Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Other than spiders, perhaps no other animals in the garden engender as much fear and misunderstanding as reptiles. Once safety has been ascertained, however, the curious gardener may draw near to appreciate our scaly allies who keep many garden pest populations under control. Garden reptiles are known to eat insects, spiders, slugs, and even larger garden prey such as rodents.

We used to think of reptiles as cold-blooded, but they are more properly called ectotherms, deriving their temperature from the environment rather than internal processes. Reptile body temperatures vary; for instance, alligator lizards maintain a higher body temperature than most other lizards, allowing them to be more active in cooler weather and to prey on other reptile species. Some ectotherms are able to maintain even higher temperatures than some warm-blooded animals, called endotherms.

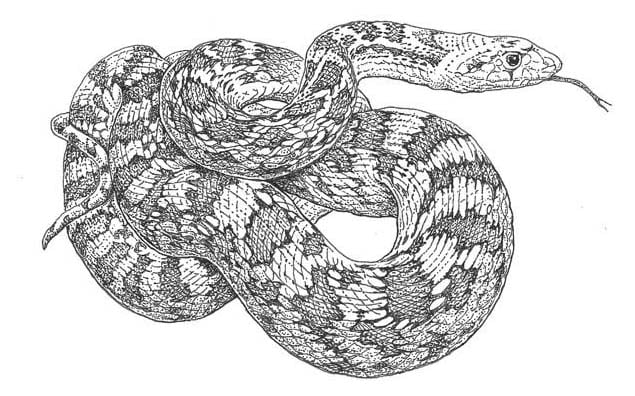

Reptiles commonly found in Western gardens include several species of snakes and lizards. Of these, the only ones that are potentially dangerous to humans are rattlesnakes (Crotalus species in the Western US); should you find one in the garden, it may be time to call a reptile rescue organization for a relocation service. Gopher snakes (Pituophis catenifer) are often mistaken for rattlesnakes, but are distinguished by the lack of rattles and a slimmer head. The gopher snake’s habit of flattening its head and vibrating its tail when threatened emphasizes the similarities and has cost many a beneficial, rodent-eating gopher snake its life.

Garter snakes (Thamnophis species) are common Western garden residents, especially in gardens that are near streams or swampy areas. Depending on where they are found, they may exhibit a variety of coloring, but are almost always striped longitudinally, a useful camouflage for slithering through the grass. Recently, I was fortunate to come across two ringneck snakes (Diadophis punctatus) as I cleaned up a long-abandoned corner of my new garden. Although these small and graceful snakes are harmless, when disturbed they coil up to reveal a bright orange underbelly and may emit a fetid chemical that clings to the skin long after the snake has been released.

Occasionally seen in gardens, kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula) principally prey on reptiles, including rattlesnakes, although they also eat rodents, birds and frogs. While several color morphs exist, the most commonly seen in the Western US is a distinctive chocolate and white banding. They are immune to the venom of rattlesnakes, and I was once privileged to observe a kingsnake eating a young rattler, something I remember every time I see one in the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden where kingsnakes are a relatively common sight.

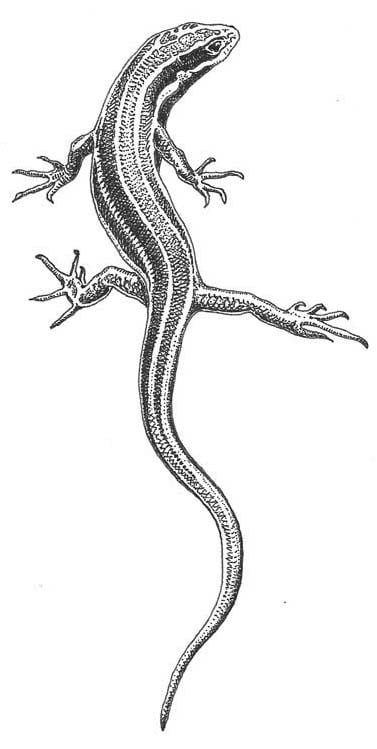

Many gardens do not harbor snakes, but suitable habitat is easily provided for lizards within their range. Explore a woodpile or heap of rocks and the gardener will almost certainly turn up a lizard. In the same for- gotten corner where I found ringneck snakes, I also came across the neon-blue flash of a young Western skink (Plestiodon skiltonianus) as it escaped into the safety of the leaf litter. Skinks are distinguished from other lizards by their short limbs and thick necks, which lend them a snake-like appearance. As they mature, they lose the beautiful azure blue that is so striking, but breeding males develop orange patches under their chin. Like other garden lizards, skinks eat a variety of insects, pillbugs, snails, and other invertebrates, and can detach their tails which then thrash about and presumably distract hungry predators.

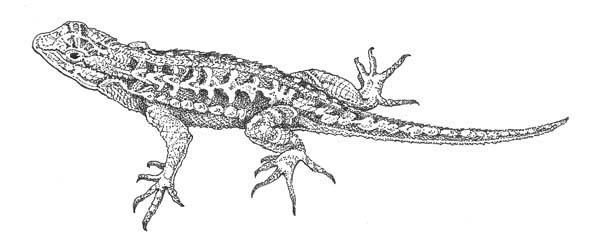

Coming across a full-grown alligator lizard is startling. They can be over seven inches long—and that doesn’t include their long tail. Alligator lizards (Elgaria species) can be active at lower temperatures than most other lizards, and are effective predators of skinks and other lizards in addition to spiders, snails, and insects such as crickets and grasshoppers. Although they are diurnal, they are rarely seen basking in the sun like other lizard species, and in hot climates, they may take cover during midday.

The Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) is the common lizard with the bright blue belly often seen basking on rocks in the sun. Males may occasionally be seen doing “pushups” to impress nearby competitors. The abundant blue-bellies in the Santa Barbara area attest to healthy insect and spider populations, on which these lizards thrive. A little known benefit of Western fence lizards is a protein in their blood that kills the Lyme disease bacterium carried by ticks; consequently, the incidence of the disease is lower in regions where these lizards are found. Leaving my home on summer mornings, I observed one fellow that always seemed to be waiting expectantly in the same spot. The mystery was solved when I learned that a neighbor enjoys hand- feeding resident lizards with pet-store mealworms.

What a pleasure to have wild insect-eating pets!

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses