exposed rocky seashore, in cultivation it needs a cool, moist, humusy soil in shade. I can confirm its impossibility in hot southern California, as I have watched well-watered plants in the nursery melt practically before my eyes with the first breath of summer heat. Other, cooler western climes suit it better, and it is well worth the attempt, even if just for the rosette of glossy, fleshy lettuce-like leaves. These cradle a hydrangea-like cluster of five-petalled flowers, sky-blue in the center becoming paler toward the edges.

In a future article, we’ll look at plants grown mostly for their foliage, such as Coprosma, Pseudopanax, Phormium, Carex, and Cordyline.

Kathy Musial will lead a Pacific Horticulture tour to New Zealand in November, 2000. See the announcement on page 64.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Responses