Contributor

- Topics: Archive

This article has been adapted from the second of a pair of garden design talks presented at the 2005 San Francisco Flower Show. The first talk, appearing in July, 2005, explored the relationship between the design of garden spaces and the kinds of behavior and movement patterns that different spaces are likely to promote. This second considers how we might design gardens to evoke particular emotional responses. Both talks were intended to provide useful guidelines for garden design but were not meant to offer a foolproof and definitive design process.

Have you ever asked yourself “How would I like visitors to feel when they come to my garden?” Let me adjust the emphasis in that simple question: “How would I like visitors to feel when they come to my garden?” Indeed, have you ever asked yourself how you would like to feel when you step out into your garden?

It is surprising how few of us have imagined our gardens in this way. The problem, of course, is that most of us are so busy mowing, weeding, watering, planting new plants (which we couldn’t resist buying even though we knew we didn’t have room for them), or, as a result of years of excessive planting, perpetually hacking back vigorous growth. In other words, we are so busy dealing with our garden’s needs that we rarely have time to think about our own needs and experiences.

By exploring the meaning and purpose of our gardens from the perspective of our feelings, I hope to avoid the usual stock answers to questions about the purpose of gardens. Such responses, which we might describe as “off the shelf,” include: I want to get away from it all. I want an escape. I want a retreat. I want rest and refreshment. I want flowers year round. And so on. While some might want to be alone, others crave the opposite and want gardens that are conducive to conversation, places to entertain friends.

On a more practical note we may want our gardens to be places where kids can run wild, get their hands in the mud, climb trees, whack bushes, and generally come into the house at the end of the day exhausted but exhilarated. More prosaically, we may simply want a fenced space for the dog. Notice how these answers shy away from feelings toward uses and activities.

Accommodating uses and programming space is a normal way of thinking about design, but I want to explore garden settings designed to evoke particular moods or feelings. “That’s preposterous—you can’t design experiences!” True enough, but, in a garden, you can not avoid having experiences. Design decisions and garden experiences are related; here, I explore garden design from an experiential perspective. I do not intend to give definitive directions about the experiences you should accommodate in your garden; clearly that is a personal choice. But, I will suggest ways of thinking about how to evoke desired emotional responses.

This approach is worth our consideration for two reasons. First, it provides an experiential focus for garden design as an antidote to the over-intellectualizing so readily induced by paper and pencil or computer-based design—design methods that inevitably favor mental ideas and sight over other senses. Experiential approaches remind us that gardens engage all the senses—they are sensory feasts, not merely visual meals or mental snacks. The second value of this approach is that it encourages us to view familiar situations from new perspectives. In design, as in life, there is nothing more salutary and revealing than seeing the familiar in a new light. “Oh my gosh! Look at that!”

So, what do we want our gardens to feel like? How do we want to feel as we enter, pass through, spend time in, and then leave our gardens? Before addressing these questions, let me emphasize that this is a perceptual exercise, not an alternative design method. It is a technique that stretches the mind, gets us in mental shape, and creatively explores ideas. It is not a substitute for analyzing your garden site and the activities you wish to accommodate in it. It is a process that jogs our minds out of their familiar tracks and, in so doing, enriches our design explorations.

I hope that the title, “Gardens that take your breath away and give it back,” captures the tremendous excitement of this way of looking at design, its potential to quicken the pulse, and catch the breath—to affect inspiration and expiration.

Student Responses

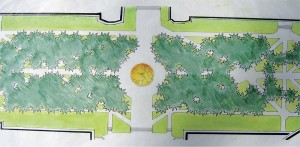

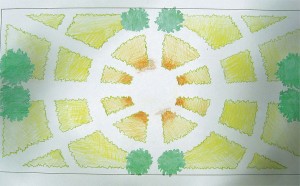

Garden design articles are usually accompanied by images of gorgeous gardens, from all corners of the world, full of plants at their peak of perfection; in other words, impossible situations that are nothing like the reality of almost all of our gardens, most of the time. I have chosen a few illustrations produced by University of Washington students in response to an impossible assignment: they were asked to redesign a flat, four-acre quadrangle in the heart of the university campus, using only plants and paths in such a way that someone walking through the quad would experience a prescribed emotion. These ranged across a wide spectrum from joy to bewilderment, boredom to seduction, rage to awe. I have also included a few photographs from Seattle’s incomparable Japanese Garden in Washington Park Arboretum. These photographs not only pay homage to beauty but suggest that we may find, all around us, instructive examples of how our environment affects our emotions.

The genius of the question assigned the students is confirmed by the genius of the answers. It is a question that lacks prescribed answers, handy reference books, or authority figures to consult. It is a question for which there is no right answer—not even a right approach. Nevertheless, year after year students created innovative and thoughtful designs using the only source available to them—their own experiences and their own understanding of how the physical world influences their emotions. The question inevitably becomes: what sorts of spatial experiences and plant characteristics would evoke this emotional response in me? And would my response be typical of the rest of humanity?

Emotions

To address our question I begin with the proposal that some emotions develop not all at once, but over a period of time, and require sequential experiences to evoke them, whereas others may be evoked in a single space. We may describe these emotions as spatially dynamic and spatially static.

In general, I suggest that spatially dynamic emotions respond to sequential changes in space, and that spatially static emotions respond primarily to the characteristics of a single space. For example, it is hard to imagine how we might evoke ‘anticipation’ or ‘expectancy’ without moving through space, while ‘calmness’ and ‘peacefulness’ suggest repose and thus a static viewpoint in a single space. These categories are independent of the desirability of the emotional responses. For example, a sequential experience could also induce bewilderment or confusion, and a single space could induce boredom or dullness—all responses we are unlikely to wish to induce in our garden visitors. In addition to looking at positive emotions, however, it is important to consider negative ones to learn what not to do spatially.

Spatial Sequence and Movement

Movement through a garden or landscape necessarily involves passing through a sequence of spaces, whether or not these were considered when the garden was designed. Where spaces and their surrounding plants are all similar, the resulting sequences emphasize continuity and coherence. Where spaces and plants change significantly, the sequences emphasize variety and change. When sequential variety is ordered in a comprehensible way—which we typically describe as “rhythm”—we have an ordering system that may combine continuity and variety in complex but legible ways. If we are unable to discern any order to sequential variety, the result is chaos and confusion. Each expression of spatial sequences results in different emotional responses.

Let us examine a few examples to suggest the range of possibilities. Emotions such as anticipation, expectancy, and surprise are particularly easy to evoke by means of sequences of space and plants. To elicit these responses, one might design a series of spaces of contrasting sizes or use plants with dramatically different characteristics to make each part of the garden distinct and different. This could be as simple as differentiating between the shapes of space and types of plants in a side and rear yard, so that coming round the corner of the house might be a delightful surprise.

We might create rhythms that build up to a crescendo, using a spatial sequence wherein plants become increasingly complex and spaces become larger and grander. If successful, visitors may respond to this climax with feelings of awe, fulfillment, or thrill. However, if we don’t effectively control the design parameters of the sequence, then spatial forms and plants may appear to succeed each other randomly, and the result might be feelings of restlessness, mystery or, worse still, bewilderment. Such responses are likely to be confirmed in our minds if sequences lack perceptible terminations or destinations. In extreme cases of randomness, we may discern no order to the spaces and plants, and we find ourselves, in Shelley’s words, “When the dreamer seems to be,/Weltering through eternity.” If the perception of sequence devolves into random, meaningless changes (a condition coming soon to suburban sprawl near you), we are likely to respond with emotions such as uncertainty, confusion, disorientation, and intimidation. In other words, when we design sequential spatial experiences, it is important that they do not seem to negate the purpose and value of movement. If they do, they will appear, as Macbeth puts it, to be “a tale/Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,/Signifying nothing.”

In contrast to sequences full of variety and change are sequences that display minimal change or development, perhaps all of a similar size and with similar plants. They emphasize continuity of experience rather than contrast and variety of experience. If the repeated spaces and plants are positive, they may provide gentle and reassuring satisfaction; if negative, a mind-numbing boredom may result.

Path sequences that thwart desired movement patterns, or that offer a goal and then willfully direct users away from it, should be avoided unless we are confident that users have willingly consented to submit to our manipulation. It is surprising how frequently designers mistakenly make this presumption to justify their designs. When a positive and engaging sense of mystery tips over into disorientation, we have gone too far. Where sequences of movement conflict with the desires of users, they may respond with frustration, aggravation or, if they suspect that the thwarting of movement is deliberate, with anger or rage.

Manipulation of Space

Some emotional responses are most effectively aroused through manipulation of movement patterns and spatial sequences; others are relatively independent of movement or may best be evoked from static viewpoints. In such situations, we don’t have the tool of sequential experience to work with and must rely on the shape, size and character of spaces—which is to say the character of surrounding plants—to evoke the mood. Think, for example, of calmness, peacefulness, quietness, and serenity; we can imagine designing for these either in gently reassuring sequences or in singular, unified spaces. These moods don’t necessarily require large spaces; with clever and thoughtful manipulations, they may be evoked in a tiny patio. Positive emotions that might be effectively evoked in a static and relaxed observer—thus, in a single space—include restfulness, contentment, and relaxation. If we find ourselves slumped in a chair in a drab or ugly space, however, unwilling to rouse ourselves, feelings of dejection, melancholia, sadness, and despondency might result.

Emotions that seem to require lots of room—or to be more accurate, the perception of spaciousness—include expansiveness, freedom and exhilaration. Emotions compatible with confined spaces may include contentment and reclusion. In these cases, we may employ color, texture, pattern, and light conditions to influence the perception of space. We may also manipulate spatial form to affect the perception of spatial extent. For example, a sense of expansiveness may be induced in a relatively small space by implying that the space continues around a shrub mass or by ‘borrowing’ distant scenery.

The fact that we have difficulty forming mental pictures of complex spaces may cause them to induce feelings of intrigue, frustration or anxiety. By contrast, spaces with simple, clear, and comprehensible shapes are more likely to promote feelings of restfulness and relaxation than spaces with convoluted or ambiguous forms. Thus, the degree of “clarity” or “definition” of space is an important variable to

consider and leads directly to our next topic: the contributions of the forms of plant masses and plant characteristics to emotional responses.

Plant Characteristics and Plant Masses

At this point, even the most attentive and charitable reader may have interpreted my focus on garden spaces to mean that I think plants are less important in evoking emotional responses than spaces. Nothing could be further from the truth: plants are the primary material that shape and enclose garden spaces, and it is their characteristics (along with light and shadow) that give character to a space. Therefore, to consider the feelings that gardens evoke, we must consider plant characteristics and the forms of plant masses, as well as space and movement patterns. Let us consider emotional responses that seem to derive more from the character of plants and spaces than from the shape or form of spaces. Again, these may be positive or negative responses.

If, for example, one wished to draw forth elation, ecstasy, or euphoria, one might select plants with light or bright foliage and flower colors, arrange them in rich and vibrant patterns, and shape the masses to allow brilliant sunlight to pour into the spaces. If one wished to evoke a sense of dejection, melancholia, or the blues, one might do the opposite and use dark and somber plants, arranged in dense, heavy masses that dominate space and admit only a pitiful light. I hasten to add that this is not an endorsement of such practices, but we all know places that exhibit such characteristics (hopefully, not our own gardens).

Some emotions seem to require the light and exuberant growth of annuals or perennials rather than the more stolid forms and growth of woody plants. Think, for example, of vivacity, cheerfulness, liveliness, and felicitousness—surely emotions we sense when holding packets of seeds in our hands on a bright spring day! Such emotions seem to need comfortable weather conditions—uninhibited spring and easeful summer—suggesting the limit of our ability to design for emotions. For, it must be confessed, many emotional responses may depend on flowers or other passing characteristics of plants or weather and, thus, are strictly seasonal: July’s euphoria may be February’s dejection.

Limits of the Approach

Let us imagine one last grand flourish of emotions. How might we design gardens to evoke a sense of intoxication, sensuousness, or seduction? Surely such emotions remind us once more that gardens affect all the senses: smell, taste, hearing, and touch as well as sight. If we set out to design seductive gardens, the result would be infinitely more appealing than the scalped lawns dotted with shrubs pruned to within an inch of their lives (common fare, today, in suburbia). But there are, of course, limits to this way of thinking about design. Although it may help us to create better designs, we should not presume that, if we design with one emotion in mind, visitors will inevitably experience our garden that way. Garden experiences are a good deal more complex and less controllable than I may have implied, and that is part of their delight (no delight without dilemma).

This becomes painfully apparent when we consider emotions such as sublimity, immanence, and transcendence. Indeed, I would never have presumed to ask students to consider such emotions were it not for the fact that the English Landscape School spent well over a century exploring the possibilities of ‘the sublime.’ Even though we are on ethereal ground when we try to describe spaces, sequences, and plant characteristics that might evoke transcendent experiences, students nevertheless produced startlingly original and evocative designs. Their designs made thoughtful connections between physical reality and transcendent experiences, suggesting that this approach is effective at taking us away from cliché-ridden ways of thinking about gardens and design. Why not try to search out the sublime in our own gardens?

In conclusion, I return to my title and the idea of creating gardens that take your breath away—that catch you and evoke awe, surprise, delight, or whatever breath-taking emotion works for you—and give it back, allowing you to inhale and exhale long, deep, contented breaths—relaxed, easy, and restful breaths. But not for long! For, surely, you will find yourself one sunny morning turning innocently to your significant other and enquiring, “How would you feel about ripping out the lawn and putting in a mass of Felicia or pink petunias?” Will he or she sense that what you mean by that question is: “How would you feel about this?” “Would it send a shiver down your spine?” “Would it prompt a feeling of elation or bewilderment?”

Finally, some marching orders. This approach makes you the expert. Your decisions will be based on your feelings and your responses. If you follow your creativity, no expert from out of town will be able to show up at your front door and say, “You’ve got to be joking! That’s not fulfillment you’ve got there, that’s frustration—and a pretty severe case of it, too,” because you will know that, for you, it is fulfillment, and, with a confident smile playing across your face you will point the expert off down your carefully contrived garden path to be enveloped by the mystery and intrigue that lie around the corner, never to be heard from again.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses