Contributor

- Topics: Archive

[sidebar]How small a part of time they share That are so wondrous sweet and fair!

Edmund Waller, from his poem, “Go, Lovely Rose”[/sidebar]

Fred Howard, who twice won the Gold Medal award for roses at the Bagatelle competition in Paris, France, before WW II, was among the most famous rose hybridizers in American history. An important nurseryman for many years in Southern California, he hybridized all kinds of plants in addition to roses. Yet, with a few exceptions, his work has disappeared from horticultural history; this is an attempt to understand why.

Howard was born in an old adobe house in Los Angeles on September 1, 1873, and joined a family of twelve, all of whom were avid plant lovers. Five of the children spent active lives in some aspect of the field of horticulture. He was educated at St Vincent’s College (predecessor of Loyola University) before entering, for the rest of his life, a successful career in the nursery industry. (The best source of information about him is found in the invaluable Southern California Gardens by Victoria Padilla, published in 1961 and reprinted in 1994.)

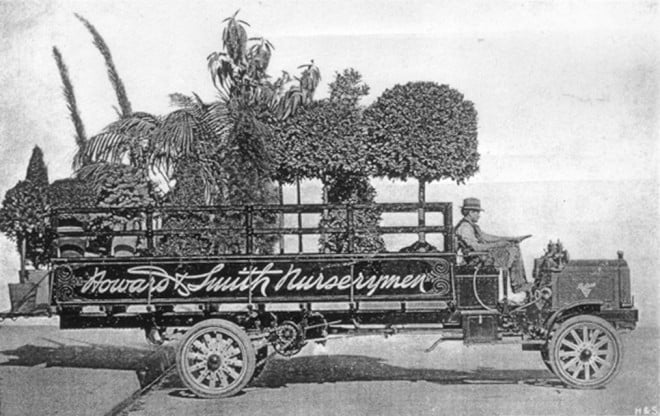

When only seventeen years old, in 1890, Howard opened his business with George W Smith, who had been living with the Howard family for some years and shared their enthusiasm for gardening. Their first nursery, in what is now downtown Los Angeles, specialized in flowering plants, especially cannas, dahlias, carnations, and geraniums. Ultimately, they grew hundreds of thousands of cannas at their final nursery site in Montebello, where they had moved in 1905, on thirty acres that had previously been used as their growing grounds. Howard bought out Smith in 1914.

As the business grew, Howard increased the list of stock until they were shipping plants all over the US, including two million roses each year. His interest was mainly in propagation, and Padilla states that his “plants number well into the hundreds,” especially the gerberas, cinerarias, verbenas, cannas, amaryllis, and primulas. His bigeneric hybrid, xAmar-crinum howardii (now called xAmarcrinum memoria-corsii), a cross of Crinum moorei and Amaryllis belladonna—an extraordinary triumph—was awarded the Cory Cup by the Royal Horticultural Society.

Rose Introductions

International recognition for his roses came early in his career; in 1918, he entered his hybrid tea ‘Los Angeles’ in the Paris competition and won the gold medal. That rose is still in commerce today: a coral pink with a gold base, large double blooms, and an intense fragrance. He received another gold medal, three years later, for ‘Miss Lolita Armour’, also a hybrid tea; this rose has completely disappeared from the trade and no longer appears in any collections.

His next rose to maintain its fame to this day is ‘The Doctor’, named for Dr J Horace McFarland, the prime mover in the American Rose Society at the time. Released to the trade in 1936, it received an award from the Royal National Rose Society and several awards in the US. One of its parents is his 1918 winner, ‘Los Angeles’. A bushy hybrid tea with satin-pink flowers and a strong fragrance, I remember bouquets of this in my childhood home in Los Angeles.

My mother was an avid rose grower, and, in 1938, when I was a teenager, my father drove us to Howard’s Montebello nursery so my mother could see the collection. She bought his new rose, ‘Will Rogers’, named for the famous entertainer and movie star, who had been killed in an air crash in Alaska that year. Two nurseries still offer ‘Will’. My mother eventually eliminated it from her garden because the flowers burned in the summer sun.

Rosa‘California’, first offered in 1916, was later withdrawn from the market. Howard states in a newsletter in 1940, “It was a splendid yellow of a deep golden shade, but the plant lacked vigor of growth. So I destroyed the entire stock.” He kept the name for a future introduction and grew thousands of seedlings “until at last one lovely yellow appeared that, after exhaustive tests, I felt worthy of bearing the name.” The famous English hybridizer, David Austin, has done the same thing with several of his early introductions, removing weaker ones from production and re-using the name for a better rose later.

His last successful effort to stay in the rose race was his ‘California Centennial’, a hybrid tea that celebrated the anniversary of California’s 1850 admission to the Union. A shrub with pointed buds and deep red petals, the original descriptions stated that it had a strong fragrance, but my flowers have little. A few nurseries still offer it, and I have seen it in several public collections. The California State Assembly designated it as the official State Rose, two years after Howard died at seventy-five on July 15, 1948.

Howard offered over one hundred of his own roses over the years, yet only ‘Los Angeles’, ‘The Doctor’, ‘Will Rogers’, and ‘California Centennial’ have survived. In a 1938 report in The American Rose Annual, nearly thirty of his roses were evaluated, receiving mixed reports from growers and nurseries. Most of his introductions were hybrid teas, but a few were polyanthas, none of which exist today. Other famous hybridizers are on the list in the 1938 report: Brownell, Hill, Nichols, McGredy, Mallerin, among others. They, too, offered many roses that have since disappeared from the nursery trade.

Survival of the fittest has been the pattern in the world of plant breeding, particularly since WWI, when the hybrid tea became the rage. Nurseries released hundreds of plants before they had been properly tested (note Howard’s remark above); after a few years, these cultivars faded away. Howard’s efforts were valiant, but most of his roses lacked the stuff of immortality. Today, such stories are still common in the rose trade.

The author would like to thank Marlea Graham, editor for the California Garden and Landscape History Society, for her great help in researching this article.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Welcome, Greywater, to the Garden

Summer 2022 Oh, summer: delightful warm air, tomatoes swelling on the vine, fragrant blooms on an evening stroll. When it’s warm and rainless, how is

Big Tree-Data and Big-Tree Data with Garden Futurist Matt Ritter

Summer 2022 Listen to the full Garden Futurist: Episode XV podcast here. We are in an environmental crisis right now in many parts of California

Responses