Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Most gardeners are enthusiastic in welcoming beneficial insects to their gardens. Lady beetles, lacewings, and even bees of all stripes are enthusiastically encouraged to take up residence. But bring up the advantages of hunting wasps prowling about the garden, and generally, there is a long pause. However, consider this: while bees provide us with pollination services and honey—a critical and delicious contribution—hunting wasps help control populations of pest insects in gardens.

The hymenoptera, which include bees and ants, are incredibly diverse in form and life history. Wasps have chewing mouthparts, and a life cycle of complete metamorphosis; their larvae are grub-like or maggot-like. The female ovipositor is often well developed, and may function as a stinger. Many insects mimic the formidable stinging wasps—among them flies, beetles, and butterflies. In common with most other hymenoptera, unfertilized eggs develop into males, while only fertilized eggs develop into females.

Differentiating between parasitoid and hunting wasps is not always clear. Nature being what it is, the boundaries between parasitic and hunting behaviors are sometimes a bit vague (see “Garden Allies: Braconid Wasps” and “Ichneumonid Wasps” Pacific Horticulture issues Spring 2008 and Spring 2013 respectively.) For our purposes here, we define hunting wasps as capable of carrying off their prey to their nest. For those interested in subtleties, a fascinating read is Bees, Wasps, and Ants: The Indispensable Role of Hymenoptera in Gardens, by Eric Grissell (Timber Press, 2010).

Most wasps are carnivorous, at least in the larval stage. Many adult wasps either supplement their diet or feed exclusively on nectar and sometimes honeydew, the sugary waste product of insects such as aphids and scale insects. In a sunny floriferous garden, wasps are often seen visiting flowers in the carrot and daisy family. Gardens with a generous complement of native plants host many of the herbivorous species that wasps hunt and contribute to a healthy ecosystem that includes birds and reptiles.

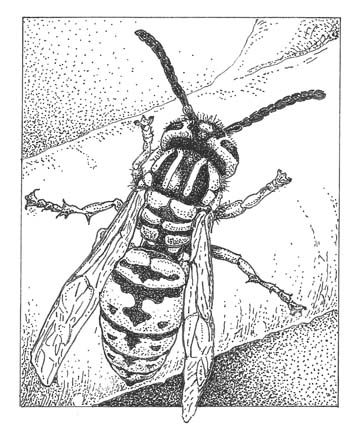

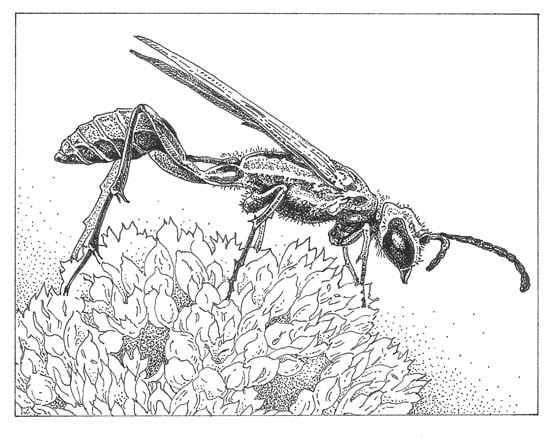

The hunting wasps that provision their nests with prey for their larvae are broadly divided into two large groups. Solitary hunting wasps are generally non-aggressive, while social wasps can be aggressive when protecting their nest. Two of the largest and most common groups of hunting wasps that are seen in gardens are the family Sphecidae, solitary wasps that include mud daubers, thread-waisted wasps, and sand wasps, and the family Vespidae, which encompasses the familiar colonial wasps such as hornets, paper wasps and yellowjackets.

Sphecid species vary in size from very small to some of our largest wasps. Most are ground nesters, while some nest in hollow plant stems, existing holes in wood, or build mud nests. Although they are solitary, each female provisioning its own nest, they sometimes nest in aggregations. Some sphecid species only prey on specific arthropod species, but many have a more general diet. Prey includes species of lepidoptera, diptera, coleoptera, hemiptera, orthoptera, hymenoptera and spiders.

French naturalist Jean-Henri Fabre elucidated the behavior of solitary hunting wasps in the late 1890s. A born observer, he studied insect behavior at a time when most entomologists were occupied killing and classifying insects. Fabre did not accept evolution, and was guilty of anthropomorphizing in his writings (a big no-no in the world of science). However, his eleven volumes on the life of insects (English translations are readily available) captured the public imagination, and brought him high honors including a nomination for a Nobel Prize. Many of his studies are still useful today.

Stinging wasps may be a nuisance in some circumstances; generally, the social vespid species are the culprit, although “pest” may be too strong of a word for many of these beneficial pest-eating insects. Like social bees, vespid colonies include queens, workers, and males, but unlike bees, these only last for a single season. Before eliminating nests, confirm that they are in a hazardous location. There is no denying that the ground-nesting yellowjackets, despite their prodigious hunting habits, are considered by many to be a pest species, as any picnicker can attest.

Like the sphecids, the vespids prey on a variety of arthropods to provision their nests. The common paper wasps, whose nests are often found under the eaves of houses, prey on caterpillars, a useful garden service! The bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata) builds its fabulous football-sized nest in trees or shrubs; adults prey on yellowjackets and flies. A recent gift to the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, a bald-faced hornet nest (abandoned by its occupants!), has been fascinating for visitors, who discover, as they examine the striped outer covering, that it is not humans, but wasps, that invented paper.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses