Contributor

We will find his spirit in the gardens he or his disciples built, exhorting us to do better, to care more, to work harder, to recklessly expend love on an intractable world, to make the world a garden.

In Memoriam to Alan Chadwick (1909-1980)

Page Smith, founding UCSC faculty member and Chadwick contemporary

Thirty-five years ago, English master gardener Alan Chadwick first wielded his Bulldog spade and fork on a rocky hillside at the University of California, Santa Cruz. From the paper‑thin topsoil of that inhospitable slope, Chadwick and his student apprentices coaxed a garden that would help launch the popularity of organic gardening, French intensive techniques, and California’s obsession with heirloom fruits and vegetables and garden-fresh cooking.

The Student Garden Project began in an era of unrest at universities across the nation. UC Santa Cruz—then the newest of the University of California campuses—was no different. UCSC’s first students were not only dealing with the political and social turmoil of the times, but the physical disruption of bulldozers reshaping the forests and meadows of the Cowell Ranch for roads, dormitories, laboratories, and classrooms.

Amidst this upheaval, students sought “a sense of place” at the fledgling university. That search led eventually to the idea for a college garden. And in one of those chance events, a Bavarian countess named Freya von Moltke was responsible for finding the gardener to create the project.

German, South African, and English Connections

Countess Freya von Moltke visited UC Santa Cruz in 1966 with her friend Oegain Rosenstock-Huessey, a mentor of UCSC founding faculty member Page Smith. The garden idea came up in conversation, and von Moltke recommended Alan Chadwick to Smith. She had met Chadwick in South Africa, where he had gone after World War II to start a theater company and to design a national display garden. But the story goes back much farther. According to Carolyn Reynolds-Ortiz (interviewed by Page Smith, in News & Notes of the UCSC Farm & Garden 67, Fall 1995),

Freya von Moltke was the wife of Helmuth von Moltke, a leader of the resistance group known as the Krisau Circle that planned the defeat of Hitler and the future of Germany after the Nazi reign of terror. Von Moltke was implicated in the Stauffenberger plot on Hitler’s life; he was tried and sentenced to death. While in prison, he wrote a series of letters to his wife Freya that were smuggled out by the prison chaplain. One of the last wishes he expressed to her was that she might start a garden somewhere as a symbol of life and vitality in the wake of so much destruction—a garden that would give young people hope and joy.

Raised in an upper-class English family, Alan Chadwick was fascinated by plants from childhood and, by his teens, had visited many of the private and public gardens in England and France. In What Makes the Crops Rejoice: An Introduction to Gardening, Robert Howard writes, “These experiences made so strong an impression on him that, while most of his peers were deciding whether to go to Cambridge or Oxford, he was planning to train in horticulture.” Chadwick served apprenticeships at some of the best-known market gardens in England and France before being captivated by the theater in his early twenties and turning to life on the stage, ultimately spending more than a decade acting in contemporary plays and productions of Shakespeare.

After serving in the British Navy in World War II, Chadwick moved to South Africa to work in the fledgling National Theater Organization but, in the early 1950s, was given the chance to garden again—first at the formal gardens of the British Navy’s Admiralty House on the Cape peninsula, and later at the vice admiral’s estate, where he created his own garden. He left South Africa in 1959, taking gardening jobs in the Bahamas and on Long Island, New York, then moving on to explore work in Australia before coming to San Francisco in 1967. There he met up with his friend Von Moltke. She drove him straight to Santa Cruz “with his sea chest full of naval uniforms, old boxes of theatrical makeup and memorabilia, and a few of the pieces of Puddleston silver and china that his mother had left him,” writes Howard.

In a 1992 interview, UCSC faculty member Page Smith recalled Chadwick’s initial reluctance to take on the gardening project at the new university:

Alan was in his fifties, a failed Shakespearean actor—failed in the sense that he’d never met with any great success on the stage and suffered a great deal from his back, which he injured during the war. He was looking for a place to live out his life in relative comfort. But Freya said to him, ‘Alan, you must make a garden here. This is your mission.’

The Beginning of the Student Garden

Chadwick chose four acres in the heart of the new campus for the garden. There, using only hand tools, he set to work on a steep, south-facing hillside covered with chaparral. Says Howard, “For the next two years, without taking a day off, this fifty-eight-year-old man worked from dawn to dusk every day of the week. Those who were there say he worked more heroically than they had ever seen anyone work before.”

Beth Benjamin, a first-year college student in 1967, remembers her fascination with the tall, lean Englishman:

Gardeners in my experience didn’t speak English and had beat‑up trucks and loud lawnmowers and lived somewhere else and came on Saturday. But here was Alan, who seemed to live in this beautiful hill-becoming-garden above the college, working doggedly with a pick and spade all day long to manifest a vision that he had blooming already in his head.

Drawn to the fledgling garden, student volunteers pitched in, hauling limestone from the old Cowell Ranch quarry to build paths and retaining walls, trucking in manure and other amendments, and loosening the rock‑hard soil with pickaxes before digging permanent garden beds. Chadwick used the “apprenticeship” style to introduce his gardening philosophy. Writes Howard,

Though he had never taught before, he threw himself into cultivating young minds and their gardening skills. His manner of teaching was the simple, classical one of combining practicality and vision. He would first demonstrate how to do something, and then put the student to work doing the same thing.

Benjamin recalls

…he’d get the tools and a wheelbarrow and trundle off down the steep path to the main garden with me trotting behind, and set me to a task, carefully and patiently showing me what I was to do before going back to his own work.

By 1969, Chadwick and his charges had transformed the brushy hillside. “From thin soil and poison oak had sprung an almost magical garden that ranged from hollyhocks and artemisias to exquisite vegetables and nectarines,” writes Howard. Chadwick had designed the site as a set of distinct “rooms” reached from a winding central path, with marbled limestone walls buttressing sloping garden beds designed to take full advantage of the sun.

Rejecting pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, Chadwick introduced the students to an organic gardening technique he called “biodynamic/French intensive,” based on double-dug beds (dug two spade blades deep) amended with compost and other organic materials. “Biodynamics” was a movement initiated by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner that, according to Chadwick, “refers to total truth—the utmost connection of spirit, mind and body, with horticulture as just one of its facets.”

“French intensive” alludes to the practice of nineteenth-century French market gardeners, who planted their carefully amended and cultivated beds using an intensive spacing, so that plants touched each other when mature. According to current Chadwick Garden manager Orin Martin, the biodynamic/French intensive method

synthesized traditional horticultural practices and observations from the Greek, Chinese, and Roman cultures on through nineteenth-century French market gardeners—folk techniques with modern scientific validity.

Chadwick’s approach worked wonders. In a 1969 article, Sunset Magazine called him

one of the most successful organic gardeners the editors have ever met. Mr. Chadwick believes that a healthy plant is not likely to be eaten or overcome by pests and his intensive kind of culture is such that the plants do stay in great health.

Sunset’s editors marveled at the transformation of marginal land into an abundant garden, reporting that

At times during the peak of the flower season, the students cut and placed ten thousand blooms a day at the help‑yourself kiosk on the main campus road. And last year the gardeners grew, picked and supplied the college cafeterias with 1.75 tons of tomatoes.

Benjamin recalls the satisfaction of the garden’s physical demands:

As an apprentice, I worked from dawn until dark and was filled with [Alan’s] dreams and our common task of bringing the garden into reality….He taught us the joy of work, the discipline to persevere in order to make a dream come true, even when we were hot and tired, and the deliciousness of resting and drinking tea after such monumental labors.

The Chadwick Garden Today

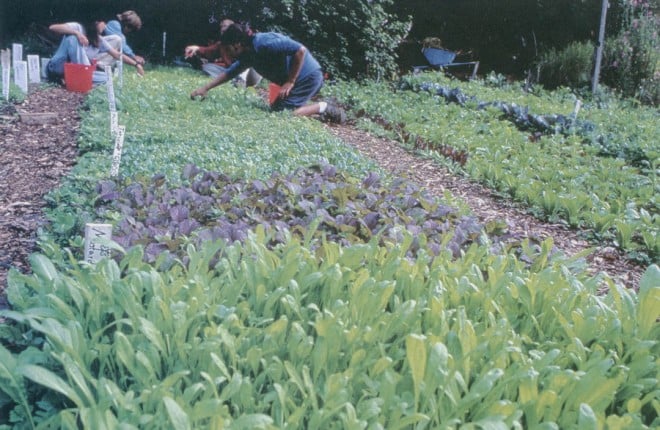

Fast-forward three and a half decades to that same campus hillside: on an Indian summer day in early September, a dozen apprentices work steadily in the afternoon heat. Instructor Suzanne Nolter uses a garden fork—its design based on Chadwick’s original Sheffield steel Bulldog tools—to unearth a crop of German fingerling potatoes. Lori McMinn, who left her marketing job at Old Navy to learn organic farming skills, seeds a freshly dug bed with salad greens. Erin O’Neill, who plans to teach children about gardening, clips fragrant leaves of lemon verbena to brew into an iced herb tea for the sweating garden crew. These are some of the figurative descendants of Chadwick’s original student apprentices.

Chadwick left Santa Cruz in 1973, due in part to disagreements with the administration over the design and management of the campus farm project, an offshoot of his original garden. He began other gardens, at the Green Gulch Zen Center in Marin County, in Saratoga and Covelo, California, and in New Market, Virginia, before returning to the Zen Center where he passed away in 1980. Although some of these gardens have since disappeared, his legacy at Santa Cruz lives on. The apprenticeship he began was formalized in 1975 as a six-month, full-time training course.

Run by the UC Santa Cruz Center for Agro-ecology and Sustainable Food Systems, the apprenticeship program brings participants of all ages from around the world to learn not only the basic skills of organic gardening and farming, but also about the complex issues surrounding sustainable agriculture and food systems. Although it now incorporates lecture-style classes, the apprenticeship continues to emphasize hands-on learning in the gardens, fields, greenhouses, and orchards of the Chadwick Garden and twenty-five-acre campus farm.

The Chadwick Garden itself has flourished under manager Orin Martin’s careful direction and the hard work of apprentices and UCSC undergraduates. Over the past twenty-five years, they’ve created a “horticultural zoo” of vegetables and flowers on the sunny, open hillside, edged by a now-mature border of native shrubs, including California flannel bush (Fremontodendron californicum), elderberry (Sambucus nigra), Matilija poppy (Romneya coulteri), and lemonade bush (Rhus integrifolia), alternating with coastal-ripening ‘White Genoa’, ‘Black Mission’, and ‘Osborn Prolific’ figs. Below the border, double-dug beds running down the slope burst with vegetables and annual flowers—from arugula to zinnias.

Based on Chadwick’s French-intensive approach, seeds and seedlings are spaced so that the mature plants form a nearly continuous canopy. In one bed, a crop of early fall mesclun mix creates a solid patchwork quilt of light to dark greens, with white-washed bed signs demarcating the kinds of plants within—Hon Tsai Tai, ‘Red Russian’ kale, Tokyo Bekana, arugula ‘Astro’, ‘Yukina’ savoy. In another, a late planting of pole beans climbs a trellis, flanked by maturing red and green butter lettuce that fill the remaining bed area. Crops of leeks ripen beneath young fruit trees next to beds of closely planted sweet peppers, their fruit growing dark red with the fall heat. The fertile, carefully managed soil, richly amended with compost made on site, can support this tight spacing, generating abundant harvests from a relatively limited space.

Perennials anchor each bed, offering shelter and food for beneficial insects and birds. On a hot fall day, bees visit the salvia plantings—among them Salvia greggii ‘Chiffon’, S. chiapensis, S. ‘Purple Majesty’, S. ‘UCB Pink’, and S. ‘Indigo Spires’. English and French lavender (Lavandula angustifolia and L. dentata), penstemon, lion’s tail (Leonotis leonuris), Mexican sunflowers (Tithonia), woolly lamb’s ears (Stachys byzantina), fountain grasses (Pennisetum), tree dahlias, and Fuchsia thymifolia add their own colors, textures, and scents to the blend.

This emphasis on variety and diversity is no accident. The boom in “specialty crops” of salad greens, potatoes, apples, and other produce and flowers can be traced in part to Chadwick’s insistence that his students look beyond the narrow offerings of grocery stores and mainstream nurseries to explore the breadth of heirloom and classic food and ornamental crops. Paul Lee, a former philosophy professor at UCSC who helped bring Chadwick to Santa Cruz, recalled in a 2001 interview,

[Chadwick] would inveigh about how they could reduce the entire apple crop in America to one variety—‘Delicious’—just because of its shelf life, and it tasted like crap, when there were 300 varieties of apples. He was really the first guy to extol heirloom species, diversification—you know, twenty kinds of salad greens. He was aware of all that way before it caught on anywhere else.

Like Chadwick, Martin stresses the importance of varietal selections. Each season he and his students trial vegetable and flower varieties, honing their knowledge of what grows and tastes best under Central Coast conditions. By Thanksgiving they’ll have planted out fifty to seventy-five varieties of garlic, including ‘Purple Glazer’, ‘Uzbek Turban’, ‘Chet’s Italian’, ‘Susanville’, and ‘Chinese Pink’. Spring pepper crops can include several dozen varieties of sweet, mild, and hot peppers. A wide selection of Asian greens—what Martin calls the “unsung and under-appreciated”—broadens the palates of students and shoppers at the weekly market cart.

Perhaps recalling Chadwick’s sentiments, staff and students have packed a portion of the garden site with 130 varieties of apple trees. They include familiar names (‘Granny Smith’, ‘Yellow Newtown Pippin’, ‘Golden Delicious’) along with classic heirlooms (‘Cox’s Orange Pippin’—Chadwick’s favorite and a notoriously difficult variety to cultivate—‘Hoople’s Antique Gold’, ‘Spitzenburg’, ‘Egremont Russet’, ‘Calville Blanc D’Hiver’) and new introductions (‘Sunrise’, ‘Sweet 16’, ‘Pristine’, ‘Pink Lady’). All are on dwarf and semi-dwarf rootstock. Most trees top out at eight feet or less and can be harvested without using a ladder. Each year Martin introduces the community to the wealth of varieties they can grow at home through a series of standing-room-only public lectures on fruit tree care and varietal selection.

Flanked by the vegetable beds and the apple and pear orchards, a terraced section of the Chadwick Garden supports a collection of subtropical plants. Although heat-loving fruit trees do not always produce optimally in Santa Cruz’s temperate climate, this sheltered area has an especially warm microclimate. The slope absorbs and reflects the sun’s heat, supporting oranges, lemons, grapefruit, cherimoyas, and avocados. Most of the older citrus are grown on semi-dwarf rootstock. Newer selections are grafted onto dwarf rootstock to make them easier to care for.

The Chadwick Garden continues to evolve as perennials mature, the gardeners experiment with new varieties, and new crops of students add their own touches. And although much has changed on campus since Chadwick first arrived at UCSC, the garden retains many of the elements and the culture he introduced. The old-fashioned roses he loved—‘Madame Alfred Carriere’, ‘Lady Foreviot’, ‘Etoile de Hollande’, ‘Sombreuil’—still climb the trellises and blossom along porch railings. Staff and apprentices still sit down to tea after a long day of work. And students still seek a sense of place in the garden’s tangible routines of digging, planting, and harvesting. Chadwick liked to say that the gardener doesn’t make the garden—the garden makes the gardener. For thirty-five years Chadwick’s garden has been making gardeners steeped in his philosophy that we should “Listen, and let the garden be your teacher.”

Apprenticeship in Ecological Horticulture at the Alan Chadwick Garden

To date, more than a thousand students have completed the apprenticeship program. The course covers an array of basic topics, including soil management, compost-making, propagation, irrigation, crop culture, and pest and disease control, as well as classes on such topics as sustainable food systems, marketing, small farm planning, and beekeeping.

Many apprenticeship graduates go on to start their own organic farms or market gardens, often taking on apprentices as part of their operations. Others work for school, community, and urban gardens and training programs, passing on the skills they’ve learned. A number have started organic landscaping businesses. Many of the international participants have founded apprenticeship-style training programs in their home countries, while other graduates travel abroad to work in the Peace Corps and other rural development projects. And some graduates have helped build the burgeoning organic food and farming movement as policy makers, extension agents, and staff of organic certification groups.

For more information on the six-month training course, visit www.ucsc.edu/casfs, send an email to apprenticeship@ucsc.edu, or call 831.459‑2321.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Responses