Contributor

- Topics: Archive

The desire to have a vibrant garden is often at odds with the reality of a severe drought. This is the story of a Los Angeles couple that didn’t wait for water restrictions to control their tropical paradise.

Purchased by the current owners in March 2009, the California/Mediterranean-style house, one of the original homes in the Pacific Palisades area of Los Angeles, was built in 1929. The centerpiece of the property is a tropical garden featuring diverse, exotic plants with several fountains, koi ponds, a swimming pool and spa, a bromeliad grotto, a rose and citrus garden, a greenhouse, and a succulent garden laid out on the hillside property. Highlights of the lush and diverse plantings include a stunning non-fruiting olive (Olea europaea) that shelters a massive night blooming cereus (Hylocereus undatus) as well as mature Aleppo pines, numerous palms, several varieties of ginger, taro, ferns, orchids, and aquatic plants. Edibles in the garden include fruit trees such as mango, papaya, guava, banana, apple, peach and plum, several lemon and lime varieties, Satsuma and pixie mandarins, Valencia orange, and blood orange—as well as a container garden with vegetables and herbs.

In response to historically tremendous water bills, I was hired to improve the water efficiency of the garden without compromising the integrity of the original design. Tackling the challenge of how to efficiently irrigate an established, not-so-climate-appropriate large garden was a multi-step process. My goal was to wean the plants off years of excess irrigation and slowly alter the plant palette to be more climate-appropriate while maintaining a similar “California tropical” style in keeping with the architecture of the house.

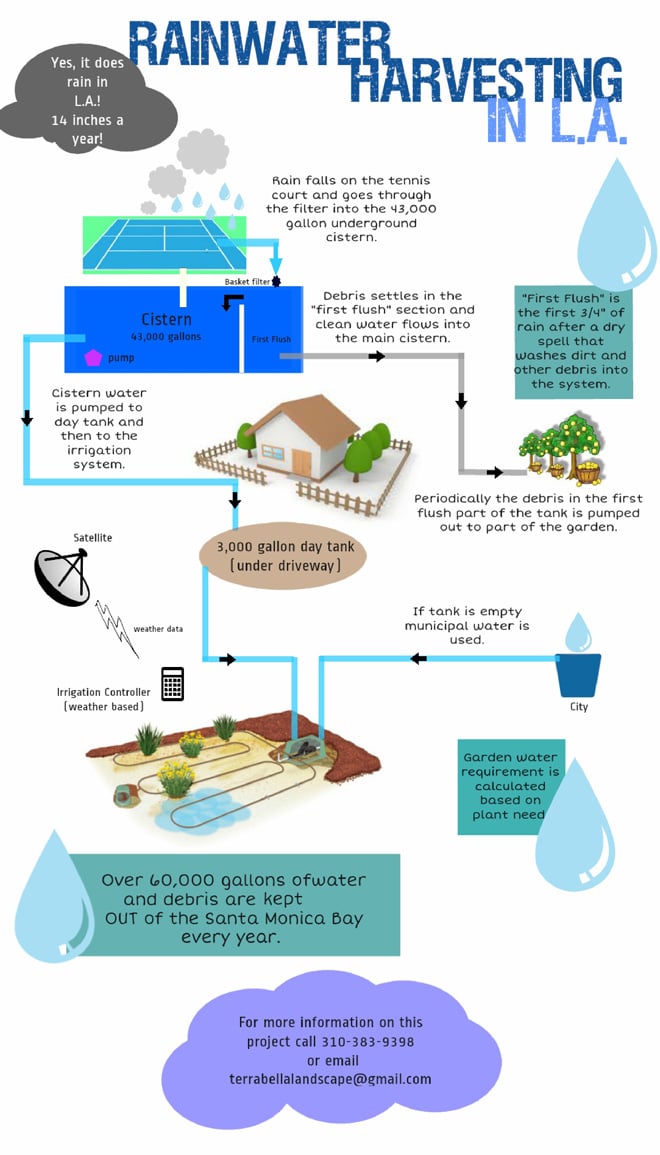

We began the process by looking at alternatives to the garden’s extensive traditional irrigation system, and considering the most basic starting point: the water source. Previous upgrades to the drip irrigation system included a weather-based irrigation controller, which provided some water savings—but many of the plants would not tolerate severely reduced hydration. The addition of a rainwater harvesting system ensured that the garden would be independent of extreme water restrictions and, at the same time, significantly reduce runoff into an already overburdened storm drain system. Keeping water on the site and reusing it was clearly a win-win situation.

Although Southern California is not known for its abundant rainfall, on average there is enough to make rainwater harvesting a feasible solution for residential landscaping needs. The challenge is to provide enough catchment capacity—space—to adequately meet irrigation needs. From the combined talents of designer Marilee Kuhlmann, tank specifier Scott Mather, general contractor Danny Farkash, and automation programmer Blaine McNutt, emerged a one-of-a-kind cistern with state-of-the-art controls and data collection. The team was recently honored with a Rain Catchers Award from the American Rainwater Catchment Systems Association.

Many rainwater harvesting systems are designed to collect and store as much water as possible; creating a system based on actual irrigation needs is a fairly unusual approach, especially in a low-rainfall area. It would have been easier to rely on historical irrigation use, but the more relevant determinant was calculating the actual water needs of plants in the garden. The 7,500-square-foot tennis court, along with the roofs and other hardscape areas on the property, provides well over 63,000 gallons of water by capturing 14 inches of rain, the average precipitation for the region. There was adequate space to build a concrete cistern under an existing parking area where it is essentially invisible. Because of the fire-prone nature of the neighborhood, an additional benefit is that water in the cistern is also available to the Los Angeles Fire Department.

The location and other obstacles at the site made permitting and engineering the system a challenge, but the project became a model for the whole area. Collecting runoff at the low point was obvious, but water has to be pumped to the top of the property for irrigation purposes. Considering the slope of the garden and the distance the water needs to travel meant calculating the pumps and piping was critical.

A nondescript manhole cover is the only visible indicator of a 3,000-gallon Xerxes fiberglass tank installed under the driveway; yet access, when necessary, is only a pry-bar away. Water from the cistern is pumped to this auxiliary “day” tank that feeds directly into the drip irrigation system. The system only draws from the municipal water supply when no water is available in the day tank.

The construction of the concrete cistern was an unusual feat that required huge amounts of steel and concrete. Fortunately, the weather cooperated and not drop of rain was seen until the tank was completed. Three basket filters keep debris from entering the cistern and a “first flush” section was created to collect sediment not captured by the filters. As water fills this tank first, sediment settles out and clean water is transferred to the main holding area. Several hours after a rainstorm, sediment is pumped to a nearby planter so even the “dirty” water isn’t wasted.

A completely custom, user-friendly way of making the cistern and its components easy to monitor was developed by Blaine McNutt of SmarTek Pacifica. Accessible by any computer or smart phone, a custom-tailored app controls the pumps, constantly monitors water levels, and can even override the irrigation system. Almost every potential crisis was considered with redundancies for control over the mechanical parts should an emergency arise.

Status reports about the system’s performance are regularly emailed to the property manager. And when there is at least a 70 percent chance of rain and other specific parameters are met, the system automatically distributes water throughout the garden to make room for more input and to prevent runoff into the storm drain system.

This property’s very large garden called for a very large cistern that would be prohibitively expensive for most homeowners. But by implementing changes to increase efficiency and decrease water demand, as well as having a long-term, climate-appropriate garden plan, this residence is on the cutting edge of irrigation for the future. And the long-term data collected at

this site will be an asset to anyone in the residential rainwater-harvesting world.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses