Contributor

- Topics: Archive

What small-scale living means to one Bay Area gardener.

The space I occupy under roof is a mere 350 square feet, but the space I live in is infinite. Recently, I discovered that the neighbors refer to my studio as “the glass house,” most likely because the top of a twelve-foot-high window above the indoor-outdoor fireplace is what casual passersby see from the street. I like the glass house description, because it captures the sensibilities of living on a small scale without feeling martyred. There’s a fine line between embracing an aesthetic life and a monastic one.

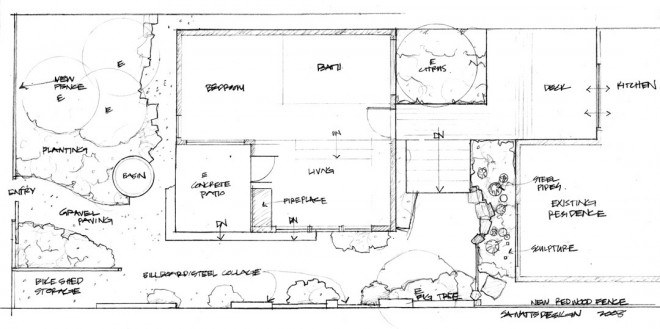

Three years ago, I sat down with an architect whose green credentials were evident in his portfolio and whose enthusiasm for small space design was infectious. At the time, I was living in an 800-square-foot former earthquake cottage in San Francisco that sat on the back end of a typical city lot (twenty-five feet wide by one hundred feet deep). The most valuable part of my little homestead was the land in front of the house—land on which the City would allow me to build. And so began an adventure that culminated in a studio pavilion surrounded by a garden that feels as much a part of my living space as my bedroom and sitting area.

The context for this migration from earthquake cottage to studio begins with a mother’s conceit. My children had graduated from colleges back East, where they had grown up, but both expressed interest in relocating to the Bay Area. Because the high cost of housing is the most prohibitive part of living in San Francisco, I reasoned that putting an addition on the cottage and creating a separate space for me would entice them to move here and, at the same time, provide them with ready-made housing. We would maintain separate households, thereby preserving the integrity of our private lives, while sharing a kitchen, laundry, and outdoor deck. Good plan. That they did not follow this script is now beside the point (of the plan). An architect was secured, concepts were created, permits issued, and lots of glass ordered.

Small-scale living is not for everyone. At social gatherings, I am keenly aware of the need to not become that boorish proselytizer who carries on about the moral probity of living with less. The ability to downsize still confounds me, but it is where I am most comfortable. “It just suits me,” is how I respond when pressed. I was fortunate to pair up early with an architect, David Winslow, and a landscape designer, Shirley Watts, who were able to translate my ideas into a viable living space and lifestyle, and whose own sensibilities fed and enhanced their separate creations. The talents behind the studio and garden were a fortuitous convergence of these two professionals, each happily burdened with creative spirits and deep feelings for small-carbon-footprint living and the need to repurpose the cast-offs of others.

On a rainy morning, I open the door of the studio to hear and watch the rain falling from the gutter extension into the pond, ten feet below. The pond was not my idea, but, after the bike hut (which was), the pond is the garden feature I most enjoy. Truth is, such observations don’t always hold, and I resist the temptation to issue an ordered list of garden favorites, simply because they change from season to season. Sometimes, it might be a specific plant. Other times, I find myself staring through a four-foot portion of the recycled metal fence, which has created a moiré fabric effect against the neighbor’s patio. When I am finished with this study, my attention moves along to a bright yellow remnant of a recycled vinyl billboard that bears, of all things, a photo of London’s Big Ben with a pair of probing eyes superimposed next to it. These repurposed elements are framed by vertical portions of the original wood fence, which conveniently blew down during construction.

Details Are Critical in a Small Space

As the studio building emerged and the garden design evolved, I was fascinated by the way both David and Shirley worked together, yet separately. Shirley first visited the site when the studio was approximately sixty percent complete. Taking cues from the already rusting Corten steel siding that wrapped around the bulk of the studio, and from the use of simple materials such as the polished concrete floors, glass, and reclaimed lumber, Shirley began assembling a stockpile of treasures from recycling and salvage centers. I would arrive home at night to find lengths of iron pipe that would eventually host French tarragon, mint, thyme, and a variety of impossible looking succulents. Tall, slender stainless steel poles, whose previous origins and purposes still elude us, now reign as a grove of shiny standins among the three slender trees that barely survived the construction phase. “I just liked them when I saw them,” is how Shirley explained the poles’ presence. Odd and crippled lengths of rusty rebar prop up plants whose enthusiasm for growing tall eclipsed their ability to support themselves. Some of the rebar sisters occupy a space of their own, implying a hint of rebellion and a reminder that there is beauty to be found in unlikely things.

I once characterized the garden as flowered urban funk, but that dismisses the deliberative process, the elegance of its artistry, and the rampant creativity so apparent in the finished product. Take the entrance gate. It, too, was a cast off from a metal stamping facility. Shirley had discovered it—a four-by-six-foot stainless steel hulk—months before my project began, but something about its openwork and its heft appealed to her sense of possibilities, and so it was drafted into service to become a sliding entry gate. A fabricator added an inside facing of iron mesh, repeating the controlled rust theme of the studio and other portions of the fence.

Because this is Northern California, the garden is green year-round, which is not to say it is always the same. On early spring mornings, before the wind picks up, or late in the afternoon of a warm and windless day, the smell from a blossoming daphne (Daphne odoratum) can freeze me in place. Equal in their performance are the mid-summer dahlias that disappear in the winter but, like little green magicians, rise up to reclaim their positions as the garden queens they are. By the time Shirley was finished planting, no space or detail had been overlooked. In fact, some of the plants, such as the grasses (Anemanthele lessoniana), need a firm hand to control them, so much in love are they with the cool, foggy summers. I cut them back to the nubs in January and, within a few short months, they are green and exploding once again.

Shirley found places for my ‘Meyer’ lemon and ‘Kieffer’ lime trees that supply my friends and me with bounty year-round. There is always something to cut and bring inside. This constant supply of edible and decorative elements allows me to feel connected to the garden at all times, so the boundary between indoor and outdoor is blurred. The defined indoor space may be limited, but, depending on the time of day and the season, from my favorite chair in front of the fireplace, I can see the pond bubbling, the fig tree hanging heavy with fruit, a pair of territorial red admiral butterflies, a visiting hummingbird, the moon waxing and waning, and the occasional (unwelcome) visits of raccoons.

Many homes in San Francisco have the advantage of a hillside view. Mine does not. “Give me something wonderful to look at,” was the charge I recall giving Shirley in the same wishful spirit I told David that I wanted, “lots of glass and lots of light.” I got all of that and more than I ever imagined: the sun in the morning and the moon at night. Who could ask for anything more?

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses