Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens and Design

The author’s Gardening With Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest was published recently by University of Washington Press. In it he deals more fully with the plants of the region covered here, and with those of the region east of the Cascade Range. The book is reviewed in this issue.

A benign, temperate climate extends along our botanically rich Pacific Coast from the San Francisco Bay Area to southwestern British Columbia. The many gardens throughout this vast stretch of land play host to plants of many lands. The best of plants from the Orient, Europe, and other faraway places luxuriate in gardens of our coastal belt. Yet just beyond the confines of our Pacific Northwest gardens, there are many wildlings of forest, rock outcrop, prairie and seacoast that can bring added charm and color to the cultivated spaces nearby.

It would take many chapters to do this native treasure justice. Rather, I shall draw upon a few gems from this horticultural bounty of natives to tempt the gardener. Some will be well known to specialists in natives, but most will be making their debut in the mainstream of garden literature.

The territory in which this largely untapped treasure resides includes the North Coast country of northwestern California, the coastal mountains and seacoasts of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, the Rogue, Umpqua, and Willamette valleys of Oregon, the lowland valleys of western Washington (Puget Sound basin and nearby drainages) and the timbered western slopes of the Cascade Range. To many of us this is the heartland of the wetter Pacific Northwest.

Lest the reader fear that growing natives must be a total commitment, with all the exotics from China, Japan, New Zealand, and elsewhere relegated to the compost, be assured that a successful compromise can be reached. Any garden can be a blend of the exotic and the native. We grow Douglas fir, salal, Oregon grape and native penstemons right along with New Zealand hebes, Chinese rhododendrons and alpines from Switzerland. Life styles of all of these can be compatible, once form, texture and habitat are harmonized. For some localities along the Pacific Coast, being a nut about natives can be ecologically and economically sound. Water-conserving gardeners in chaparral land can have that distinction. But our more temperate country of the North Coast to British Columbia is less demanding, letting us choose among charming plants of both local and exotic origins.

Here, a sampler from among our native plants is offered, grouped for particular garden settings and situations, each of which has its own mixture of sunshine and shadow, wetness and dryness. Background plantings first, followed by special places like the shrub border, the perennial bed, the rock (or alpine) garden and those many places calling for ground covers. Tempting the reader with examples of outstanding natives is not enough, and as a finale l offer some counsel on how they may be acquired for your garden.

Some Native Trees

Trees dominate the Pacific Northwest. Vast stretches of coniferous evergreens have populated the cool, winter-wet coastal country for millennia. The common lowland conifers become a part of urban horticulture almost unintentionally. Coast redwood, Douglas fir, western hemlock, shore pine and western white pine appear in gardens frequently, usually as volunteers or left by developers. But there are several other conifers that should be used more. Three needle-leaved conifers are outstanding garden plants: mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) and Brewer’s (or weeping) spruce (Piece breweriana). Each is slow-growing and moderate in stature and has superior foliage. Mountain hemlock is a peerless conifer, with its dense glaucous needles and informal habit. It does well as a bushy small tree in the larger rock garden or as a container plant.

We are blessed with several broadleaved evergreen trees, four of which are outstanding ornamentals: golden chinquapin (Chrysolepis chrysophylla), tan oak (Lithocarpus densiflorus), canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis) and madrone (Arbutus menziesii). The two-tone leaves of the chinquapin is a lovely surprise: dark green above and golden yellow beneath. Mature trees up to thirty feet tall may bear chestnut-like seed burs. The tan oak, though so common as to be a forester’s weed tree in the mixed woodlands of southwestern Oregon and northern California, makes an elegant specimen for the garden. With boldly veined leaves and copious acorns, it can reach twenty to forty feet in cultivation. Its rare, cut-leaved form, Chrysolepis chrysophylla forma attenuato-dentatus is now being propagated for sale. A shrubby variety of tan oak, largely restricted to serpentine soils in southwestern Oregon and adjacent California, Lithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides, is a superb variant with smaller, grey-green leaves. There seems to be a host of forms of the canyon live oak; some shrubby with sharply serrated leaves, others are medium-sized trees with a single trunk and entire or serrate evergreen leaves. It, too, has two-toned leaves — glossy dark green above and silvery beneath. It makes a grand tree in cultivation as far north as Puget Sound, Washington.

Throughout the full length of the Pacific Coastal belt, one encounters the exquisite madrone, Arbutus menziesii. Though sometimes disparaged for its litter of leaves and bark in late summer, the glorious foliage of broad smooth leaves, the satiny smooth, reddish trunk and the showers of white flowers give it outstanding garden quality. Two or three drawbacks, aside from the litter must be admitted: first, madrones are hard to establish. Small seedlings should be set in place and not disturbed after thinning to the one desired. Then, mature madrones can create a demanding habitat for other ground level plantings. Nature’s lessons can be observed, though, by growing under madrone what grows there in nature — create a native garden at its foot. A final caution: in some places, madrones are hard hit by several plant pathogens causing severe dieback and even death of mature trees. But take a chance — a madrone in the garden can be a thrilling sight.

Deciduous trees abound in our woods throughout the Pacific Coast states, even though conifers usually dominate the scene. Maples, dogwood, cherry, ash, birch, willow, oak, alder and cottonwood are suited to our coastal environments. Three outstanding deciduous trees have been successfully domesticated. By far the most satisfactory is the small, often multi-stemmed vine maple, Acer circinatum. Its elegant form and foliage approach the Japanese maples A. palmatum and A. japonicum in elegance. Two deciduous oaks, Garry oak, Quercus garryana, and California black oak, Q. kelloggii, are seen occasionally as intentional plantings in large gardens or parks. For many coastal gardeners, the Garry oak is simply a standard item in the urban landscape, from Victoria, British Columbia and Tacoma, south to northern California.

The glory of our deciduous woodland trees surely must be the Pacific flowering dogwood. A small tree of beautiful form in trunk, branch tracery and foliage, it comes radiantly alive in spring with its showy cream white flowers — in reality, four or five sterile showy bracts around a pincushion of tiny flowerlets. Dogwood can be both a joy and a despair. When healthy, it is garden perfection, but when stricken with the anthracnose fungus, it suffers and may die. Gardens of low humidity or where no anthracnose disease has struck, should enjoy the full benefit of this superb native tree.

Native Shrubs

While the chaparral areas of California are epitomized by their shrubs, other habitats in our more northern coastal domain can boast a fine array of evergreen and deciduous shrubs, too. Many of them are found at eye-level in our forests. The following lists suggest a few outstanding coastal natives for the garden.

Evergreen Shrubs

Shrub tan oak (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides)

Deer oak (Quercus sadleriana)

Huckleberry oak (Quercus vaccinifolia)

Coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica var. crassifolia)

Salal (Gaultheria shallon)

Evergreen huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum)

Hairy manzanita (Arctostaphylos columbiana)

Rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum)

Blueblossom (Ceanothus thyrsiflorus)

Mountain balm (Ceanothus velutinus var. laevigatus)

Tall Oregon grape (Berberis aquifolium)

Low Oregon grape (Berberis nervosa)

Silk-tassel bush (Garrya elliptica)

California wax-myrtle (Myrica californica)

Oregon box (Paxistima myrsinites)

Kalmiopsis (Kalmiopsis leachiana)

Deciduous Shrubs

Red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum)

Gooseberry (Ribes lobbii)

Serviceberry (Amelanchier florida, A. cusickii)

Oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor)

Deerbrush (Ceanothus integerrimus)

Mock-orange (Philadelphus lewisii)

Devil’s club (Oplopanax horridum)

Indian plum (Oemleria cerasiformis)

Two shrubby evergreen oaks easily merit the spotlight. The deer oak (Quercus sadleriana), confined to the upper montane forests of the Siskiyou Mountains, is distinct among the west American oaks. Broad, heavily veined leaves of leathery texture copiously clothe a branching trunk four to nine feet in height. Happiest as an understory shrub in open coniferous woods, it performs beautifully in Northwest gardens. The other evergreen oak, the huckleberry oak, Q. vaccinifolia, takes best to open sunny places in the garden. It is a shrubby facsimile of the canyon oak. Gardens on the outer coast cannot be without the California wax myrtle, Myrica californica; windswept dunes where beach homes now multiply are perfect settings for this handsome, tall evergreen.

The silk-tassel bushes are truly western innovations and one of the best is Garrya elliptica. This superb, tall, shrub, with its symmetrical, wavy-margined leaves, gives an exuberant show in spring. If it is a male plant the long yellow pollen tassels are a fine sight. Cultivars like ‘James Roof’ and ‘Pat Ballard’ have even showier tassels.

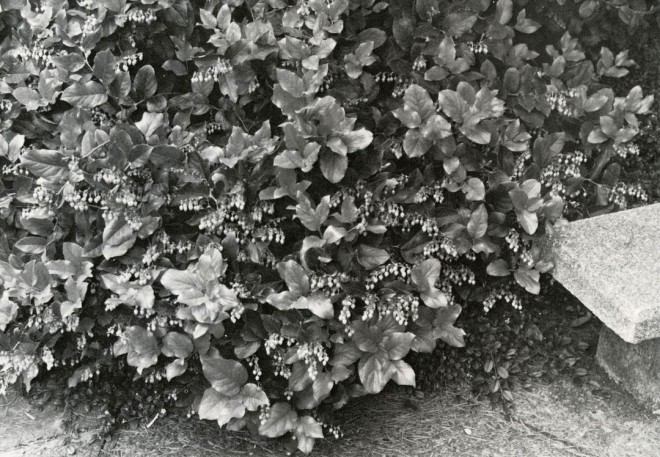

The evergreen shrub story is not complete without mention of two durable woodlanders, salal, Gaultheria shallon, and evergreen huckleberry, Vaccinium ovatum. The leathery broad-leaved salal is at home in dense or open woods the full length of our chosen territory. It and the narrow-leaved evergreen huckleberry have showy white flowers and edible fruits. Both are being discovered by gardeners nowadays, after years of downright criminal neglect, as evergreens of horticultural value.

The red-flowering currant, Ribes sanguineum, must be the oldest of our Northwest natives in cultivation. By the 1830s, it was popular in Britain following David Douglas’ initial harvest of seed. More cultivars are

known of this than any other native shrub. Either the cultivars or the wildlings from nearby woods will give brilliance in reds, pinks to whites in early spring. Its fuchsia-flowered relative, Ribes lobbii (a gooseberry) is a more temperamental charmer. An outstanding shrub that takes pride of place in the mock-orange clan — Philadelphus lewisii — is considered the best of them all by British authorities. Many an azalea cultivar is tinged with the blood of our west coast Rhododendron occidentale, the western azalea; to most it contributes its glorious scent, but several selections from among wild plants are outstanding in the garden without benefit of special hybridization.

Native Ground Covers

The list of native ground covers is impressive and the variety of places they can carpet are many. Here is a select short list of native ground covers with their stature and requirements for sun or shade.

Kinnikinnik (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) — sun, three inches

Media manzanita (Arctostaphylos media) — sun, twelve to eighteen inches

Mahala mat (Ceanothus prostratus) — sun, prostrate

Squaw carpet (Ceanothus pumilus) — sun, prostrate

Common juniper (juniperus communis, vars. montana, jackii) — sun, prostrate

Beach strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis) — sun to partial shade, six inches

Wild ginger (Asarum caudatum and A. hartwegii) — shade, four inches

Inside-out flower (Vancouveria species) — shade, twelve inches

Bunchberry (Cornus canadensis) — shade, three inches

False lily-of-the-valley (Maianthemum dilatatum) — shade, three inches

Wood sorrel (Oxalis oregona) — shade, four to six inches

The vancouverias, known as inside-out flowers, come in three kinds: two white flowered ones, Vancouveria planipetala, evergreen, and V. hexandra, deciduous; and the yellow V. chrysantha. Most rampant is V. hexandra, but its aggressiveness is tolerable in larger woodland settings. All have exquisite compound leaves with three angular leaflets. The wild gingers, Asarum caudatum and A. hartwegii, are choice woodland carpeters with heart-shaped leaves — marbled in A. hartwegii — and curious vole-sized flowers. They are terrorized by slugs!

Two other woodland groundcovers must be recommended, but with due caution for their rampant, invasive nature. False lily-of-the-valley, Maianthemum dilatatum, a member of the lily family, runs by underground rhizomes; the plant disappears from view totally in the winter but asserts itself aggressively in spring. It has heart-shaped leaves and small spikes of white flowers, followed by reddish berries. Equally invasive is the wood sorrel, Oxalis oregona. Its large clover-like leaves and attractive pinkish flowers are familiar in the green carpet of redwood and other coastal conifer forests. Both are best for naturalizing in the wilder parts of the woodland garden.

Natives for Perennial Borders

There are so many candidates for this category that any short list is arbitrary.

Perennials

Sword fern (Polystichum munitum)

Anderson’s sword fern (Polystichum andersonii)

Deer fern (Blechnum spicant)

Chain fern (Woodwardia fimbriata)

Oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

Columbine (Aquilegia species)

Goat’s beard (Aruncus sylvester)

Bleeding heart (Dicentra formosa)

Penstemons (taller species of Penstemon)

Fawn lily (Erythronium species)

Tiger lily (Lilium columbianum)

False Solomon’s seal (Smilacina racemosa)

Fairy bells (Disporum hookeri)

Fringe cup (Tellima grandiflora)

Grass iris (Iris tenax)

Wake-robin (Trillium ovatum)

Ferns, so much a part of our Northwest scene, take well to the garden border, in filtered sun or shade. I cannot choose among the five listed; they are all superb. For low groundcover use, oak fern is unsurpassed. For dampish places in the garden, the large evergreen chain fern is majestic. Anderson’s sword fern makes a charming substitute for the common, though elegant, sword fern (Polystichum munitum).

Fawn lilies (or avalanche, or glacier lilies) are colorful hallmarks of early spring in the Northwest. The lowland ones like Erythronium oregonum and E. revolutum are easy garden plants once established and kept free of slugs. The other native lilies — true lilies that is — entice the gardener, but only the common Lilium columbianum is available.

An imposing border plant of three to five feet is goat’s beard, Aruncus sylvester. It reminds one of a large white astilbe or sorbaria. Its large compound leaves are surpassed by a massive plume of tiny white flowers, showiest in the male plant.

The tallest of the saxifrage clan is the fringe-cup, with its eighteen-inch stalks of cream flowers. Up close, each flower is an exquisite geometry of dissected petals. A curious hybrid has been found in Oregon, between the fringe-cup and the familiar piggyback plant (Tolmiea menziesii); it is being propagated by Dr David Wagner of the Detling Herbarium, University of Oregon, who hopes it may become available in nurseries.

Our two columbines, Aquilegia formosa and A. flavescens, are second best only to the Rocky Mountain species, A. coerulea, The red columbine (A. formosa) is widespread in the Northwest from nearly sea level to timberline; the yellow one (A. flavescens) is montane, mainly east of the Cascade crest. Both take well to the garden, in wettish sunny places.

Each member of the iris clan in the Pacific Northwest is a garden delight. In particular, the fine lovely irises, Iris innominata and I. tenax, are fine for the open woodland border, the rockery or the perennial border with full sun.

Some Natives for the Rock Garden

The alluring art of rock gardening with alpines and low-growing cushion plants has made use of Pacific Coast natives ever since the Englishman Reginald Farrer captured the attention of early 20th century gardeners with his extraordinary prose. A number of plants, like the lewisias, sedums and penstemons, are fully integrated into the rock garden. Other northwesterners are known only to connoisseurs and still others have yet to be tested in the alpine garden. The following list just opens the lid on a treasury of plants for rock gardens.

Rock Garden Plants

Lip fern (Cheilanthes gracillima)

Rock brake (Aspidotis densa)

Bulbs of fritillaries, calochortuses, brodiaeas and alliums

Lewisias

Penstemons

Douglasia laevigata

Wild buckwheats (eriogonums)

Alpine fleabanes (erigerons)

Grass irises (Iris tenax, l. innominata)

Alaska spiraea (Luetkea pectinata)

Petrophytum

Stone-crops (sedums)

Saxifrages (Saxifraga bronchialis, S. cespitosa)

Phloxes

Jacob’s ladders (polemoniums)

The succulent leaved lewisias love the sunnier rockery. Most commonly planted are the many forms (and hybrids) of Lewisia cotyledon, native to the Klamath-Siskiyou country.

But meriting further testing are L. rediviva, L. columbiana and L. leana. Of course, the superb L. tweedyi of the Wenatchee Mountains and North Cascades is a perennial challenge; first to come by plants of it (without digging it in the wild), and then to keep them happy in the garden. Penstemons of all sizes abound in the Northwest. And a generous number are low-growing and eminently suited to the rockery. First place must go to Penstemon rupicola, that cliff-hugging gem with glaucous leaves and purplish-red flowers. Others of outstanding quality are P. davidsonii, P. procera subsp. tolmiei and P. cardwellii. So easy from cuttings, these penstemons are great for the novitiate in rock-gardening. So easy a clan must have a fault. Reginald Farrer, doyen of the rock garden cult, says of their short-lived disposition: “penstemons usually having but a lush constitution, prefer a crowded hour of glory rather than a long existence of mere usefulness.” Their brevity can be overcome, so easily do they come from cuttings.

We have been delightfully surprised by the good nature of Alaska spiraea, or partridge foot (Luetkea pectinata). This subalpine carpenter takes to sea level gardens well. It makes fine low masses of dissected green leaves and spikes of cream-white flowers.

The petrophytums, kin to spiraeas, are elegant mat-formers. The Olympic Mountain plant, Petrophytum hendersonii, has proved most adaptable and is eye-catching in an alpine trough garden. The douglasias, kin to primulas, are also mat-formers. While the montane ones are a bit miffy in the winter in northwest rockeries, I predict that the form of Douglasia laevigata found in the Queen Charlotte Islands will be a winner, once it becomes more available. On the island it is subject to much rain and grows on exposed, exquisitely dissected rock outcrops just above the salt spray. So it should be tolerant of our northwest wet.

[sidebar]

Native Plant Societies

California Native Plant Society

Suite D, 2380 Ellsworth Street

Berkeley, CA 94704

Native Plant Society of Oregon

c/o David Wagner, Dept. of Biology

University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403

Washington Native Plant Society

c/o Arthur Kruckeberg, Dept. of Botany

University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195

Northern Nevada Native Plant Society

c/o Margaret Williams

P.O. Box 8965, Reno, NV 89507

[/sidebar]

There is no easy, supermarket approach to acquiring most of our northwest natives for the garden. Some are available in the few nurseries specializing in native plants, such as those advertising in this publication. Others may be had through plant sales and seed lists of botanic gardens and the several western native plant societies. Many of these are also mentioned in Pacific Horticulture. Collecting in the wild may be the best way for many of them — once one gets the hang of it. Collecting live plants is both ethically taboo and in practice fraught with failure. Plants from seeds or cuttings taken in the wild are so much more reliable and aesthetically rewarding. And we have a growing literature on the cultivation of western natives; aid and comfort for the daring gardener is now at hand.

Like the box of candy with one of each to tempt, this introduction to natives of the Pacific Northwest is but a sampler. May it encourage gardeners and plantsmen to use these fine plants in our coastal urban settings.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses