Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Much of my discovery of new natural dye plants and colors results from a willingness to be open. The alchemy of the dye-making process relies on elemental factors: soil quality, ripeness, season, rainwater, Oakland tap water, and my own patience and participation. The joy of making natural dyes—as much as and sometimes more than the results—is often the sweetness that keeps me wanting to discover more. I love the imbued poetry of nature’s color timing rather than my own. In my art making, I am fascinated with the idea of, and variation in, living color palettes and how I can curate and frame natural color in a contemporary light.

It is tragic but true that because we are out of sync with our natural environment we are on the brink of losing both cultural memory and biodiversity. Ecoliteracy, a term coined by environmentalist Fritjof Capra, promotes ecology-based education for sustainable living. The reasoning is that if we learn to understand our environment on a deep emotional level rather than just through abstract fact-based knowledge, we will be motivated to care for it. Learning plant identification, the pleasures of growing one’s own food, or how to create a natural color palette—a practice once common before the introduction of artificial dyes and a mechanized textiles industry—all enhance our ecoliteracy.

A broader conversation occurring in the mainstream textile industry surrounds color permanence and stability. Yet, issues of scalability and the lasting value of “permanence” frustrate artists who work with natural colors and are aware of how complex and varied they can be. Although many plant dyes can be lightfast for hundreds of years, others are not. But is that reason enough to not use many plants that provide interesting and unique colors?

Gathering—both people and plants—to dye textiles and clothing can become a seasonal ritual with harvests timed for the peak of ripeness or in connection to the unique offerings of a particular environment. Experimenting with fallen redwood cones is awe-inspiring, both from the color that emerges—deep mauve, purples, and blacks—and the smell of the dye bath—like a walk in through a coastal redwood forest in the rain. I discover a deep sense of place and a connection to the world around me in a way that squeezing a tube of color cannot provide. Making natural dyes unleashes the potential for designing as nature does, with purpose and beauty.

I believe the future of color creation needs to diversify, including how color is used on both the personal and industrial level as well as expectations about its lifespan. In my own practice working with a plant-based palette, I grow or forage materials in my Oakland/Berkeley neighborhood. Often I use whole plants rather than extracts. This means I need to be aware of their seasonal availability, growth cycles, and color potential. With this contextual knowledge I can develop a color palette specific to a place and/or a time of year—much like planning a seasonal menu.

Working from this whole systems approach and with a love of “stacking functions” (getting multiple uses from one action or material) I realized my work fit very nicely into a permaculture framework—a system that has been described as “revolution disguised as organic gardening.” In 2007, I founded Permacouture Institute—it seemed like the perfect play on words—to sync ecoliteracy to healthy design and promote curiosity about the world around us.

Permacouture Institute is an educational non-profit that shares ecological relationships and expands ideas of nature and nurture through the revival of plant- and place-based color recipes. Through experimentation with weeds, food waste, and the biodiversity of local and seasonal plant-based dyes, Permacouture works to inspire an appreciation and awe for the natural world. www.permacouture.org

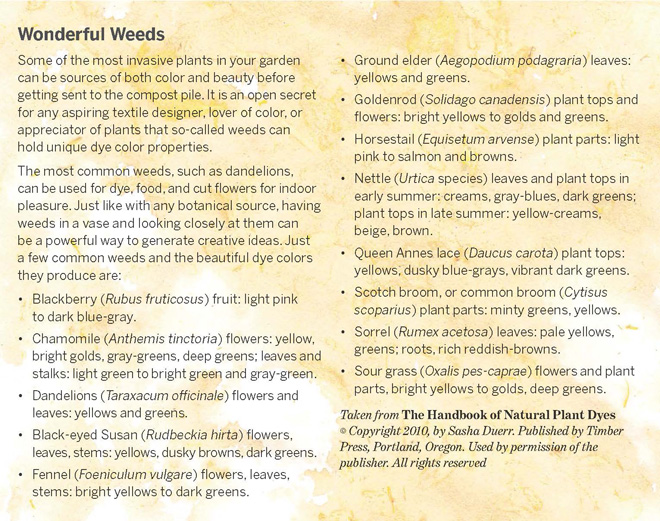

The Handbook of Natural Plant Dyes

Personalize your craft with organic colors from acorns, blackberries, coffee, and other everyday ingredients, Sasha Duerr, Timber Press, 2010

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses