What a Bee Knows and Why it Matters with Garden Futurist Stephen Buchmann

Contributor

- Topics: Garden Futurist

Spring 2023

Listen to the Podcast here.

Pollination ecologist Dr. Stephen Buchmann has been studying bee biology for more than four decades.

His new book is What a Bee Knows Exploring the Thoughts, Memories, and Personalities of Bees.

“In every possible way, my life has been a wonderful and fascinating journey into the private lives of bees while discovering some of their innermost mysteries.”

This episode is cohosted by special guest Aaron Anderson whose recent article for Pacific Horticulture “I Did My Graduate Research in a Garden Ecology Lab, This is What Gardeners Want to Know” is now available.

Sponsored by Bartlett Tree Experts

Sarah Beck: You’re listening to Garden Futurist. I’m Sarah Beck, here with Aaron Anderson.

Aaron, some folks in our audience might hear your name and think, “Why do I know that name,” and realize they just read your article, “I Did My Graduate Research in a Garden Ecology Lab, This is What Gardeners Want to Know.”

Aaron Anderson: Yes.

Sarah Beck: I spoke with Steve Buchmann, a pollination ecologist who has been studying bee biology for more than four decades. I talked to him about his book, What a Bee Knows: Exploring the Thoughts, Memories, and Personalities of Bees.

Steve does this amazing job sharing frontiers of research. As a garden futurist, I get super excited about that stuff where it’s like, we don’t really know where research is going to take us in the coming years. He mentions all these cutting-edge things, from the microbiome to looking at bloom times, and obviously football, American soccer, there’s a lot of things bees are doing that we may understand a lot better in the coming decades. But I’m wondering, because you do have so much expertise in this field where you see just where you see the most important threads in this conversation that I had with Steve, because I do think that the gardener piece is so important, and I’m wondering, where should we have our eye on the ballon something really specific as we’re listening to this conversation?

Aaron Anderson: I think that what is really neat about this book, What a Bee Knows, is that he covers this amazing breadth of different topics and research. The first part’s kind of a great primer on bee biology and ecology, but then it gets into all of this really interesting bee learning, bee cognition research.

I think that the things that were striking me the most as I was reading this and kind of thinking about it, is just the complexity of everything that there is to know about bees, both their behavior in your garden as well as things that are happening at the neural level. There’s a lot of things we as people, and even historically, researchers have kind of assumed was simpler than it actually is.

I think one of those examples was thinking of the flower-bee relationship as this mutualism, but in fact, right, it’s not both these parties benefiting. It’s so much more complicated because it is an herbivore-plant interaction. So it’s also this arms race. There’s both flowers and bees that cheat the system.

So this might not necessarily be, you know, super applicable to the home gardener who just wants to provide habitat. But it’s an example of, I think, all of these things with pollinators being really complex.

Sarah Beck: I did a little bit of gushing when I emailed you, but this book is really incredible. I have to say, I think even for those of us who are like, “I think I know something about bees and pollinators,” this absolutely blew my mind.

Steve Buchmann: You know, I’m a pollination ecologist and I normally spend my time chasing bees around the desert and also the tropics, figuring out what they do in terms of what colors they can see, what they smell, quantifying the amount of pollen and nectar that they take from flowers.

So I had to really spend a year or so researching and contacting my neurobiologist friends and reading literature that I normally don’t read. So everything from behavioral stuff to physiology, probing the bee brain. Was really a lot of fun.

Sarah Beck: I have to ask you about the bee microbiome. There is so much interesting science happening right now on this topic relating to human health. I guess it shouldn’t be a surprise that bees need microorganisms to be healthy. Can you tell us a little bit more about this, and also how the heck did we learn this?

Steve Buchmann: Actually, when I was a research entomologist working for USDA Federal Lab in Tucson quite a few years ago, I started out working with a microbiologist. We were the first team that found some of these helpful bacteria in honey bees and also some solitary bees as well.

But now things have kind of come full circle, and I’m collaborating with colleagues like Brian Danforth at Cornell, other colleagues at my alma mater, UC Davis, also UC Riverside. And now with the ability to go to these bees and basically extract some liquid basically from the adult bee gut or, my favorite, to go into the brood cells and pull out some of this bee bread, pollen-nectar mixture.

And we do a DNA extraction. I mean, it’s just like forensics, right? To identify a serial killer or something. We extract the DNA, we use PCR to ramp it up, and then we do either shotgun metagenomics, or—

Sarah Beck: What does that mean, shotgun metagenomics?

Steve Buchmann: That one is kind of new, but basically in the old days you would just amplify one type of DNA and identify it alone.

But with this new technique on rapid, like Illumina sequencers and that sort of thing, you might have literally dozens or hundreds of bacteria or fungi species in one sample. So basically, you break everything up, you amplify it, and then you have certain matches, basically. And you look in these global DNA libraries and you can identify the species.

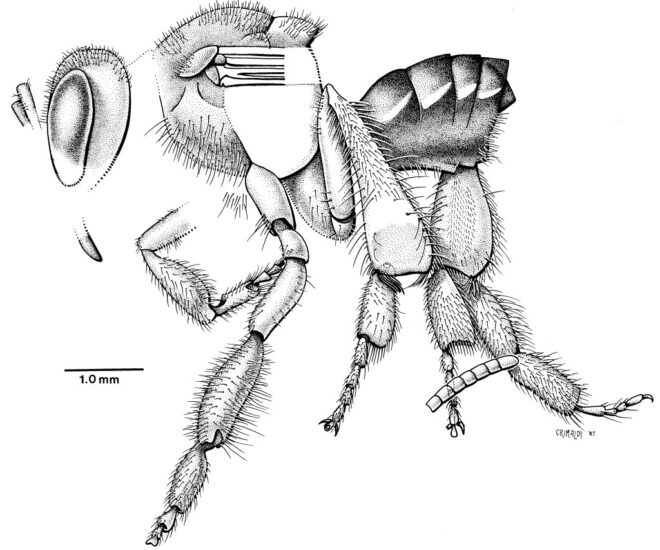

Now you can’t always identify them, because there are a huge, huge number of new species out there. But I would say in the last decade that we’ve made huge progress in trying to identify these. One of my favorites is an Arizona bee called Ptiloglossa. It’s a buzz pollinator, so its females go to deadly nightshade flowers and vibrate their bodies, turning them into like a little tuning fork and they blast the pollen out.

This is like my favorite research thing that I’ve done my entire career.

Sarah Beck: That’s so cool.

Steve Buchmann: But when you open up their cells, you go, “Whoa, is there a brewery nearby?” So you look at these cells and they’re filled with mostly nectar, with kind of a trace of pollen, and they’re bubbling CO2, and it smells like beer.

So when we analyze these, we find out that, hey, there is actually—well, the taxonomy’s changed a little bit, but let’s just say Lactobacillus to be kind of casual about it. But these are the same sort of bacteria that are in your morning yogurt.

What we think is happening now is that certain bees, not all of them, but certain bees are getting a big hit of nutrients by eating the sort of microbial meat, if you will, rather than the pollen. So we think of these bees as sort of being microbial farmers, like us taking probiotics or something.

The bees, even though they don’t live a long time, they can be hurt or killed by bad guys, different fungi or even the wrong bacteria. So it seems that some of these Lactobacillus and other bacteria are in there and then they’re outcompeting the bad guys. So basically, you’ve got kind of a good versus evil thing happening within the gut of the bee or in their brood cell.

Sarah Beck: Let me just jump back to the fact that this book is called What A Bee Knows. And you say that bees have an extraordinary ability to think, solve problems, learn, remember, and that learning is involved in virtually every aspect of bees’ daily lives, and bees use tools.

I never would’ve looked at this YouTube video, but you mentioned in the book, the bumble bees playing soccer video. And of course I immediately had to look at this and it’s really worth seeing. This is from Queen Mary University of London, the laboratory of Lars Chittka. Can you explain why the researchers did this, other than the obvious love the English have for football?

Steve Buchmann: Lars Chittka is a good friend and colleague. I’ve published with him now and then. But he and his lab, his students, they really wanted to investigate the behavior of what we have to really call tool using.

I mean, the fact that any animal besides us people used tools was kind of broken wide open, I guess, maybe in the ‘60s by Jane Goodall when she saw her chimps putting little grass blades into termite nests and then pulling the termites out and eating them. And they would even cut the grass to the right length. So they were making and using a tool, and this blew everybody away.

It turns out that bees are doing similar things. So my favorite from the Chittka lab was not just training them to push little round balls into an area to get a reward, but my favorite is tool using that they demonstrated by pulling strings. This is an amazing video to watch, also available on YouTube.

So they trained bees to pull a string and you really need to look at the video to understand what’s going on. But there’s a plastic cover over a round blue disk that has a little well in it. And they filled that with sugar water, which the bumble bees wanted to get because they love sugar water, little sugar junkies. They basically had pre-trained bees and then untrained bees that watched their hive mates do this. And then they could do it simply by watching. So then you have an untrained bee that works really, really hard to pull and pull and pull this little string and this heavy blue plastic circle until it gets out from under this lid. And then they hop on and drink up the soda water, basically.

It’s neat to watch them push the little balls or pull the string. His students have done something recently, I don’t know if it’s on YouTube yet, but they put some little wooden balls just in an arena where the bumble bee workers had access to and no reward or anything.

And I don’t know if I’m quite willing to believe this yet, but they’re hypothesizing that the bees are basically playing by moving these little balls around.

Sarah Beck: Wow.

Visit the 2023 Design Futurist Award page.

The Design Futurist Award elevates inspired gardens and designs that showcase our reciprocal relationship with nature. These awards demonstrate personal engagement and appreciation of the beauty of resilience, stewardship of biodiversity, respect for our local ecologies, and the environment.

Steve Buchmann: So not quite sure if I’m ready to go there yet. But certainly their demonstration of tool using is pretty remarkable.

Sarah Beck: So one of the most mind-blowing moments of your book for me was the section where you talk about bees engineering bloom times. This was a phenology concept. Can you share a little bit of that story with us?

Steve Buchmann: Yeah. Some researchers in England and I don’t know that it’s been repeated and it is, it is a bit controversial. So we only have this one paper, one example.

European bumble bees, I think it was Bombus terrestris, which is pretty commonly used there to pollinate tomatoes in glass houses. They observed that some bees would go and cut little notches, little holes in the leaves of tomato plants. And they thought, “Wow, why are they doing this? There’s no food there. What is going on?”

So the long and short of it is that they are saying that, just like a human gardener might pinch buds or remove old flowers to promote more budding or flowering, that hey, maybe the bees are doing the same thing. So that they are anticipating that their actions will cause future flowering, maybe, in a few days’ or weeks’ time.

So to me, that one is really, really crazy if it’s true.

Sarah Beck: It’s pretty out there.

Steve Buchmann: Yeah, so the bees might actually be engineering bloom time.

Sarah Beck: One of my favorite quotes from your book is, “Bees might as well be alien life forms from a distant planet in terms of what we might envision of what they’re thinking.”

Steve Buchmann: I’m not sure that I’m willing to go quite as far as Lars Chittka goes in his recent excellent book, The Mind of a Bee, but I’m probably 90 percent of the way there. I would agree with Lars that I think bees and a lot of other insects probably have a primitive form of consciousness, and we really don’t know what that’s like.

I believe that bees are sentient , in terms of the definition of sentient being able to feel pain. Some people would say that the sentient goes to other emotions as well, but I’m, yeah, not really, not really sure about that.

I talk about in my book some researchers that think about, well, certainly we know that bees sleep, and they have sleep and wake cycles, they have different sleeping postures from some chemical studies. We think that there’s memory consolidation happening during sleep, just like happens in us and other animals. So from that standpoint, it might not be too much of a stretch to “Well, if they’re doing that, if it’s something maybe like REM sleep or whatever, you know, Maybe bees are dreaming.”

Sarah Beck: They might be thinking about the football game.

Steve Buchmann: Yeah, they might be thinking about playing football, or they might be thinking about, “Wow, I found this great flower patch yesterday. I’m going to go back.”

Sarah Beck: You explain that bees can be solitary, social, or parasitic, and almost 80 percent of the world’s 20,000 described bee species lead solitary lives. The social bees seem to get a lot of press. I think we hear about them a lot, but what are those solitary bees doing?

Especially as gardeners, we feel really lucky when we see a native solitary bee here in the West. And I’m not sure that as gardeners, we really know what they’re up to when we see them.

Steve Buchmann: Yeah. You’re entirely right. The social bees, like honey bees and to a lesser extent bumble bees, tend to get all the press, especially honey bees.

But we do have around 3,500 native solitary bees in the United States, and the vast majority of them are ground nesting. And there are other solitary bees which can nest in broken off twigs, like elderberry twigs or from a rosebush, that sort of thing. So they’re cavity nesters.

Probably in the West as gardeners are probably more likely to see furry, chubby little bees that are in the genus Anthophora that fly quite fast and hover. Some of them have nicely striped black and white abdomens. Others can be mostly gray. Other solitary bees that gardeners might see would include the leafcutter bees.

Some gardeners might have some unkind words for the leafcutter bees because for roses and a few other plants, you can see these little semicircle notches cut out of the margins of leaves. And those are due to female leafcutter bees in the genus Megachile collecting those leaves and bringing them back to their nest, basically wrapping up their larvae and their nectar and pollen food in them.

I like to think of these as almost like baby blankets for the bees. So the female bees are usurping some chemical defenses from the plant against bacteria and fungi. And they might make this nice little wrapper to hold the baby bees, basically.

Sarah Beck: If they want it, let them have it, right?

Steve Buchmann: Right I like to tell people that, yeah, don’t get out the can of spray because those few little bits of leaves are not going to kill your rosebush or whatever plant the leafcutter bees are taking a few bits from.

Sarah Beck: Oh, and you mentioned the cavity-dwelling bees. Are there some particular plant materials we should be leaving for them?

Steve Buchmann: Yeah, dead canes of things, like if you’re lucky enough to live in kind of a wild area with elderberry. They also get into fennel, or like I said, rosebushes or similar things that are kind of pithy twigs that when you snip them off, it leaves a nice little cut area that they can get into.

Sarah Beck: I want to get right to the bees and plants conversation because we’re gardeners and we love the connection to plants and not just pollination, because you actually make a distinction between the word visitors and pollinators. I’m curious what the difference is.

Steve Buchmann: Yeah. Unless you really study these plants, probably from a natural history or a scientific viewpoint, you wouldn’t notice. So not every floral visitor is a pollinator.

One of my best examples is to think of it in terms of thieves or robbers. So there are bees that are nectar robbers. For example, some of my favorites, the gentle giants, the big black carpenter bees have these stiletto-like mouth parts. And they will go to the base of flowers that are too long, like tubular trumpet-shaped flowers, Gelsemium or—here in Arizona, I don’t know if you have it in California or other areas of the West, but—Tecoma is one. Bignoniaceae.

A lot of these things are too long for them to get their short mouth parts into. So the bees learn to go to the base of the flower, and with those blade-like mouth parts, just cut a slit. And then, pretty soon, they’re not going in the front door. So they do not contact the sexual parts. They don’t pick up pollen and deposit it on stigmas, but they are really great at robbing or stealing that nectar.

Sarah Beck: That’s sneaky.

Steve Buchmann: So that’s a good example where everything is not perfect in the mutualism land of pollinators and plants.

Sarah Beck: You just mentioned mutualisms, and I think of the simplest version of this idea is the bee gets a floral reward like nectar or pollen, and the plant gets the pollen transportation service, the pollination. Is mutualism more than this? Would you mind sharing some of the purposeful pollination story? I know you mentioned this in the book.

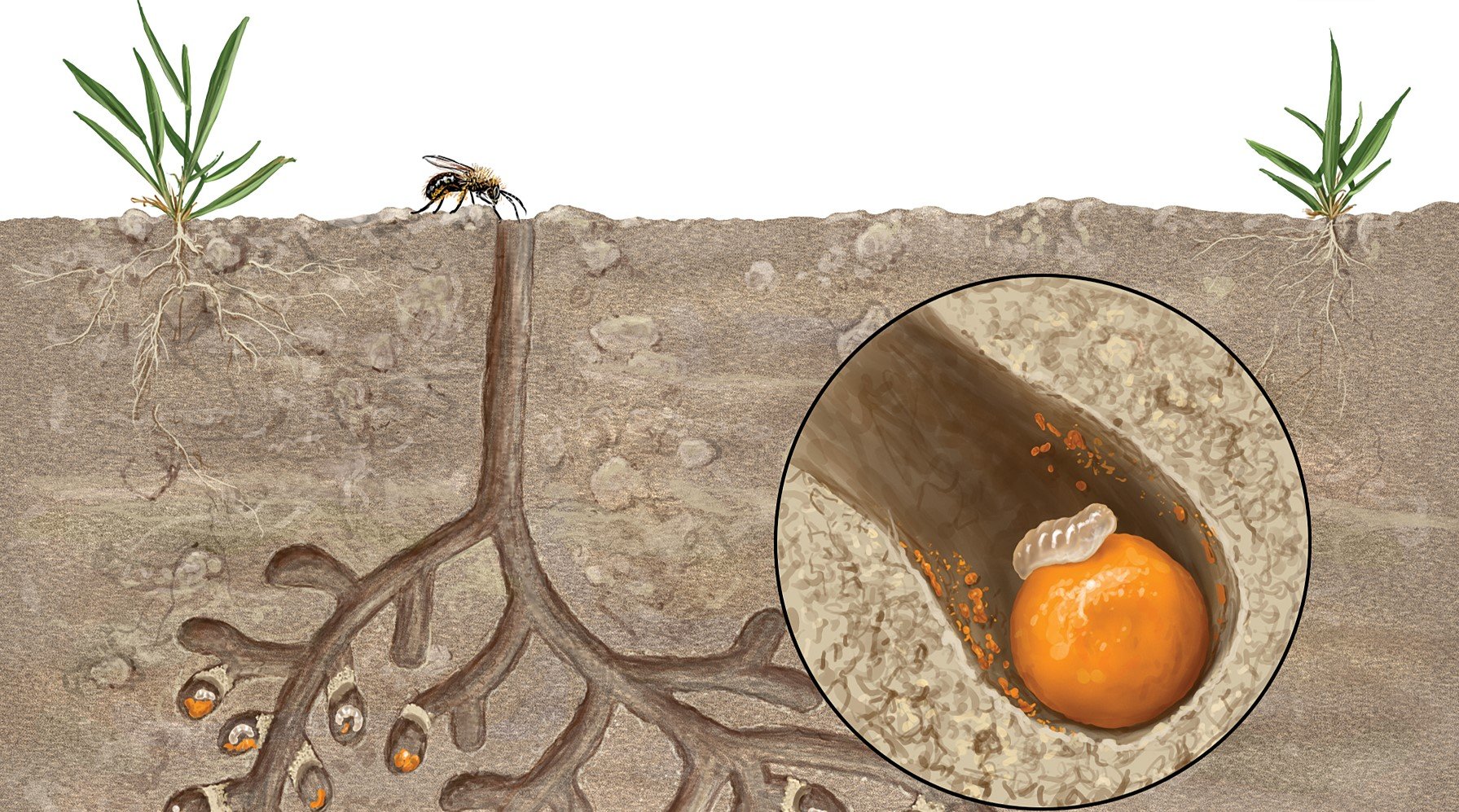

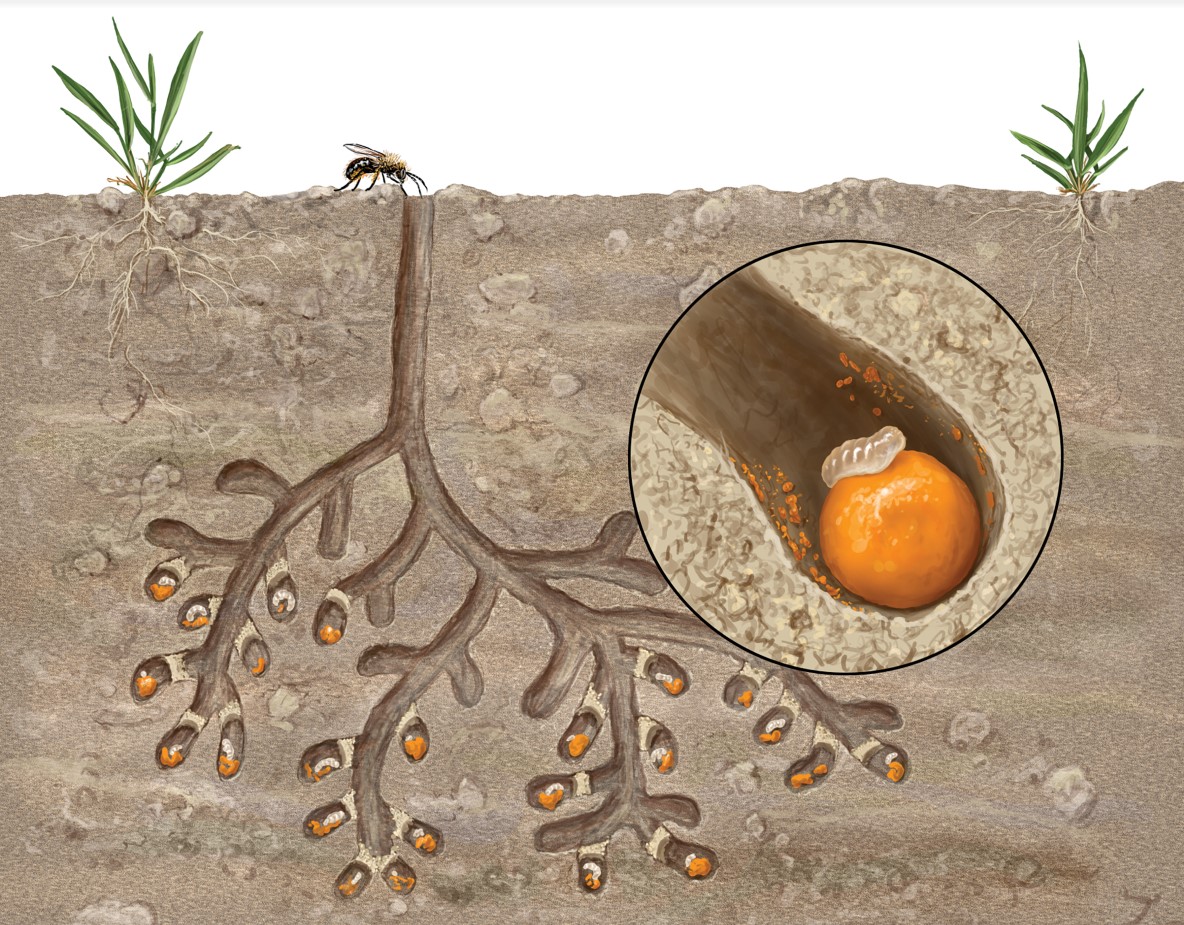

Steve Buchmann: Yeah. In my book, I talk about these things as sometimes being more like an arms race. So the bees are really greedy and those female bees want to get every last drop of nectar and every last speck of the pollen. It’s food, it’s high-energy food, flight fuel for the adults. It’s pollen mixed with nectar, we call it bee bread for honey bees, but for solitary bees, it’s the same thing. They make a little ball of pollen and nectar, lay an egg on it, and that’s the complete food that that insect needs to go from egg to adult. Everything is there, provided by the mother bee.

So the bees would like to get every last scrap and obviously it’s very energetically expensive, right? For the plants to make all this stuff. All the nectar and pollen. Pollen is basically like plant sperm, gametes or sex cells, for the plant. And not every bit of that can disappear down the gullet of a bee and have the plants survive and reproduce into other generations. So it tends to be that the plants try to hide a bit of the pollen. I mean, sometimes you can have a perfectly good plant reproductive system where only one one-thousandth of one percent of the pollen gets transferred from a plant to a stigma.

So all you need are just a minute number of pollen grains to find the right spot, and aided to get there by the “helpful” bees. That’s helpful in quotes, because they’re trying to feed themselves. They’re not trying to do a good deed for a plant. You know, they don’t get up every morning and say, “Oh, on my to-do list, it says, ‘Pollinate 10,000 flowers.’”

Sarah Beck: We’re anthropomorphizing here, but I think it is interestingly helpful to do that because it gives you this sense of what these interactions really mean for the individuals and their needs.

Steve Buchmann: Most of the world’s orchids produce no accessible pollen or nectar for pollinators. So they are basically shamming. They’re fakers. They’re cheaters in the system. They look like they’ve got a bunch of goodies. They look good, they smell good. But when the bee arrives or wasp or fly, whatever happens to be pollinating the orchid, they’ll get some shrink wrap pollen glued to their head or abdomen and, generally, no tasty nectar.

That is something we need to consider in this sort of arms race. One interesting thing that makes the system work is that there are what I call safe sites on bee bodies.

It’s just like you’ve got an itch on your back and you can’t reach to scratch it, so, when the female bees go to groom this pollen off when they’re back at their nest to shape it into that pollen ball for the larvae, they can’t get it all off. So when they go fly out to the next flower, the stigmas are often in the right position to scrape some of that safe site pollen off.

So here is part of the arms race, right? The plants are playing this essential game, so they’re hiding their pollen on certain parts of the bees where the bees can’t reach it.

Sarah Beck: That reminds me of like, the spot you’re supposed to put medicine when the vet gives you something to the dog, and you have to put it on their back where they’re not going to lick it.

I’m really curious to hear more about the extreme specialists.

Steve Buchmann: Here in the Southwest, especially in the deserts, one of my favorite bee genera is called Diadasia.

And the genus is pretty big, but it really has three kinds of specialists and one kind goes to globe mallows or other Malvaceae, one kind visits sunflowers. This one’s pretty common in California on sunflowers, it’s called Diadasia enavata, it’s a pretty big fuzzy bee. And then my favorites here in the desert around Tucson is Diadasia rinconis. And it’s a super specialist. It only goes to prickly pear (Opuntia) and cholla (Cylindropuntia) cacti and nothing else.

So these bees are specialized, and by specializing they become more efficient at finding and collecting pollen and nectar from these plants. But they also put themselves in a little bit of a bind, because if that plant doesn’t bloom because of inadequate rainfall or whatever, and they come out and their host plant isn’t there, they all die.

They do have a little bit of what I like to call a bet-hedging strategy. So some of these solitary bees can act almost like underground seeds in a seed bank. So some of these bees have been noted to wait up to five or even seven years. to emerge from the ground until the conditions are just right.

Read Aaron Anderson’s new article: I Did My Graduate Research in a Garden Ecology Lab, This is What Gardeners Want to Know

Sarah Beck: Wow. How do they know?

Steve Buchmann: How do they know? I know. We really don’t know how they know. Is it just temperature? Is it soil moisture? I’ve even had this wacky idea that plant roots and mycorrhizae may actually be in some kind of communication with bees so that their pollinators are in tune with when they bloom.

That’s total wild speculation. But who knows?

I like to think of these solitary bees as seeds sitting there waiting for the right condition, and then their plants bloom, they come out. The females often don’t live very long, typically just a few weeks, maybe a month. When they first come out, they, they mate, they make a nest, they provision for it, but then they die off. So typically for a lot of these bees, you have 10 or 12 months out of the year when it’s just the underground larvae or pupae resting in a cell below ground. So you don’t see the adults at all.

So one of the major frustrations of being a pollination ecologist is that you only get one two- or three-week shot at studying these systems every year. And so a lot of times I think, “Wow, I’m in my fifth or sixth year of this study. Why?” You know, because I only have a couple weeks each year to try to sort it out.

Sarah Beck: I do want to ask about the social bees, because bumble bees are very charismatic, and you’d mentioned the black carpenter bees. I’m curious about this lifespan difference with the short lifespan. What’s the story with the longer lifespan for the social bees? Why is their lifespan so long?

Steve Buchmann: Typically, because in the case of a honey bee queen or even a bumble bee queen, you have an individual that lives for, well, months, almost a year in the case of the bumble bees, and actually several years, typically two or three years in the case of a honey bee queen.

So you can think of this perennial organism, like this flying social amoeba that needs to go out and send its foragers, these little pseudopodia, if you will, into every nook and cranny to find pollen and nectar resources and bring them back.

So it’s really a high-energy system, especially for honey bee colonies, and that is often one of my worries for putting big concentrations of honey bee colonies, big apiaries on forest service public lands, or certainly in a state park or something, because they’re pulling a huge, huge amount of pollen and nectar out of the system that, had it remained there, it would be available not just for native bees, but also hummingbirds, nectar bats, butterflies, flies, wasps, all the pollinators.

There are some solitary bees that have very long lifespans, like I mentioned the carpenter bees. So not all solitary bees have super short lifespans and are specialists. For example, carpenter bees live for a long time and they go to a lot of different plants, so they are not specialists.

Sarah Beck: As a gardener, a lot of us really like the idea of supporting the specialists, but also having some of those the plants that attract a lot of generalists because that’s when you get a really big party going on in your garden. Those are those fun moments, right?

Steve Buchmann: Yeah, and I would I guess throw out here before I forget saying it, that some of the best things you can plant to attract a lot of diverse bees would be things in the sunflower family (Asteraceae). So they have an open platform and a lot of bees and other insects can come to the pollen and nectar party.

Also, believe it or not, one of the genera of wildflowers, annual wildflowers, that attracts more different kinds of bees than almost any other is Phacelia. So that’s a really nice one to plant.

Sarah Beck: We’re not just talking about a domestic sunflower. There are a lot of interesting native sunflowers.

Steve Buchmann: Yeah. I would advocate people to use native plants or heirloom varieties Too often we go to a nursery and we buy the latest, greatest, roughly quadruple-petaled oddity, really a hybrid.

Actually, I would like to say one last thing in the category of advice to gardeners.

Sarah Beck: Please.

Steve Buchmann: So one thing I’d really like to say and to reach out to home gardeners, probably the best thing that we can do to promote pollinator health and conservation is to plant a diversity of flowers. Especially native flowers that are adapted to your local climate, soils, rainfall patterns, all that.

If you can’t do that, at least do some heirloom varieties, because those are really good. If we have planted flowers that bloom in the spring, summer, and fall, then even some of these specialists, there could be a whole turnover of different specialists or like I mentioned, bumble bees or carpenter bees or honey bees, which need food throughout the year.

Then you have a smorgasbord of flowers for them present during the whole year. And that’s really important. It’s obviously important not to use insecticides or to use them sparingly or perhaps, if you can’t avoid it, maybe spray something that is a little more bee friendly and hey, it’s easy to go out there and spray at night when the bees are not active.

So that’s one thing that could be done. And then with herbicides, I’ve been starting to tell people not to use herbicides in their garden. And I’ve gotten some shocked looks from scientists on this too, because if you go to the literature, you basically find that almost all the common herbicides that have been tested in labs against bees indicate that herbicides do not kill adult bees.

That’s pretty much true. But what our microbiome group has just found out and is just about to publish is the fact that herbicides negatively impact those good guy microbes in the cells for the developing bees. So herbicides are knocking out helpful microbes, bacteria and yeasts and that sort of thing in bee cells that can be killing young developing bees, but we’d never know it because that’s never the test that’s done in the lab. They always expose adult bees and the bees are alive and they go, okay, herbicides are safe for bees. But we’re saying, “Now, no, wait a minute”

I’m not saying all herbicides, but of certain ones that we’ve tested so far, which were some of the most common ones, they had really negative impacts on larval bees and their nests.

Sarah Beck: That’s very significant, and I think even for people who are doing what we call the #LifeNotLawn conversion, where they’re pulling up turf and wanting to in a native or you know, a garden with a lot of habitat, you do run this risk if you’re planning to use herbicides of doing some damage to get rid of that turf.

These are very good cautionary statements about this.

From a gardening perspective, I think it gets easy, for me anyway, to start getting overwhelmed, because I start thinking, there are these certain things that I want to do and it’s like, “Oh, I need to make sure I’m leaving some leaf litter.

Oh, the tips of some stems seem like they might be right for a bee to go in, and it’s like, how do we not get frozen when we’re in the garden trying to make maintenance decisions and care decisions in the garden.

Maybe some of this is about observation. Do you think it is sort of like getting comfortable with your own observations?

Aaron Anderson: I think that you make a really great point, and I think something I should note is that even though there are these complexities and there’s so much going on and all of these things that could be impacting bees in your area, in your yard, in your landscape, I think that the message would be, yeah, you’re right. Not to get bogged down with all those details and worrying about them. Instead realize because there are all of these different complex pollinator conservation issues potentially going on, anything you do is going to be beneficial.

Just focus on some of those main messages: providing a diverse suite of native plants, try to have it flowering all season long. Like you were saying, I think it’s great to have observation in your yard and see how the things that you’re doing are kind of changing not just pollinators, but all sorts of insect life in your yard.

If you are planting certain flowers and you’re seeing lots of bumble bees go visit those flowers, that’s great. Make a note of that and then maybe plant more of those next year, plant them in a different part of your yard if you have a big yard. So I think there’s a huge place for observation as you’re both gardening and also just trying to provide habitat for invertebrates and pollinators in particular.

Sarah Beck: I’ve had my own attempts at doing bee identification. I have a fabulous book and I still remember the first time I got this particular book because it has such gorgeous photos and I was just like, “Oh, I’m all ready to go out and find all of these bees that are really solitary, rare bees.”

I’m totally excited to look for them. And then I started realizing just how challenging it is. You know, these things are really small, and they move really fast, and you’re like, “Oh, I can get a great photo and I’ll just use the photo to do the ID.” It’s like I look back at my photo, I even have a macro lens for my phone. And it’s like, you can’t get anything to hold still long enough.

Can you give some examples, if you’re not going to know how to identify every bee or you’re not going to be amazing at it, what should I know to distinguish in this situation so I know that I am planting the right thing?

Aaron Anderson: One of the things that researchers do, because like you said, it’s so hard to identify bee on the wing or out in the field. and if you’re just kind of trying to get that broad overview, you can look at: honey bees, bumble bees, big bees, small bees, and then green bees, because those are all different, what are called morpho categories, these broad groupings that you can just kind of lump them in.

That’s a great way to get a sense. You’re like, “Okay, I’m only seeing honey bees on this. I can identify honey bees.” Their characteristics are pretty easy to distinguish from other bees if you look at some photos and familiarize yourself with that. Bumble bees are really easy because they’re big, they’re fuzzy. Most people are familiar with bumble bees.

Sarah Beck: Adorable.

Aaron Anderson: Exactly. You can look at green bees. They’re in different groups across the bee world, but they’re easy to pick out because they’re shiny, metallic green. So that’s something you can quickly note.

And then look for small bees. You have to kind of familiarize yourself with what bees look like and trying to differentiate between them and wasps. Wasps have that really narrow waist. They kind of dangle their legs when they fly. But if you get comfortable you know, telling those different insects apart.

If you look for little bees, those are the types of things that you wouldn’t notice on a first pass just glancing at your flowers, you really have to sit there for a few minutes and see, “Hey, there’s these one-millimeter-long bees or these bees that are the size of a grain of rice that are going in and out of my flowers.” Hey, this plant is getting bumble bees, this one’s getting bees from across those different groups.

And then if you want to go a level deeper you can familiarize yourself with, you know, some of those main bee families. And then you can kind of say, okay, there’s these different groups within them. And again different books. The Bees in Your Backyard is a great one that kind of has these great photos and breaks down those groups.

You can start seeing some characteristics that are unique to some other groups of bees, like longhorn bees, where the males have these really long antenna and then the females are fuzzy and they kind of have these what almost look like chaps on their legs where they would pack the pollen in.

As you become more familiar with bees, you’ll be able to start noting these different characteristics more and become more familiar with them.

You can see totally different bees sometimes, more of some one year than other years. That is, to give a quick bee conservation plug, a great reason to plant a diversity of flowering native plants because you won’t necessarily have the same bees at the same population level each year. Different bees will prefer different types of flowers, especially depending on when they’re flying. Since, as Steve notes in his book there’s some that are only out there flying and foraging for a couple weeks. So if they emerge and if there’s nothing growing there, for them to get food and resources from, then they’re kind of out of luck or they’ll have to go onto a different yard.

Sarah Beck: That really stresses me out. But it sounds like what you’re saying is also that, you know, if you’re planting a set of plants that you think may be very attractive to some solitary or native bees, maybe don’t get discouraged if the first season or two that you have those plants, if they’re not suddenly attracitng bees you’ve never seen before, because it may take a few years.

What do you wish we knew about this? What do you think the concentration should be on, knowing that not everyone is going into your field?

Aaron Anderson: I think that a big question that I still have—with the wide variety of flowering plants that are out there and that you do see bees utilize—is I think a better understanding of the quality of some of those plants for bees because just because a bee is visiting and utilizing a plant and collecting pollen from it, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s an optimal resource. Maybe it’s the only thing that’s out there.

Something that’s mentioned a lot is dandelions in your lawn, they can be used as an early-season resource by bees, which is true.

Sarah Beck: They’re like, “This isn’t very good. If I had something better at the bar right now, I would totally be drinking it.

Aaron Anderson: “This isn’t the best, yeah. I wouldn’t be ordering dandelion.”

I think that it would be a big undertaking, but a better sense of that whole picture for a lot of the different plants that are in our urban areas, then it would kind of give a better sense of, okay, this is the quality of the habitat that you’re providing.

I think something else that would be really interesting to know about is also the impact that a lot of the chemicals that we find in urban areas have on bees at all different life stages. This includes pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, but then also some of the other contaminants that you can find in our residential areas because we have so much else going on. It’s not just pollinator habitat, unfortunately. We also have things running off and washing off surfaces, and I think a better understanding of how some of those substances and those chemicals impact bees not only as adults, but also in their developmental stages as larvae. I think that would give us a better understanding of what we need to try to prevent, but then also how we can mitigate it.

One thing that sometimes people are concerned about again, in our residential spaces, is creating what’s called an ecological trap, right? Where you’re creating this habitat, but it’s actually damaging. So you’re drawing pollinators into a floral display that then is hit by an insecticide.

Sarah Beck: Now we’re talking about a horror movie.

Aaron Anderson: Right, no, that’s a horror movie. I’m sorry to bring up that terrible visual. I think that that’s one of those things when you’re thinking about creating habitat in some of these areas is a better understanding of the risks that surround them.

Sarah Beck: Aaron, it was so fun talking to you.

Aaron Anderson: Yeah, it was great to chat with you too, Sarah. This was great.

Resources

Steve Buchmann’s new book, What a Bee Knows: Exploring the Thoughts, Memories, and Personalities of Bees, is now available through Island Press. More information available on his website.

For more information on planting for pollinators, see the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, and the Xerces Society.

This conversation mentions Buchmann’s buzz pollination research.

Watch here for the bee soccer videos out of Queen Mary University of London.

Chittka, Lars. 2022. The Mind of a Bee. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wilson, Joseph S. and Olivia Messinger Carril. 2015. The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Responses