Contributor

An attempt is being made to restore and preserve what remains of Burbank’s Farm in Sebastopol. Funds are needed for the work and donations, which are tax-deductible, should be sent to The Burbank Farm Restoration Project, Circuit Rider Productions, 9619 Old Redwood Highway, Windsor, California 95492.

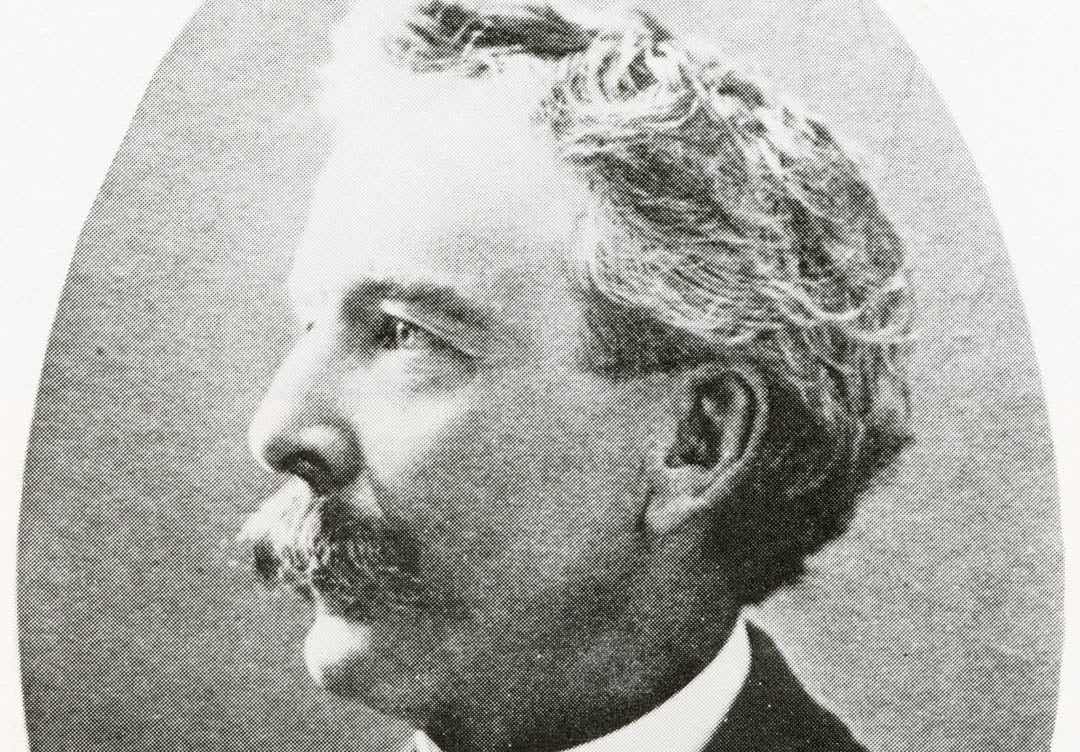

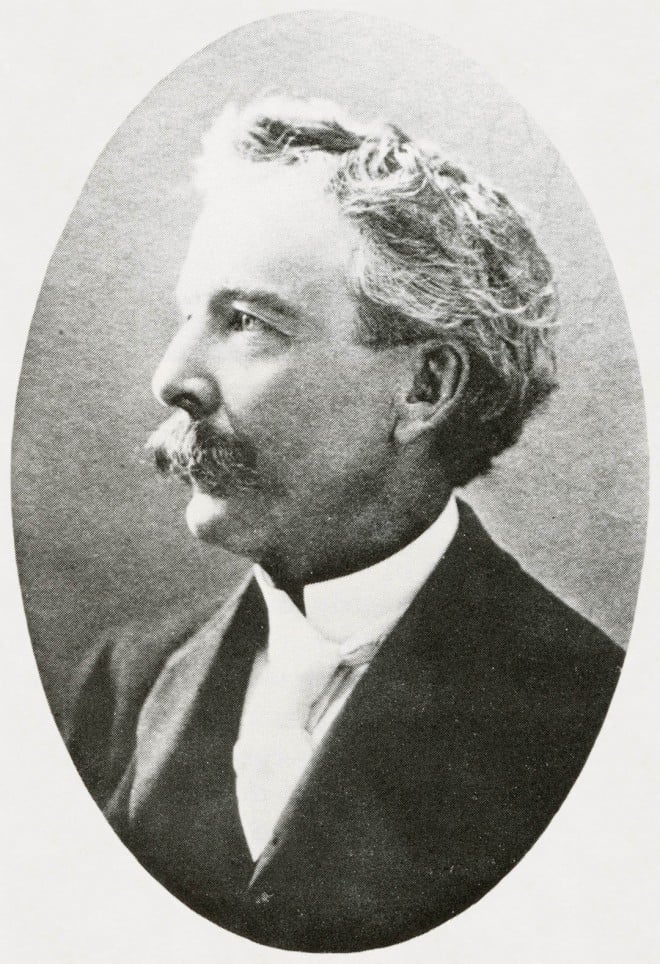

Luther Burbank (1849-1926), naturalist and staunch believer in the theories of Charles Darwin, left us an unequalled legacy of plants and insights into the field of plant breeding. His creations number over 800 and include some that are well known, such as the Shasta daisy, Burbank and Santa Rosa plums and Burbank potato, as well as many lesser-known fruits, flowers, vegetables and forage plants.

According to the historian Walter Howard, Burbank probably introduced more plants than any other American in history. His enthusiasm, determination and extraordinary success aroused a new interest in plant improvement and in that respect, his contribution is immeasurable. Like his friends Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, Burbank was a pioneer in his chosen field, and though his methods did not vary greatly from those of other breeders of his time, his results were phenomenal.

His success was primarily due to keen observation, his belief in the adaptability of plants, and above all, the exceptional size and number of his experiments. While other breeders applied genetic theory to their experiments and tried to forecast results, Burbank planted seedlings and made grafts by the thousands, from which only a small number were selected for introduction.

It is commonly thought that all of Burbank’s experimental work was carried out in Santa Rosa, California, where his home and small garden are now a National Historical Landmark, but the bulk of his experiments were performed at his Goldridge Farm in Sebastopol. This eighteen acre farm was vital to his success and fame.

Burbank’s breeding work began in his home-state of Massachusetts, where, as a market gardener in the early 1870s, he recognized the need for early maturing vegetables that would enable him to compete with other market gardeners. His first introduction, the Burbank potato, resulted from the rare find of a seed ball on an early rose potato in his garden. From the twenty-three seedlings it produced, Burbank selected one which later became the basis of a huge commercial industry in the Delta region of California, and after further improvement by others, in southern Idaho. In the early 1900s, the Burbank potato was adding $17,000,000 annually to the country’s agricultural productivity.

Rights to the Burbank potato were sold to an Eastern nurseryman, James Gregory, for $150. The agreement allowed Burbank to retain ten potatoes for his own production. In 1875, at age 26, Luther used the potato money to travel west where he joined his brother in Sonoma County, California. After working as a carpenter and at a Petaluma nursery for two years, he saved enough to start a small nursery in what he called “the chosen spot of all the earth as far as nature is concerned.”

The next few years saw several events that influenced Burbank’s future. In 1882, at the request of a skeptical but anxious customer who hoped to take advantage of a growing demand for prunes (the first transcontinental railroad had just been completed and dried fruits were being shipped east in quantity), Luther produced — from seed to budded trees — 19,500 prune trees in eight months. At that time, such a feat was considered nearly impossible and it gave him prestige and many new nursery customers. By 1884, the Santa Rosa Nursery was prospering and Burbank was able to purchase four acres near downtown Santa Rosa. This land, described by him as a “neglected, run-down plot which has been on the market for many years,” took many hours of work to make it usable. It was drained with tiles laid four feet below ground and amended with 1,800 wagonloads of manure.

In 1885, two important events occurred. The first, which launched his career and led to the developments on which his lasting fame was built, was the importation of a shipment of plums from Japan. Previously, only a few Japanese plums were grown commercially. The development of over one hundred improved plums by Burbank started huge horticultural industries in many parts of the world. With regard to Burbank’s work with plums, E.J. Wickson, Burbank’s contemporary and Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station at Berkeley, said, “One of the grandest contributions to the extension of the range of the plum in California was the introduction of the Asiatic species, Prunus triflora and Prunus simonii.” Both these plums were imported by Burbank. Wickson continued, “As with other fruits, comparatively few varieties of the plum are largely grown in California, and the list is continually changing by rejection of old varieties and introduction of new which are largely of Burbank origin.”

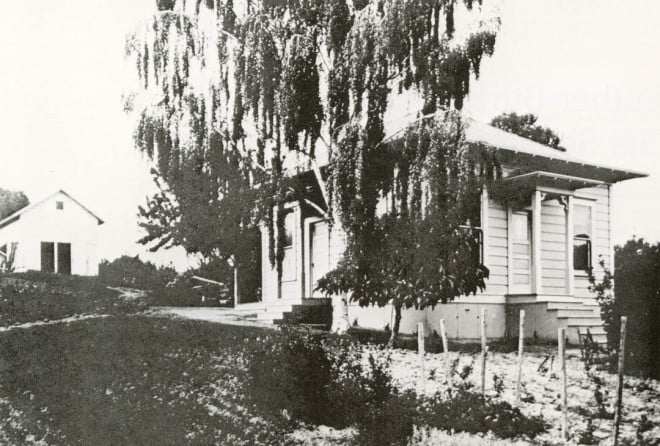

On December 28, 1885, eight days after the plum shipment was received from Japan, Luther purchased his Goldridge Farm; it was in Sebastopol, among the gently rolling hills seven miles west of Santa Rosa. This farm became the site of his experiments with the Japanese plums and enabled him to pursue his breeding work on the grand scale that had been his objective for years. As Burbank said, “With the development of the Sebastopol place, a new phase of lifework began.”

In its natural state, the Farm was covered with white and tan oaks, manzanita, madrone, hazelnut, Douglas fir, and a variety of herbaceous plants. The soil, undoubtedly an important factor in his decision to buy it, was dramatically different from the adobe at his Santa Rosa place; it was a sandy loam with several springs that seeped to the surface all year.

In 1888, in order to devote himself to his breeding work, Burbank sold his Santa Rosa Nursery. He still used the Santa Rosa garden to start most of his experiments, because there he had a greenhouse and irrigation. The experiments with annuals, which required constant attention, were carried out in Santa Rosa. However, his new fruits, nuts and perennials were tested and perfected at Sebastopol. In 1893, Burbank offered his first catalog exclusively of “New Creations in Fruits and Flowers.” During this decade, his productions were met with enthusiasm and he produced catalogs yearly. His reputation was at its highest.

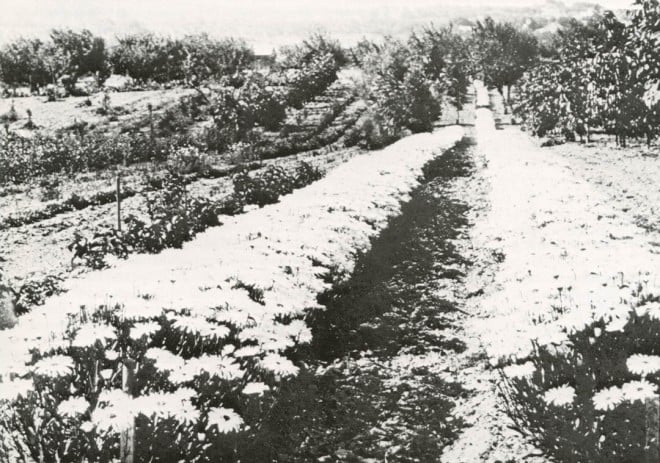

Burbank took the trip to Sebastopol several times a week in his buggy, or on his bicycle. Up until the early 1900s, he did all of his selection and roguing of unwanted plants himself, burning his rejects in enormous bonfires. As his fame grew and visitors became more numerous, his workers, under his instruction, took on the task of removing unwanted plants. Over two acres of lilies, watsonias, roses, gladioli, hawthorns, bottlebrushes, morning glories, poppies and sweet peas, and his daisies, in rows 700 feet long, set the Sebastopol countryside alive with their fragrance and myriad colors. Plants from all over the world were imported to the Goldridge Farm for crossing, testing and selecting. His fruits were better keepers, heavier bearers, and improved in size, color and flavor. Stoneless prunes (having only an almond-like kernel where a hard pit had been), apples, cherries, nectarines, pears and quinces were among the fruits improved at the Sebastopol Farm. Also developed there were hybrid walnuts, blight resistant chestnuts, thornless blackberries and white blackberries.

The plumcot, a cross of plum with apricot, though never a commercial success — it bore shyly and kept poorly — was, nonetheless, a remarkable accomplishment. Initially, a Japanese plum, Prunus triflora was pollinated with an apricot, Prunus armeniaca, and later the opposite cross was successfully made. Seed from these crosses was scarce, and most successful hybrids were from plum seeds. Eleven varieties were offered for sale in the early 1900s, each a blend of apricot and plum characteristics. Burbank’s success in hybridizing these two was disputed by other plant breeders, but similar crosses have been made and his claims are now accepted.

Creation of the Shasta daisy, an experiment that spanned seventeen years and involved hundreds of selections from hybrid seedlings of four species of Chrysanthemum, was largely carried out at Sebastopol where there was sufficient space for the many seedlings. The Shasta daisy, still popular eighty years after its introduction, was considered to be a new race of daisies, but according to Howard, the details of its ancestry are uncertain. The fact that it was developed through breeding and not purely selection was verified by Edward Wickson and Hugo de Vries, both of whom visited the Sebastopol Farm in the early 1900s, and saw Burbank’s work. Chrysanthemum maximum and Chrysanthemum lacustre were used, with another daisy now unknown, but the offspring of these lacked the whiteness of flower Burbank said “was to be one of the chief charms of my ideal daisy.” Chrysanthemum nipponicum was introduced into the crosses and selection continued for several seasons. In 1901 the first Shasta daisies were offered for sale. In 1904, three kinds, which he called ‘California’, ‘Westralia’ and ‘Alaska’ were introduced; ‘Alaska’ is still available.

By the early 1900s, Burbank had attracted the attention of many of the world’s scientific minds. Edward Wickson, who, in addition to being Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station, was Editor of the most influential horticultural journal, the Pacific Rural Press, became Burbank’s best promoter; David Starr Jordan, President of Stanford University; Liberty Hyde Bailey, Dean of the School of Agriculture at Cornell University; and Hugo de Vries, a Dutch botanist and Professor at the University of Amsterdam, were among those attracted to Burbank’s Sebastopol Farm.

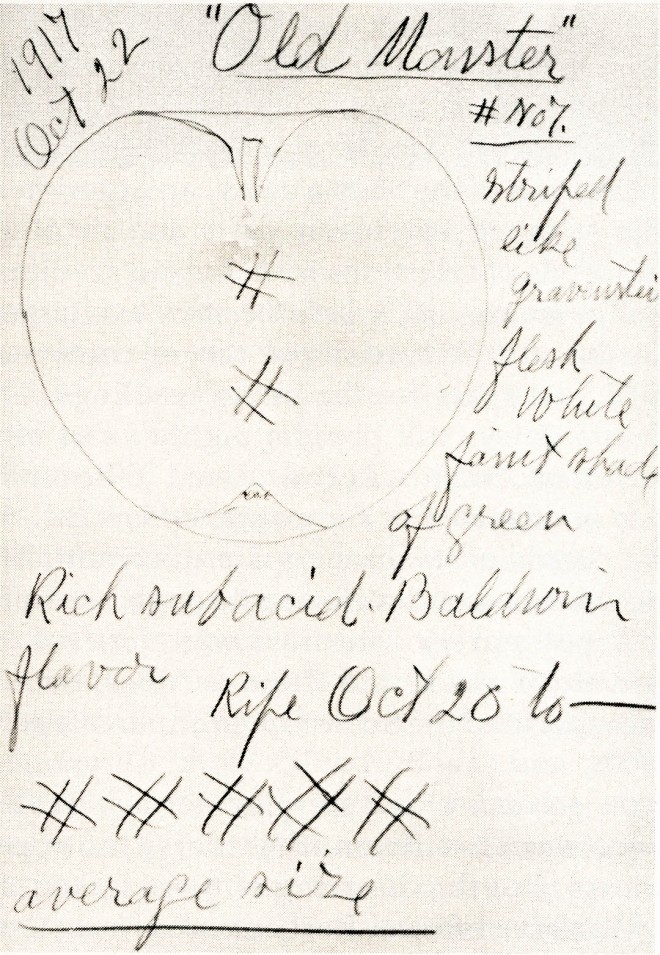

Burbank’s methods were simple. He was credited with having a keen eye for selection and a well-developed sense of the fruiting or flowering potential of a plant long before it reached maturity. In the selection of woody plants he is said to have chosen only those with large leaves and buds, and short stout internodes. Burbank’s intention in making crosses was to produce as much variation as possible in the seedlings. He had no interest in scientific controls, or in keeping accurate records of parentage; it was results he was concerned with. His records consisted primarily of personal notes and generally contained information on the potential economic value of a new plant rather than the steps needed to achieve it. For evaluation, new fruits were sliced in half, the outline traced onto paper and its quality assigned crosshatch marks. The more marks, the better the fruit.

In 1904, the then recently-established Carnegie Institution of Washington, though not usually supportive of such non-academic endeavors as Burbank’s, awarded him a grant of $10,000 a year for five years. It was agreed that documentation of Burbank’s experimental work would greatly benefit science, and the condition of the grant was that Burbank would allow someone from the Carnegie Institution to observe his work. George Harrison Shull, a biologist, spent part of each summer for two or three years with Burbank. Shull observed that Burbank’s methods consisted almost entirely of cross fertilization and selection. He noted that often no attempt was made to prevent self-fertilization or crossing with flowers of neighboring plants. Methods such as these were the cause of frequent criticism by scientific breeders and botanists. In the eyes of his academic contemporaries, Burbank’s experiments weren’t carried out under proper control.

George Shull said: “Mr. Burbank says himself that if he were conducting a scientific experiment he would do it differently, but maintains that it makes his work none the less scientific, indeed stamps it of a higher scientific type, that he arrives at the desired results without any unnecessary operation, thus allowing the accomplishment of a larger amount of work with the expenditure of a given amount of energy.”

From 1907 to about 1913, one of Burbank’s most actively promoted projects was his spineless cactus for fruit and forage. He believed the opuntias without spines could become an important cattle food in dry areas. The result of the work didn’t live up to his enthusiastic claims and his reputation suffered.

He sold spineless opuntias to dealers, who bought them mostly to resell, but unscrupulous ones among them mixed in regular opuntias from which the spines had been manually removed. There were unexpected problems in growing them which resulted in many disappointed customers. Plants were difficult to establish in arid areas without adequate irrigation. Cattle, finding the new cactus more palatable, ate it to the ground and killed it. Due to the high prices asked for spineless opuntias, Burbank was often left with stock that he was obliged to sell retail.

Hoping to relieve himself of these burdens, Burbank allowed two businessmen to take over the marketing of his plant creations. On April 22, 1912, the Luther Burbank Company was incorporated. The company went bankrupt after four years of fraud and misrepresentation of the Burbank name, much of it associated with the sale of the spineless cactus. Burbank took back the remains of his business, but devoted himself to growing and selling seeds until his death in 1926. Thus, although many had considered him a hero, the name Burbank was tarnished, and by 1918, according to Dreyer, Burbank was associated with the worst kind of horticultural quackery.

By the 1920s Burbank was a tired man. In 1923, at age seventy-four, he sold three acres of the Sebastopol Farm to a cemetery association. In an article that appeared that year in Henry Ford’s weekly paper, the Dearborn Independent, Burbank expressed his disappointment: “When I am tired I sometimes feel that if the world does not care if the best of varieties of plant life the earth has ever produced go to waste, I don’t care either… and they will go to waste unless somebody gives them the attention that I can no longer give.” Thus began the decline of the Farm and the loss of plants that continued until many varieties were gone forever.

Burbank’s life was nearing its end, and he was concerned for the future. Both Stanford University and the University of California seriously considered taking over the Farm, but money could not be found for it. In April 1926, before any plans to continue his work were completed, Burbank died. According to biographers Pat and Kenneth Kraft, Mrs. Burbank tried valiantly in the weeks immediately following his death to develop a plan for continued experimentation by employees and student assistants.

On July 6, 1927, Mrs. Burbank, then thirty-seven years old, announced that Stark Brothers Nurseries and Orchards Company of Missouri was taking over the operation of the Sebastopol Farm and the Santa Rosa garden. Stark Brothers, the oldest American nursery in continued existence, had already introduced several Burbank plants. They purchased the rights to complete experimental work begun by Burbank and the right to test, name and distribute plants perfected by him. Mrs. Burbank retained rights to two plants, the ‘Paradox’ and ‘Royal’ walnuts. Also included in this agreement was the exclusive right to use of the names “Luther Burbank” and “Luther Burbank Experiment Farm.” The contract with Stark ended the Farm’s history of experimentation, and the emphasis thereafter was on commercial production. At the time of the agreement, ten of the remaining fifteen acres of the Farm had been converted to apple orchard.

In 1927, Stark Brothers’ horticulturists began cataloging and evaluating the plants at the Farm. The new plant varieties thought to be most promising were sent to the Stark-Burbank Research Laboratories in Missouri and Illinois. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s trees were removed from the Farm as scion wood was sent for testing. The lease on the Sebastopol Farm continued until 1957, and the other provisions of the agreement were renewed until 1967. In the forty years of Stark’s agreement with Mrs. Burbank, over ninety Burbank plants were introduced, including the July ‘Elberta’ peach, ‘Elephant Heart’ plum and ‘Flaming Gold’ nectarine.

By 1965 the contract had been through three renewals and Stark Brothers Nurseries had paid Mrs. Burbank almost $75,000. The plant patent law of 1931 dramatically increased both Stark Brothers’ profits from Burbank’s work and the royalties paid to Mrs. Burbank.

In 1972, the Goldridge Farm was sold to the Sebastopol Area Housing Corporation, who built housing for the elderly on it. A condition of building was that three acres of the Farm that contains most of the remaining Burbank plants, be preserved. Preservation efforts are hindered by political conflicts over the property which is now prime real estate. The Western Sonoma County Historical Society, founded in 1975 to preserve the area’s historical resources, rekindled interest in preserving the Farm and, in 1978, was successful in getting the property listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

[sidebar]

References

Burbank, Luther and Wilbur Hall. 1927. The Harvest of the Years. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York.

Dreyer, Peter. 1975. A Gardener Touched With Genius; the Life of Luther Burbank. Coward, New York.

de Vries, Hugo. 1905. “A Visit to Luther Burbank.” Popular Science Monthly, vol. 67, p. 329–347.

Glass, Bentley. 1980. “The Strange Encounter of Luther Burbank and George Harrison Shull.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 124, No. 2, p. 133–153.

Kraft, Ken and Pat. 1967. Luther Burbank: The Wizard and the Man. Meredith Press, New York.

Wickson, Edward l. 1914. California Fruits. Pacific Rural Press, New York.

[/sidebar]

In January of 1980, in the midst of public controversy over the Farm, a citizens advisory committee was formed to plan for its future. In the meantime, the health of the plants and condition of the property had declined. It had been years since they were properly maintained. In the summer of 1980, aware of the need for renovation and maintenance at the Farm, Circuit Rider Productions, a Sonoma County non-profit agency specializing in land restoration and land management, spent three weeks clearing brush and pruning. In December of 1980, Circuit Rider began a special project, with a crew of seven, to continue this restoration work. Plants neglected for years have been rejuvenated. With the help of the plant inventory prepared by Stark Brothers, long forgotten plants have been identified and mapped. Though most of the commercially successful Burbank plants are gone from the Farm, evidence remains of Burbank’s attempts to change ill-flavored fruits into something useful. These include twenty-seven mountain ash trees and various hawthorns. Six trifoliate oranges, Poncirus trifoliata, of the twenty-seven that were there in 1931 remain. They are probably from Burbank’s experimentation with citrus in the 1890s. Catalina cherries, eighty-year-old hybrid chestnuts, solanums of unknown origin, a seedless persimmon as well as quinces, thornless blackberries, dwarf bamboo, blueberries, crinums, apples, plums and many shade trees have survived the years of neglect. A royal walnut, Juglans nigra x Juglans californica var. hindsii, one of the five original trees planted nearly 100 years ago by Burbank, still dominates the skyline along the western border of the Farm.

The Western Sonoma County Historical Society wishes to purchase the three acres. Several plans have been proposed for the future of the Farm. They include the establishment of a horticultural education center, but most importantly, the Farm will serve as a repository for Burbank’s plants that would otherwise be lost, and a living tribute to his work.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses