Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Growing for Biodiversity

Spring 2023

What is biodiversity?

Exploring biodiversity in gardens seems simple at first glance. Many of us define it in relatively simple terms—how many species of plants? Birds? Insects? Our gardens are relatively small ecosystems, but if we consider the possible number of interactions in even a small urban garden, it is immediately evident that biodiversity is almost unimaginably complex. Why does biodiversity matter, and how is it measured? Here I connect with three scientists in our region to talk about their work on biodiversity.

Biodiversity in Urban Gardens is a multifaceted project that explores ecosystem dynamics in gardens along the California Central Coast. Dr. Stacy Philpott at UC Santa Cruz leads the research along with co-project directors Dr. Heidi Liere at Seattle University, Dr. Shalene Jha at the University of Texas at Austin, and Dr. Brenda Lin at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia. They conduct research on biodiversity in almost 30 urban community gardens in California.

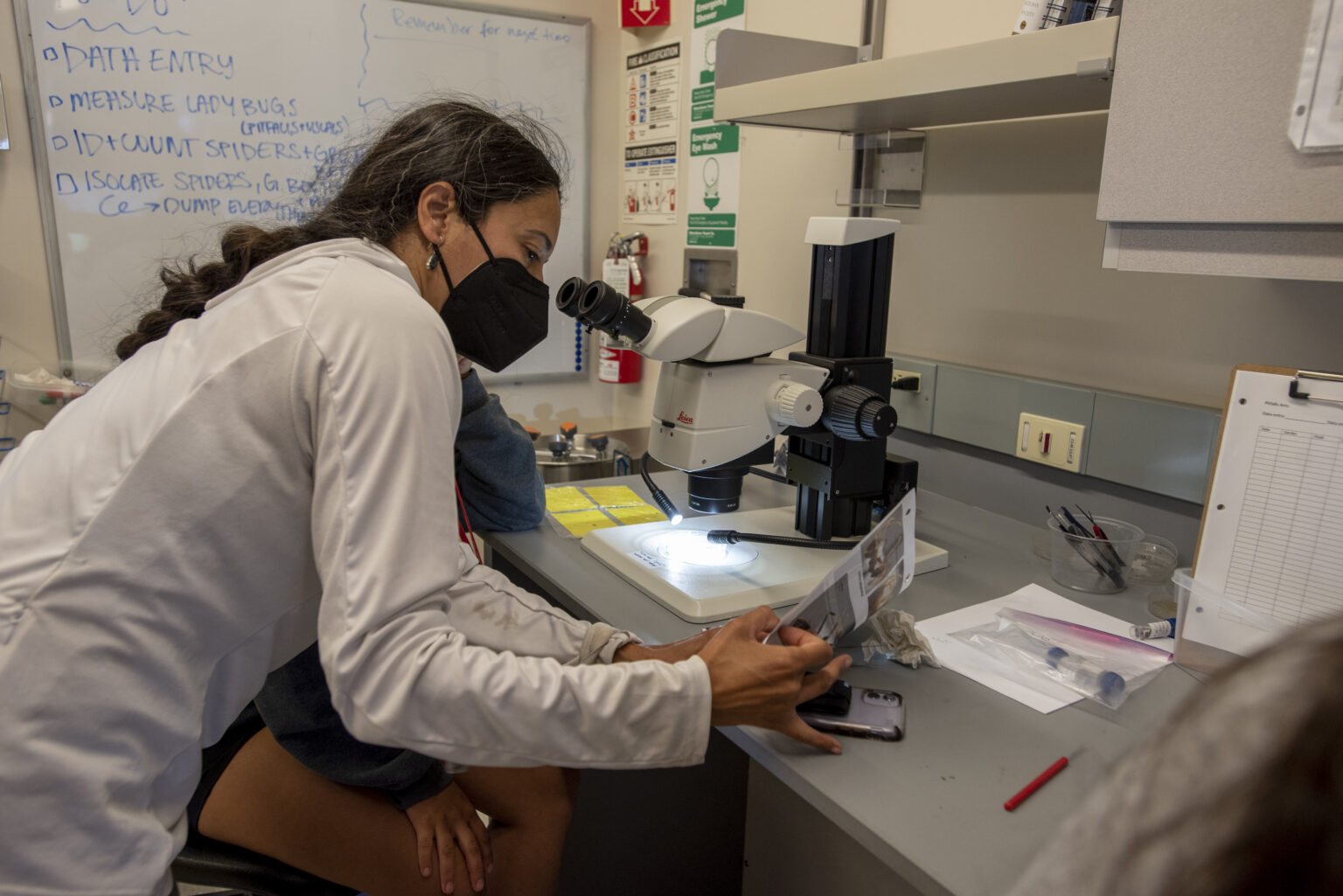

We talked with Liere about this project and a companion project she is conducting in the Seattle region. “In both regions, we are now focusing not only on the biodiversity, but on the functional traits: how the traits of the plants are affecting the different functional traits of the beneficial insects. For example, for spiders: are there small spiders, medium spiders, big spiders; what’s their hunting mode? What is their reproduction mode? How is this affected by the different plants, and by the composition of the landscape around the gardens?”

Increasing the number of species of plants (especially native) increases the number of species of insects and birds in our gardens. Having a diversity of species in a functional ecological group (for example, organisms that prey on or parasitize aphids) ensures that if we lose one to disease, weather, or other calamity, there will be others that can take its place. That leads to resiliency in the landscape—the ability of our garden ecosystem to bounce back following a disturbance. Evaluating the ecology of the garden is complicated by the fact that there is a lot of overlap in functional groups. An organism may be a predator as larvae and pollinator as adults, as is the case of hover flies, or be an herbivore as larvae and pollinator as adults, as is the case of moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera).

Biodiversity includes quantifiable metrics such as species richness—the number of species present, and abundance—the number of individuals present in each species. The identity of the organism is also important, as is its role in the system, and how much impact it has. Keystone species have an outsized impact on the ecosystem; oaks are a common example. In addition, biodiversity is studied at all levels—genetic, species, and ecosystem. Generally speaking, here we are addressing garden ecosystem biodiversity.

Scott Logan is the co-owner of Wild Wings Ecology, a company connecting people with nature in Los Angeles, and the Gottlieb Native Garden’s long-time naturalist. “Susan [Gottlieb] began the garden over 30 years ago,” he said. “She began in the westernmost part of the property. As time has gone on, she’s planted to the east. So it’s been a gradation of planting until the most recent planting was just last year on the easternmost part of this garden. From the oldest part of the garden to the newest part of the garden, I can visually see a greater variety of species, the different complexities of the ecosystem.” What makes a garden such as the Gottlieb Native Garden so valuable is that there are long-term records: weather, plants, phenology of both plants and animals—all kinds of measurements are taking place.

Research in the Pacific Region

Dr. Denise Knapp is the director of conservation and research at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, where she oversees a broad range of ecological research, including 22 staff working on over 60 projects, many applicable to garden biodiversity. Four scientists are focused on insects and other arthropods and their plant interactions—an unusual focus for a botanic garden.

“A big initiative we are planning is transforming public landscapes across a constellation of sites in Santa Barbara County to native plants,” Knapp tells me. We’re doing this in an experimental way by studying the plants, bugs and birds before the transformation and comparing to a control site as well. Involving the community in the transformation is an important part of this project – including studying who colonizes. We are really trying to link the plants to the birds with insects in between – pollinators, Lepidoptera larvae, pest control, and more.”

“We’ve been trying to figure out how vegetation diversity in the garden affects insect diversity and ecosystem functions such as pollination, pest control, and carbon sequestration,” Liere said. “One of the questions that we’re asking is ‘are there trade-offs and synergies within different ecosystem services in the garden?’ In agriculture often you hear that either you protect biodiversity or you produce food, and there’s a trade-off. We were wondering if that’s the same case in urban ecosystems. We’ve been finding more synergies than trade-offs. Growing food doesn’t have to lead to loss of biodiversity.”

These studies, the first of their kind, demonstrate that gardens can produce food and well-being benefits for humans as well as promote both plant and animal biodiversity.

“We are also trying to understand what are the factors both at the local management level—what gardeners are doing inside their garden—and at the landscape level—what is the composition of different land uses around the gardens that affect the communities of insects and the ecosystem services that they provide,” said Liere.

In the Gottlieb Native Garden, Logan has many roles. One is to oversee the university studies that take place in the garden, including research on hummingbirds, bats, and native bees. He often uses BugGuide for identifications, and is a big fan of iNaturalist. “What I’ve learned about iNaturalist is that there are biologists perusing what’s being posted if it’s in their interest. And through that I’ve connected with many biologists. With the help of their expertise, in this garden I’ve found four new species of insects, and three other insects that have never been recorded in North America. As well as many, many, many insects that have not been recorded in California.”

Measures and Analyses

Scientists have devised many ways to measure and analyze biodiversity beyond simply counting species, and are making good use of advances in computer technology that contribute to our ability to better understand our environment. Some methods of measuring are simple, but incredibly informative. Many community science projects employ methods any gardener can learn. In addition to projects on iNaturalist, the Xerces Society has several relatively simple protocols that are used by scientists around the West.

“We use a variety of methods to quantify insects. Often we use a modified Xerces protocol, where we’re identifying organisms on the wing to the finest degree that we can along a transect – we’re trying to catch as few things as possible, both so that we can avoid killing insects and to keep the work in the lab to a manageable level. We capture representative individuals so we can identify them more accurately though,” Knapp says. “We have a pilot for the landscape transformations project that we’ve been monitoring for two years, a private yard that is being converted from exotic to native.” In addition to pollinator transects, the team is using two other methods at that site; point counts for birds, and beat sheeting an array of plants for arthropods. The yard is undergoing transformation now, and the team will continue to monitor plant, bug, and bird diversity for several more years.

Liere said one method used in their studies is to put out sentinel prey to estimate pest control services. “You choose eggs of certain herbivores, or just caterpillars, and put them out for 24 hours and then see what the predation percentage is. But we’ve always wondered who comes when we go. So we started doing videos last summer to figure out the identity of those predators that have taken away the sentinel pest. We’re still analyzing them.”

At the Gottlieb Garden, monitoring for species richness is ongoing for many insects, birds, and mammals. Logan notes that there have been a few native bee studies conducted by universities—which plants the bees favor, for example.

“My native bees monitoring has been extensive; I’m at now 52 species of bees in the garden, 48 of them native,” he said.

Among other sites, the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden will be renovating the butterfly garden at Alice Keck Park in Santa Barbara to be native dominated, and investigating the differences between Lepidoptera use of native and non-native plants before vs. after the transformation. They will use some of Doug Tallamy’s methods to assess Lepidoptera, both caterpillars and adults.

New analytic methods are contributing to understanding the data. “We have the benefit of better statistics now, multifaceted, multivariate statistics where we can measure the different variables and try to pull apart what matters,” Knapp said. “We also use high-definition images of our specimens from multiple angles, together with online tools such as iNaturalist and BugGuide.net, to get identification help from experts. This has the wonderful side benefit of creating a digital biodiversity library that can be used for education and outreach as well as science.”

What Can We Do?

Joining iNaturalist can transform our relationship to gardens. Along with its app, Seek, it is an ideal way to seek out identifications of insects and birds we photograph, and may contribute to scientific knowledge of our environment. In San Diego, gardener Bonnie Nickel has contributed over 4,000 observations. Some of the iNaturalist projects that include her observations are Bees of San Diego, Butterflies of San Diego, Flora of Anza-Borrego, San Diego County Plant Atlas, and Global Pollinator Watch. “I use it every day, and every day it inspires me to learn more about the interactions between native California plants and the insects that rely on them. Discovering the iNaturalist app has literally changed my life!” Nickel said.

We can all promote biodiversity in our gardens and in our communities. We are fortunate that gardens have many factors that promote biodiversity: garden age, cultivation of perennial systems and corresponding lack of disturbance, complexity in space and time, niches, edges, sources of water, food, shelter, and places to nest. Plan for a long season of bloom. Protect the garden from excessive wind (small flying things don’t like windy sites). Practice no-till methods. When possible, leave leaf litter in place. Layer plants, from grasses and forbs to perennials, up to shrubs, vines, and trees. Provide some thorny plants to protect nesting birds. Create microenvironments—a sunny patch of soil for solitary nesting bees, a moist shady spot at the base of a rock, leaf litter under native plants. Always provide a source of water.

One thing scientists agree on is that even a few native plants can make a difference. Keep in mind that we don’t notice that which we cannot see! For instance, while lavender certainly attracts many species of bees, butterflies, and other insects, there are almost certainly species that are absent if their preferred native plants aren’t available.

So plant your lavender, but also include native plants in your garden. Choose native plants that provide beauty for the gardener.

At the Gottlieb Native Garden, Logan said, “Susan’s message is always just plant a plant. Don’t be intimidated and don’t think, oh, I have to tear up my entire yard. Just plant a plant, plant a couple plants, see how it goes!”

Read the first article; Voices of the West; New Science on Life in the Garden

Did you know that oaks can harbor over 800 species of insects? That includes only those feeding directly on oak, where they feed on every part: bark, leaves, roots, flowers, seeds, and even between the layers of leaves. We don’t usually notice these insects, but we frequently spot the birds that feed on them. In addition to birds, spiders, and other arthropods, lizards, mammals, fungi, and many other organisms rely on oak-feeding insects for their own survival. >>Read More

Read the latest article; Voices of the West; New Science on Life in the Garden: Native Plants

As a gardener, I want it all—a thriving habitat full of native plants designed to attract wildlife, plants that evoke childhood memories, fragrant blossoms, intriguing foliage, delicious treats, and beautiful, inviting spaces for hanging out. Surprisingly, delving into the recent science on native plants for insects and other wildlife has inspired me to add more non-native lavender (Lavandula spp. and cvs.) to my garden. >> Read More

Resources

As we explore in the months ahead, we will learn about research being conducted on native plants, the wildland-urban interface, soil ecology, the impact of changing climate, and many more topics related to the food web. As I introduce new scientists and include further research and insights, these resources will include a link to all our Voices of the West experts.

University of Texas at Austin. 2023. “How urban gardens are good for ecosystems and humans.” Phys.org. Feb 7, 2023.

Resources from first article

Tallamy, Douglas W. 2020. Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. Portland: Timber Press.

Tallamy, Douglas W. 2021. Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees. Portland: Timber Press.

Pavlik, Bruce M., Pamela C. Muick, Sharon G. Johnson, and Marjorie Popper. 1993. Oaks of California. Los Olivos: Cachuma Press.

Gottlieb Native Garden Hummingbird Banding Project

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden; Restoring Habitats – Building Ecological Resilience

Responses