Contributor

- Topics: Archive

During the short, dim winter days in the Pacific Northwest, it’s hard to get a good gardening fix. Winter unfolds in a long, bleak stretch after the new year with only brief glimpses of the sun—great if you grow moss. But when my clivia blossoms begin to emerge at the end of February they brighten my greenhouse and my spirits, helping me hang on until spring arrives in Seattle.

[pullquote]The warmth of clivia gets this gardener through the dark months.[/pullquote]

Clivia miniata first crossed my radar when White Flower Farm offered the yellow-flowered clone ‘Sir John Thouron’ in their spring 1995 catalog. The New York Times ran a story on it. Big buzz in gardening circles. At the time, only orange-flowered clivias were available to the average American gardener; the yellow bloom was rare. I’m sure I was not alone in wondering who would pay $950 for a yellow-flowered agapanthus cousin. Fast-forward 15-odd years and here I sit, a clivia fancier.

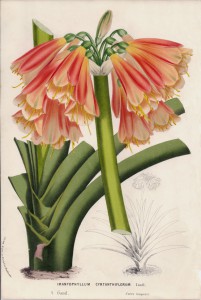

In the nearly two decades since ‘Sir John’ arrived, dedicated breeders and hobbyists have continued to tinker with C. miniata and other species. Without any headlines, a remarkable range of clivia flowers and foliage have emerged. Gardeners willing to seek them out will find clivia flowers in creamy pale yellows, rich peach and pink shades, and green-tinted bronzy red. Flower forms are varied, too, thanks to interspecific crosses of Clivia miniata with the five other species: C. caulescens, C. gardenii, C. mirabilis, C. nobilis, and C. robusta. These species have pendant umbels and narrow, tubular flowers—similar in shape to that agapanthus cousin—rather than the erect, open umbels of C. miniata. These crosses and back-crosses have borne some very charming flower forms.

In all the fuss over yellow flowers, the plant itself was secondary. Today, foliage has been improved by selective breeding for shorter, wider leaves that frame the flower without flopping over, and for forms that emphasize the attractive distichous (opposite, two-ranked) leaf arrangement. While we flower-philes weren’t looking, Chinese and Japanese breeders spent recent decades making C. miniata a showy foliage plant. They developed small plants sporting short, fat fans of almost succulent leaves with heavy, netted veining or broad variegation—or both. These little gems fit neatly on a shady windowsill instead of taking up a corner of the living room. The flower is an extra bang for the buck.

Speaking of bucks, while you may find a good inexpensive orange or yellow C. miniata at your local big box warehouse (sorry, ‘Sir James’), if you want to spend a lot there are still places to do so. Those fascinating new clivias are not inexpensive. Like everything, supply and demand dictate price. Clivias take time to grow from seed and mature to blooming size. The only way to know for sure what color the flower will be is to plant the seed and wait. Clivia growers sow their seeds and in four or five years they can ask top dollar (from a hundred to a thousand) for plants with distinctive flowers or leaves. Growers keep the most interesting specimens to enhance future generations of clivias.

Speculating with Seed

I’ve kept my clivia habit affordable and interesting by growing clivias from seed. I buy seed from growers who cross- or self-pollinate their most desirable plants. By planting seed, I assume the risk and invest the time to find out what Mother Nature has cooked up. Although I might end up with an ordinary-looking orange clivia or two, I don’t mind. I enjoy the journey as well as the destination. Fortunately, getting from point A (seed) to point B (flower) is a very simple route.

Many people are surprised to learn that clivias are extremely easy, low-maintenance plants. These are not fussy little prima donnas in spite of their exotic appearance. Clivias are native to woodland settings in South Africa (except for C. mirabilis), in areas that are cool but frost-free in winter. Outdoors, plant them in shade and enrich well-drained soil with organic matter. Clivias need to be dry in winter; gardeners in winter rainfall areas should protect plants to prevent crown rot. Indoors, give clivias bright indirect light. Use a well-drained soil such as orchid or cactus mix and make sure the container drains freely. Don’t allow water to stand in a saucer under the pot.

Whether indoors or out, a month or two under 50°F in winter encourages flowering. I keep my plants in an unheated greenhouse and run a small space heater when temperatures dip below freezing. Northern gardeners can move their potted clivia to an unheated room, basement, or garage. During this rest period, water only enough to keep the plant alive or risk crown rot. I check them once a month or so between November and February; I visit more often as blooming season approaches in late winter. Eventually, I am greeted by a fleet of bright little “suns” and I know another gardening season lies before me.

Family:

Amaryllidaceae

Species:

Clivia miniata Clivia caulescens

Clivia robusta Clivia gardenii

Clivia nobilis

Clivia mirabilis

Common names: bush lily, forest lily

Unlike most amaryllids, clivias do not form bulbs. Instead, the clivia has large, fleshy, white and yellow roots. Their seed pods (berries) can contain from one to ten or more seeds.

Foliage:

Deep green, two-ranked, opposite, strap-like

leaves. Foliage often forms an attractive, vase-

or fan-shaped silhouette.

Note: Moderately toxic to pets.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses